Housing financialisation | What is it and why is it of our concern ?

Summary:

Why do rents and property values increase? Is it just because of the touristification and/ or gentrification or because the housing market is of particular interest for investors? What is the role of the state and how do policies affect housing? This -extensive- article will provide with some answers regarding the unaffordable rents and the difficulties households face regarding covering their housing needs, by looking into the housing financialisation theory. We will start by reviewing the international literature, and then focus on the Greek case, as outlined by the debt crisis and austerity policies linked to land and housing dispossession.

What is housing financialization

Housing financialisation is a term that describes the policies and practices that promote the perception of housing as yet another investment product 1. The Greek translation of the term (χρηματιστικοποίηση) points towards a monetary cognitive 2. Yet, the process of financialisation is more about the dynamics that transform housing into a kind of capital 3 that produces value and renders profit, rather than as money values per se. The aim of this article is to seek the historical, political and economic factors that have deconstructed the concept of housing as a social good or a human right and have normalised speculative real-estate practices, also apparent in Athens in the form of irrational increases in rents and inhabitants’ displacement pressures.

Scientific discourse on housing financialisation gained more grounds in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2007, by shedding light on the practices of housing dispossession by vulture vestment funds and capital investment companies (henceforth “funds”), many researchers reckon that the roots of this process are better traced in the commodification of housing, as well as the policies that promoted homeowership 4.

At this point, it is worth mentioning that even though Greece followed a different pathway of urban development than European counterparts, in many countries social housing has been for many years a popular and dominant housing model. Many residential units that were built by State support, managed by municipal or regional authorities, with a basic scope to provide housing in low, social rents 5. This housing model was a solution to housing problems faced after War World II, especially for vulnerable social groups. Ideologically, this was based on the perception that housing is a social good, part and parcel with other welfare policies.

Scandinavian countries and especially Sweden, adopting a more progressive understanding that housing is a human right, tendered this housing model also for the middle-class households. Therefore, a framework was set where municipal housing competes with the private sector, and is keen on maintaining rents lower than those offered by the free market.

Pathways to homeowernship

With the dominance of neoliberalism since the ‘70s, welfare services were considered as too costly, and social policies shifted to promote the market’s interests. Regarding housing, two chief trends were observed: the privatisation of social housing and the promotion of homeownership. The supply and demand for homeownership were equally boosted by numerous spatial, urban planning and economic policies. In many countries, planning rules and building regulation modifications where accompanied by policies that granted for free public land to developers so that residential properties can be erected and then sold 6; while, at the same time, special incentives were provided for housing purchases, such as grants and subsidies.

Moreover, budget cuts for social welfare and disinvestments in social housing, promoted a perception that owner-occupied housing offers de facto a better quality of life 7. This was accompanied by deregulation and liberalisation of financial market, that allowed banks to offer mortgages and loans in favourable terms and conditions, even to social groups that were previously excluded from credit financing due to their low income revenues and high risk of insolvency. And while real economic factors such as wages and available net household income came to be stagnating 8, even more households ended up in singing into debt to cover basic needs such as housing, healthcare, education and retirement 9. The percentage of home ownership kept increasing until the financial crisis broke out, but let us briefly keep in mind that this increase wass quite fictitious, since properties are technically owned by the creditors until the mortgage is paid in full.

The global crisis of 2008 and its aftermath

When a mortgage is signed, the capital representing the value of loan is released. This form of capital it can move freely in the market, in comparison to when it is fixed as value in the building of the property 10. Hence capital is free to return to the stock market, and be re-invested in other financial products acquiring the form of bonds, stocks and securities. Hence, a mortgage can be separated, mixed with other investment products, transform into a new title that can be resold in the stock market as a new product, in other words it can be securitised. So, with the mediation of the credit markets, housing can produce capital liquidity, despite its spatial fixity 11. A key prerequisite for the above, is that the mortgage is serviced, that is to say that the debtor deposits part of her/his salary on a monthly basis in order to pay the mortgage. When capital fictitious transactions do not correspond to the real values produced, then a crisis is underway 12.

Maybe the causes the causes of the financial crisis can be traced somewhere here. Many households, especially in the US, Spain and Ireland were forced, convinced or coerced to sign mortgages that were then exchanged as bonds and titles in the stock market. When mortgages stopped being serviced, the stock market dragged the economy in the avalanche of what was called the financial crisis, property values plummeted and people’s homes and lives were put at risk. And since borrowers failed to service their mortgages due to austerity restructuring, salary cuts and/ or unemployment, their loans turned into non-performing loans (NPL).

It should be noted that banks’ aim is not to engage with real-estate, but rather with money and capital markets.

Therefore, the rapid increase of NPLs negatively affected banks’ balance sheets. The solution prevailed, particularly in the US, Spain and Ireland, was to sell NPLs to funds, so that banks’ financial status could be consolidated with lower NPLs exposures. Funds were the only players in the market with financial power and available monetary capital willing to invest in real estate market by buying NPL packages, or foreclosed properties in bargain prices – for example property values in Spain, just like in Greece, had decreased by 40% 13. At the same time, local governments moved on with selling social housing to financial investors for peanuts. But when funds got hold of the ownership of properties, they preferred that previous “mortgaged” owners or tenants were forced out, so that properties could be managed according to the business plan.

The funds’ speculative games involving houses

The funds’ initial approach to the housing market was speculative, following the real- estate mantra “buy low, (re) sell high”. On a macroeconomic perspective, the situation is as follows: (i) since 2009, interest rates for mortgages are extremely low (approximately 1%) and (ii) since 2015, the EU decides to proceed with quantitative easing, meaning that the Central Bank buys government bonds in order to inject more money in the markets. Eventually, investments in real estate started to offer higher profits and yields than investments in financial products such as stocks, government bonds and shares. Gradually, the way that funds approached the housing market changed and their strategy developed into a mid-term one . They set up subsidiaries, taking the legal form of real estate investment trusts- REITs, so that they can rent out in the private market the properties they are managing.

Meanwhile, the legislation regarding REITs changed in many countries, offering favourable conditions for international investors, such as zero taxes over profits or the ability to choose a different country as that of tax residence 14. At the same time, the banks set stricter criteria for mortgages, so access to mortgages becomes even harder for most households, who subsequently resort to renting a house in the private market. In addition, legal changes regarding tenancy agreements set tighter criteria regarding the duration of the leases and tenants’ rights 15.

As explained by Haila (2016), real-estate actors and especially investment funds that aim to deliver dividends to shareholders, develop strategies that focus on maximising rent revenues, that is to say that they develop a rent maximising behaviour. This can be achieved through different strategies such as building renovations that justify rent increases 16, unjustifiably increase the rent without any improvement of the building stock 17, investing in areas with gentrification potential, where a rent gap is developed and the rents paid by gentrifier uses and users are higher 18 or through reinvesting profits in capital markets 19. Moreover, lower operational costs achieved through investments in technological developments and in platforms allow funds to bypass intermediaries and further increase profits.

These activities influence other investors in the real-estate market, such as property owners and local real-estate companies. According to Haila (2016), property owners and small investors tend to develop rather irrational behaviour regarding their own properties, out of belief that house price values can only increase or that their property is “the best in the market”. Moreover, by considering that that information is hidden by the big market players, small property owners tend to impose even higher rent increases 20. These speculative behaviours have as a direct effect the increase in rents and housing costs in ways that households face significant financial pressures, since they have to dispose a greater percentage of monthly income for covering their housing needs (housing affordability). Therefore, households that can no longer afford to pay rent, they are forced out of their homes and seek for more affordable options in different areas or in the periphery of the city, while they are replaced by wealthier tenants. And as the social composition in neighbourhoods changes, cities and their citizens transform into capital flows that serve funds’ and other real-estate owners’ financial interests.

What’s the case in Greece?

Considering the above, we drive attention to the housing power relations in Greece, and particularly in Athens, to assess the specificities of housing financialisation. Looking at the way homeownership was promoted in Greece through informal settlements and the “antiparochi” system 21, it is suffice to claim that mortgage credit and finance capital did not play a major role in the promotion of homeownership or housing constriction, in contrast to international case studies 22. “Antiparochi” developed as a specific housing policy that provided most social groups with access to homeownership, accommodating accordingly the income restrictions of households. Moreover, it limited -or even eliminated- public expediture costs the State would have to bear in the case of investments in social housing provision 23. The institution charged with managing the housing needs of the most vulnerable was the (Greek) Workers’ Housing Organisation (in Greek OEK)24 that secured homeownership in housing stock the OEK planned and constructed, or subsidised rent, rather than renting out housing in affordable rents as was the case in other countries.

Moreover, due to Greece’s particular macroeconomic conditions prior to joining the Eurozone, such as inflationary pressures, -constant- currency devaluations, high unemployment rates and the political instability, banks offered mortgages at high interest rates (25%), that were restrictive for the majority of the population. However, given the absence of concrete housing policies, in the Greek society, the perception that homeownership guarantees at least a “roof above the head” as refuge against financial instability was widespread. Therefore, private savings, family support (in the form of money, dowry or inheritance) 25 or the sale of property and/or land at the place of origin were mobilised so that households could purchase a flat in Athens 26. Hence, contrary to the international paradigms that analyse homeownership as mediated by credit, in Greece it was a case of purchase and sale in present time, with no future obligations bound by interest rates.

However, when Greece joined the Eurozone, the financial and economic condition changed. The country’s credibility was perceived as equal to the one of Germany and France and credit institutions offered gallantly credit to local banks. Interest rates for mortgages adjusted to the European average of 5% and Greek banks started to compete with each other in offering mortgages and consumer loans 27. According to Toussaint (2017), in only one decade, mortgages in Greece rose from 5.8% of the country’s GDP in 1999 to 33.9% in 2009. After observing the rising indebtedness, legislators moved quickly by establishing in 2010 the 3869/2010 Law (known as the “Katseli Law”) on household insolvency. This Law determines the conditions for debt negotiation and servicing, specially foreseeing that creditors are not allowed any claims on primary residence, that is to say that primary homes stay intact beyond debt negotiations 28. In other words, this framework establishes a regime of protection of primary residences, hence the home of indebted household cannot be negotiated or repossessed by creditors.

Non-performing loans and insolvent households

The global financial crisis in Greece takes the form of a debt crisis and political powers prioritise banks’ bail outs. Meanwhile, severe austerity measures target labour rights, shrink wages and pensions, while public enterprises and state properties are sold to foreign private capital. At the same time, the taxation imposed on households is odious. In addition to indirect taxes imposed on fuel, electricity and essential goods, income tax rates increase, while property is subjected to additional taxation through the Uniform Real Estate Property Tax (ENFIA). And while GDP decreases by 20%, real wages further decrease by 40% 29.

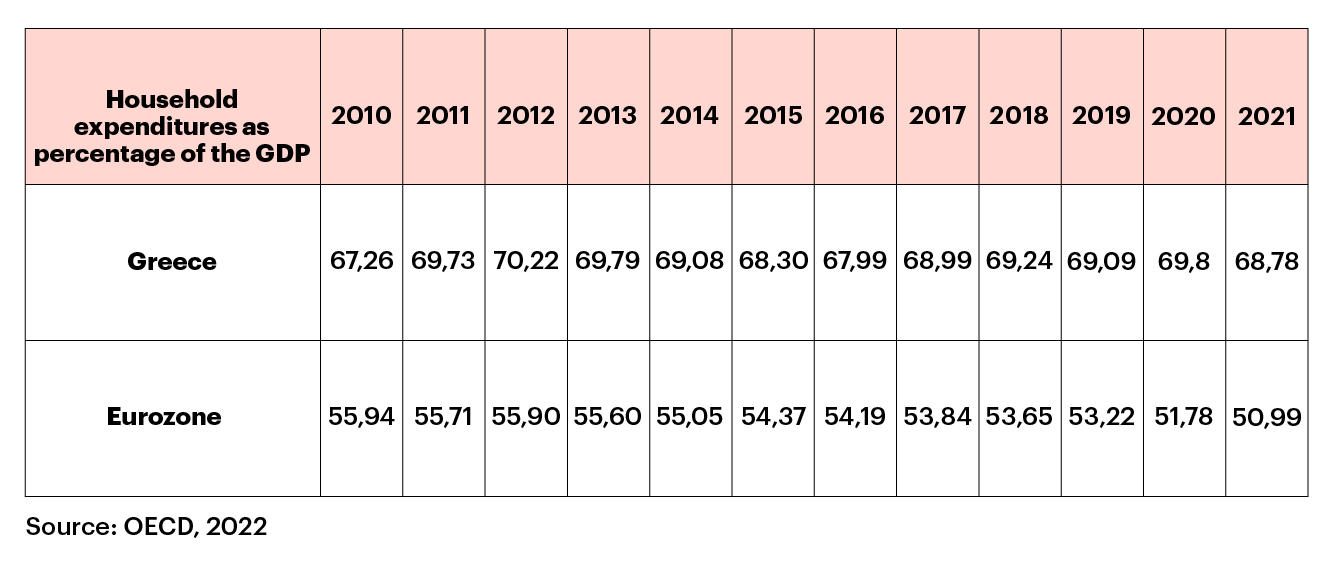

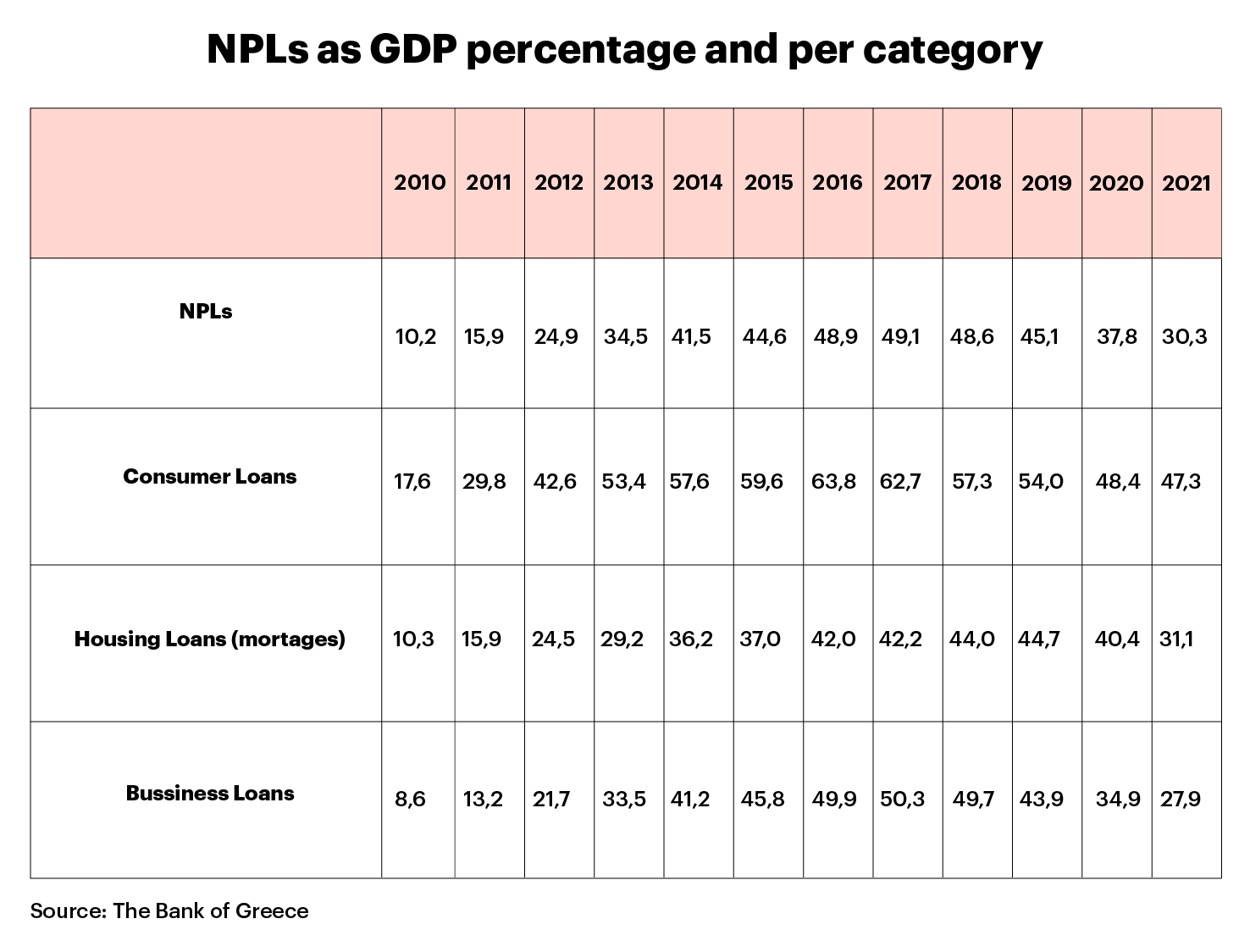

According to Matsanganis et al. (2018) this additional decline in wages is due to odious taxation. Many households are increasingly unable to pay back debt obligations, beyond tax and social security contributions. As household expenditure as a share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increases, households start to use savings or accumulate debt. This situation translates in the banks’ books as an increase in non-performing loans (NPLs) 30.

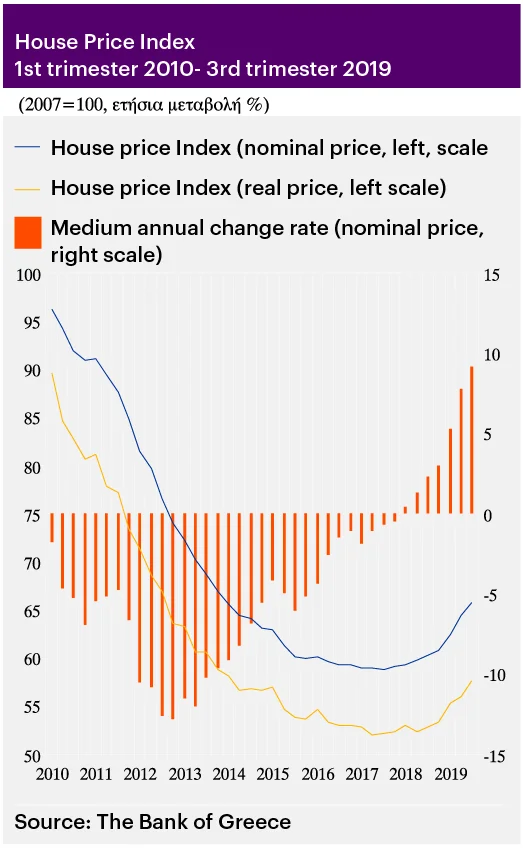

From 2010, real estate values decrease and plummet in 2016. In comparison to pre-crisis levels, house prices loose 40% of their value 31. Real-estate sales freeze as domestic and foreign demand is almost nil. International rating agencies such as Moody’s and Fitch downgrade Greek bonds to junk, alarming investors that Greece is at the verge of default 32.

The banking sector – “Defensive Stance”

The macroeconomic situation is bleak. Banks and austerity governments are unable to deal with the accumulating rates of public and private debt. The only existing legal framework on insolvency is that of the Katselis law, which proves beneficial both for households, as homes are not challenged by repossessions, and for creditors, who, instead of losing the capital lent, they benefit from debt negotiations 33.

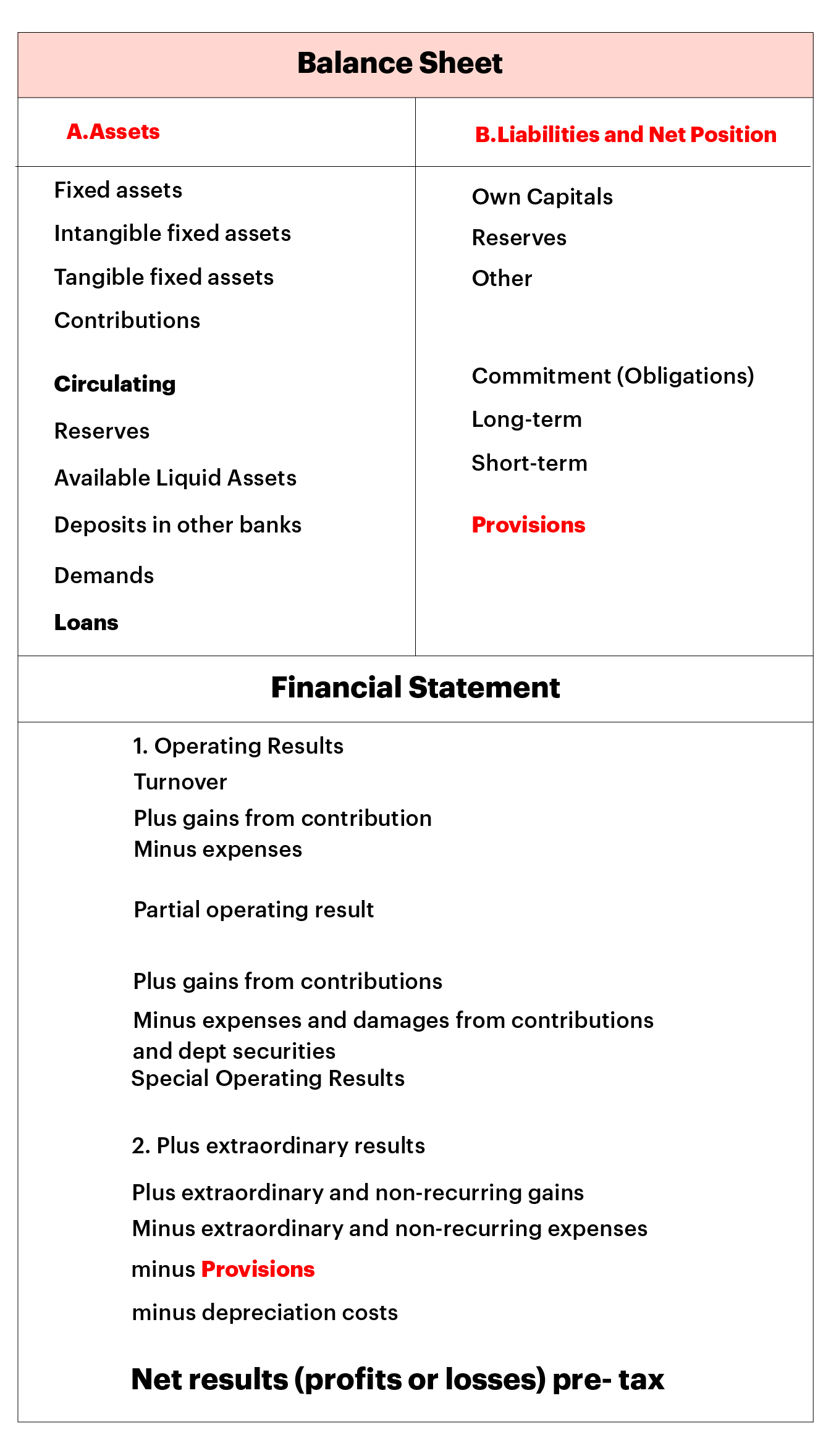

Moreover, banks, as credit institutions, are obliged to present operational financial statements in their balance sheets. However, they face a particular issue concerning the accounting size of loan provisions 34. Provisions as a value reflect the probability of recovery or loss of a borrowed amount. For each loan, banks are required to record on the assets side of their balance sheet the amount of the loan granted, and on the liabilities side, the estimated provisions for that loan 35. At the end of the tax year, the total amount of provisions is transferred as an expense to the profit and loss account, and deducted from the estimated profits. When the loans are non-performing, provisions increase. Then the financial result of activities is calculated as a loss, posing the question of bankruptcy and recapitalisation 36.

Until 2016, banks, under Katselis law, collaborated in debt negotiations with borrowers. Any kind of out-of-court settlement was considered as preferable, as this allowed debt to be presented as perfoming in spread sheets, thus maintaining the values of provisions low 37. Additionally, new products were promoted that considered part of debt as frozen, and part as servicing. In many cases banks accepted a minimum possible servicing, e.g. €100 in place of a €600 mortgage instalment 38, as long as this would allow them to present loans as performing.

At the same time, foreclosures of homes were systematically avoided, as auctions would provoke further decreases in the already plummeted property values 39, thus they would further jeopardise book values, as the amount of provisions would be higher 40. The European Central Bank allowed Greek banks to participate as bidders in foreclosures, so that property values are maintained, while up to 2017, successive laws foresaw freezing of foreclosures 41.

Such political fears over the potential collapse of the banking system may explain why governments, whatsoever their ideological orientation, avoided any securitisation of non-performing loans and insisted on maintaining the Katselis law (beyond successive amendments in the criteria for primary residence protection), despite pressures from Institutions 42 43. The offers made for the acquisition of non-performing loans by funds were that low, that would force banks to record higher provisions, and jeopardise balance sheets; a scenario not palatable for both the government and bank directors 44. So, until the late 2010s, the protection of the primary residence was preserved as foreclosures and securitisation would negatively affect the viability of local credit institutions, beyond the potential social outcry and political upheavals 45.

The Greek banks – “Extroversion era”

By 2017, the political and economic conditions in Greece change. The country exits the memorandums and the “danger” of Gr-exit under a left wing government is by-passed. Rating agencies restore assessments on Greece’s credibility, placing it into positive ranking, and the low prices in the real estate market are recognised by perceived by investors as “opportunity” 46.

By 2016, house prices in Athens were estimated at € 1,470 per square metre (sq. m.), while in other Southern European capitals prices were particularly high. For example, in Madrid prices reached at € 4,127 per sq. m. and Lisbon at € 3,117 per sq. m. 47. While for some Greek households property sales is considered as a way out of debt burdens 48, foreign and Greek investors start buying housing real-estate because of the profitability margins created when the assets are placed in the market as short-term leases 49. After all, Athens is transformed into a city break destination and short-term rentals through the Airbnb platform guarantee high capital returns 50.

Other initiatives, such as the Golden Visa program attract the interest of financiers. More precisely, Golden Visas provide a 5 year residence permit to third country nationals who invest over €250.000 in Greek real-estate. This especially captured the interest of Chinese entrepreneurs who purchase more than one assets for a total amount of €250.000, and then resell each asset for €250.000 to compatriots, driving house prices up 51. Additionally, “family funds”, i.e. foreign investors managing capital up to € 10 bn, are active in real-estate affairs in Athens. These funds seek to purchase entire buildings in central areas and change their uses into into touristic uses (hotels, apart-hotels) or lease them for mid-term use to international highly/paid employees, digital nomads or artists 52. The rent requested is significantly higher than long-term/ permanent tenancy leases.

These activities influence landlords and smaller property owners who decide to pursue higher profits by placing their assets as short-term rental entries and evicting previous tenants 53. Additionally, households in debt negotiations prefer to sell their mortgaged assets to international investors and settle debt. This way they become debt-free, but also home-less 54. And as these real-estate activities lead to increases in property values, the risk of a high number of provisions in banks’ spread sheets declines 55.

As property values are recovering, banks are in a position to sell off mortgaged properties that burden their budgets, without recording losses or a high number of provisions, but profits. They redefine their stance in debt negotiations: if the debt is small and the property is located in a “prime” area, property ownership will be challenged 56. From 2017 onwards a new law established online auctions for foreclosures, so that auctions can be handled at a fast pace, while any social mobilisation opposing to housing repossessions can be eluded. According to the analysis by Kiki and Trompoukis (2021), from 2017 till 2020, 38% of the carried-out auctions were dealing with residential properties, 10% of which locates in the city centre of Athens. It is interesting to note that banks have now started to sell those repossessed properties as Real Estate Owned properties (REO) mainly to foreign investors in Athens and Thessaloniki, and Greeks in the rest of the country 57.

Finally, banks are obligated the Basel Accord to lower their NPLs exposure the end of 2021. Already by 2015, a framework launched, established the norms for debt management companies, the Servicers. According to Law 4354/2015, these companies are obliged to have their tax base in Greece, regardless of who participates as main capital shareholder, and main activity is to convert NPLs into performing by persuading debtors to service their obligations 58.

The end of primary residence protection

In 2019, a newly elected government inspired and dedicated to neoliberal reforms, approved two interconnected legal frameworks: (i) The abolishment of Katselis Law and its replacement by Law 4738/2020 (the “Second Chance Law”). Erasing a decade of austerity, this law equates the bankruptcy of individuals with the bankruptcy of traders and establishes procedures for primary residence liquidation for the settling of debt. While primary residence protection is wiped out, state support is tendered only in marginal cases (e.g. couples with an annual income of up to €10,200 and a house value of up to €120,000) through the “Bridge” program. According to this initiative, households in arrears can remain in their home as tenants, as ownership of the asset is transferred to a new public body supervised by the Ministry of Labour and Social Security 59. After 12 years they can reclaim ownership of the property if they are in position to pay off their debt. However, it should be considered that as time passes by, property values tend to rise; and if a household is not able to service the mortgage in present time, it is rather unlikely that they will be able to do so in 12 years, in a country with declining wages, benefits and jobs 60.

(ii) The establishment of the “Hercules” project, the first mortgage securitisation program, according to which NPLs are transferred to a special purpose vehicle (SPV) in Ireland. The SPV securitises the debt and goes on with selling it to foreign investors, while Servicers, i.e. the debt collection agencies, bare the task to persuade debtors to service their debt. It is worth noting that often the main shareholder of the funds that purchase NPLs portfolios coincides with the main shareholder of Servicers 61. And as mortgages and the property of homes change hands, foreclosures start to accelerate. So far, emphasis remains on avoiding evictions and converting mortgaged homeowners into tenants. This way NPLs can be classified as performing, provisions can remain low, and property values high. There lies why housing repossessions in Greece are not illustrated, until now, with the violent images of evictions as per Spain and Ireland.As provisions are still high, carrying the potential to harm property values and lead to default, properties are dispossessed, but the former owner-current tenant is maintained to service the and transform it into performing financial asset in banks’ balance sheets.

This schema pinpoints to specific power relations developed twofold by housing financialisation dynamics: (i) investments of small property owners and medium-sized funds that displace tenants, and (ii) capital investments by funds that transform the indebted owner into a tenant. In this context, any social outcry against housing dispossession is countered by arguments that people still enjoy “a roof over their heads”. It is worth asking until when. The answer probably lies in debt provisions, financial operations and the way debt can also become productive.

Finally, a personal note: lately, many local and regional governments in the European Union are investing in social housing through inclusionary planning projects, and asset purchases that increase the affordable or social housing stock. This way they can intervene more effectively in the housing market and impede the housing pressures caused by soaring rents due to housing financialisation. I believe that the “Bridge” programme could serve as a basis for restoring social housing provision in Greece, if the ownership of repossessed properties remains within the state, housing is secured for vulnerable groups, and the stock acquired is used to intervene in the housing market and regulate house prices and rents in Athens. However, this remains a question of a careful reading of the socio-spatial pressures caused by housing financialisation, of ideological orientation, and, above all, of political will.

I’d like to thank Danai Maragkoudaki and Alkis Kafetzis for our excellent collaboration and especially for their support and patience.

This research was funded by the European Commission, through the Horizon 2020 Excellent Science program, H2020 Marie Skłodowska- Curie Actions (Grant Agreement 795611).

Download PDF

English References:

- Aalbers, Manuel, “Financial geography II: Financial geographies of housing and real estate”. Progress in Human Geography, no. 43(2019): 376-387.

- Aalbers, Manuel. “The financialization of housing: A political economy approach” Routledge: London, 2016.

- Adkins, Lisa, Cooper, Melissa, and Konings, Martin. “The asset economy”. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2020.

- Alexandri, Georgia. “Housing financialisation a la Griega”. Manuscript submitted for publication, 2022.

- Alexandri, Georgia and Janoschka, Michael. “Who loses and who wins in a housing crisis? Lessons from Spain and Greece for a nuanced understanding of dispossession”. Housing Policy Debate, no. 28 (2018): 117-134.

- Belotti, Emanouele and Arbaci, Sonia. “From right to good, and to asset: The state-led financialisation of the social rented housing in Italy”. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, no. 39 (2021): 4-433.

- Beswick, Joe, Alexandri, Georgia, Byrne, Michael, Vives-Miró, Sonia, Fields, Desire, Hodkinson, Stuart and Janoschka, Michael. “Speculating on London’s housing future: The rise of global corporate landlords in ‘post-crisis’ urban landscapes”. City, no. 20 (2016): 321-341.

- Christophers, Brett. “The state and financialization of public land in the United Kingdom”. Antipode, no 49 (2017) 1: 62-85.

- Coq‐Huelva, Daniel. “Urbanisation and financialisation in the context of a rescaling state: The case of Spain”. Antipode, no. 45 (2013): 1213-1231.

- Dagkouli-Kyriakoglou, Myrto. “The ongoing role of family in the provision of housing in Greece during the Greek crisis”. Critical housing analysis, no. 5(2018): 35-45.

- Emmanuel, Dimitris. “The Greek system of home ownership and the post-2008 crisis in Athens”. Région et Développement, no. 39 (2014): 167-182.

- Fields, D. “Unwilling subjects of financialization”. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, no. 41(2017): 588-603.

- Forrest, Ray and Hirayama, Yosuke. “The financialisation of the social project: Embedded liberalism, neoliberalism and home ownership”. Urban Studies, no. 52 (2015): 233-244.

- Gotham, Kevin. “Re-anchoring capital in disaster-devastated spaces: Financialisation and the Gulf Opportunity (GO) Zone programme”. Urban Studies, no. 53 (2016): 1362-1383.

- Gotham, Kevin. “Creating liquidity out of spatial fixity: The secondary circuit of capital and the subprime mortgage crisis”. International journal of urban and regional research, no. 33 (2009): 355-371.

- Gourzis, Konstantinos, Herod, Andrew, Chorianopoulos, Ioannis and Gialis, Stelios. “On the recursive relationship between gentrification and labour market precarisation: Evidence from two neighbourhoods in Athens, Greece”. Urban Studies, (2021) doi: p.00420980211031775.

- Haila, Anne. “Urban land rent: Singapore as a property state”. Malden, Oxford and West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, 2016.

- Harvey, David. “The Limits to capital”. London: Verso, 2018.

- Janoschka, Michael, Alexandri, Georgia, Ramos, Hernan and Vives-Miró, Sonia. “Tracing the socio-spatial logics of transnational landlords’ real estate investment: Blackstone in Madrid”. European Urban and Regional Studies, no. 27 (2020): 125-141.

- Kemeny, Jim. “Corporatism and housing regimes”. Housing, Theory and Society, no. 23 (2006): 1-18.

- García‐Lamarca, Melissa and Kaika, Maria. “‘Mortgaged lives’: the biopolitics of debt and housing financialisation”. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 41(2016): 313-327.

- Lapavitsas, Costas. “Profiting without producing: how finance exploits us all”. London: Verso Books, 2013.

- Matsagganis, M., Parma, A. and Karakitsios, A. Social mobility aspects in crisis Greece (2018).

retrieved on 15/11/2019. - OECD (2022), Household spending (indicator). doi: 10.1787/b5f46047-en (Accessed on 04 April 2022)

- Pettas, Dimitris, Avdikos, Vasilis, Iliopoulou, Eirini, & Karavasili, Ioanna. “Insurrection is not a spectacle: experiencing and contesting touristification in Exarcheia, Athens”. Urban Geography (2021): 1-23.

- Rolnik, Raquel. “Urban warfare: Housing under the empire of finance”. London: Verso Books, 2019.

- Rolnik, Raquel. “Late neoliberalism: The financialization of homeownership and housing rights”. International journal of urban and regional research, no. 37 (2013): 1058-1066.

- Siatisa, Dimitra. “Anyone at home? Housing in Greece, the impact of austerity and prospects”. Athens: Rosa Luxembourg Foundation, 2019.

- Smith, Neil. “The new urban frontier: Gentrification and the revanchist city”. Oxon and New York: Routledge, 1996.

Greek references:

- Kiki, Kelly and Troboukis, Thanasis, Residential property accounts for 38% of personal assets “lost” due to bank involvement up to day, 2021.

- Leontidou, Lila, “Cities of silence: Workers’ settlements in Athens and Piraeus, 1909-1940”. Athens: ETVA Cultural and Technological Foundation, 1989.

- Lialios, Giorgos. “Changes in property ownership in the Athens city centre during the financial crisis decade (2009-2018). The case of Exarchia”. Master’s thesis. National Technical University of Athens, School of Architecture.

- Mantouvalou, Maria and Mavridou, Maria. “Arbitrary building: one way street leading to a dead end”, Architects’ Association Bulletin, issue #5, (1993) 588-571

- Balabanidis Dimitris, Papatzani Eva, Pepas Dimitris “Airbnb in the city. Opportunity or threat?” Athens: Polis, 2021

- Balabanidis, Dimitris and Papatzani, Eva. “Airbnb and the future of housing in Greece”. 2022. (accessed on 10/4/2022)

- Polyzos, Giannis. “Reformers’ dreams and planning reforms”, in the catalogue of the exhibition titles “Athens in the 20th century”, Athens: Ministry of Culture, 1985

- Toussaint, Eric. “Public debt, its history and significance in today’s crisis”. Athens: Redmarks, 2017

- The Bank of Greece. Evolution of loans and non-performing loans, 2022 (accessed on 13/05/2022)

- The Bank of Greece. “Interim Report on Monetary Policy”. Athens: The Bank of Greece, 2019

- Chatzimichalis, Kostis. “Debt crisis and land grabbing”. Athens: KPSM, 2014

Footnotes

- Rolnik, 2013; 2019[↩]

- As a means of trading products, calculating value and accumulating wealth.[↩]

- Capital refers to assets as a productive factor, but equally to financial assets (shares, bonds) that aim to increase the initial working capital, e.g. when a company issues shares and sells them on the stock exchange, it increases its capital, but not necessarily its cash reserves, but rather an obligation to repay the capital borrowed today with an interest calculated as a future return.[↩]

- Aalbers, 2016; Beswick et al., 2016; Fields, 2017; Belotti & Arbachi 2019[↩]

- Kemeny, 2006[↩]

- Christophers, 2017; Coq Huelva, 2013[↩]

- Forrest and Hirayama, 2015[↩]

- Adkins et al., 2020[↩]

- Lapavitsas, 2013; Chatzimichalis, 2014[↩]

- Gotham, 2009[↩]

- Gotham, 2009[↩]

- Harvey, 2018[↩]

- Alexandri and Janoschka, 2018[↩]

- Aalbers, 2019[↩]

- Lamarca and Kaika, 2016[↩]

- Haila 2016[↩]

- Janoschka et al., 2020[↩]

- Smith, 1996[↩]

- Gotham, 2016[↩]

- Haila, 2016[↩]

- Leontidou, 1989; Mantouvalou and Mavridou, 1993[↩]

- Emmanouel, 2014[↩]

- Polyzos, 1985[↩]

- The Workers’ Housing Organisation (OEK) was abolished in 2012 as part of the 2nd Memorandum’s prerequisite, even though it was one of the healthiest state institutions, with substantial reserves.[↩]

- Dagkouli-Kyriakoglou, 2018[↩]

- Emmanouel, 2014[↩]

- Alexandri, 2022[↩]

- Siatitsa, 2019[↩]

- Alexandri and Janoschka, 2018[↩]

- Alexandri, 2022[↩]

- Bank of Greece, 2019[↩]

- Alexandri, 2022[↩]

- Alexandri, 2022[↩]

- ibid[↩]

- ibid[↩]

- ibid[↩]

- Alexandri, 2022[↩]

- ibid[↩]

- At the time, most foreclosure auctions were fruitless, due to low demand. According to the Law, the property has to be auctioned until a buyer is found. The third time an auction is organised for the same property, the starting price can be up to 65% lower than its initial value (Articles 927- 2021 of the Penal Code).[↩]

- Alexandri, 2022[↩]

- ibid[↩]

- The European Union, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund.[↩]

- ibid[↩]

- ibid[↩]

- After all, our governments have been watching closely the political developments in Spain after the rise in power of Podemos, a political party that was defending the right to housing of 500.000 households that lost their houses to funds through securitisation processes.[↩]

- Alexandri, 2022[↩]

- ibid[↩]

- Alexandri, 2022[↩]

- Balabanidis and Papatzani, 2022; Lialios, 2021; Pettas et al., 2021[↩]

- Pettas et al., 2021[↩]

- Alexandri, 2022[↩]

- ibid[↩]

- Balabanidis et al., 2021; Gourzis et al., 2021; Pettas et al., 2021[↩]

- Alexandri, 2022[↩]

- ibid[↩]

- Alexandri, 2022[↩]

- Alexandri, 2022[↩]

- Alexandri, 2022[↩]

- Alexandri, 2022[↩]

- ibid[↩]

- ibid[↩]