Murray Cox: the activist who dissects Airbnb

Murray Cox is one of the founders of inside airbnb, a free access platform with aggregated data on Airbnb in specific locations worldwide

In the summer of 2014, Murray Cox found himself addressing a young audience in Brooklyn. Using maps and statistical methods, he attempted to describe to children aged six to thirteen a condition that the local community had already begun to notice: the housing crisis, gentrification, rising rents and rising homelessness.

Around the same time, journalists in the US had started writing about Airbnb, without presenting graphs, maps or primary data, though. Most of the articles were about San Francisco and New York, when a trend that has now become dominant began to emerge: most hosts were not just renting out a few rooms to guests and visitors, but entire houses.

For Murray, the issue was obvious. The lack of available data masked the magnitude of the problem in the large urban neighbourhoods. Then it occurred to him that he could do the job himself.

His technical skills proved to be extremely useful. As a programmer, Murray began collecting data regarding his own neighbourhood, Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn, New York. He plugged the data into an Excel spreadsheet and realised that in a neighbourhood of 100,000 residents, there were 1,000 Airbnb listings. What he noticed relatively quickly was that the pattern he had detected in other neighbourhoods applied in his as well: namely, that people who owned more than one property were making them available on the platform for short-term rentals.

The next question that naturally arose for Murray was what to do with this data. He thought it would be useful to create a platform where people could download the data, and incorporate interactive graphs that would give a clearer picture of the issue. By February 2015, Murray had published data for the entire city of New York.

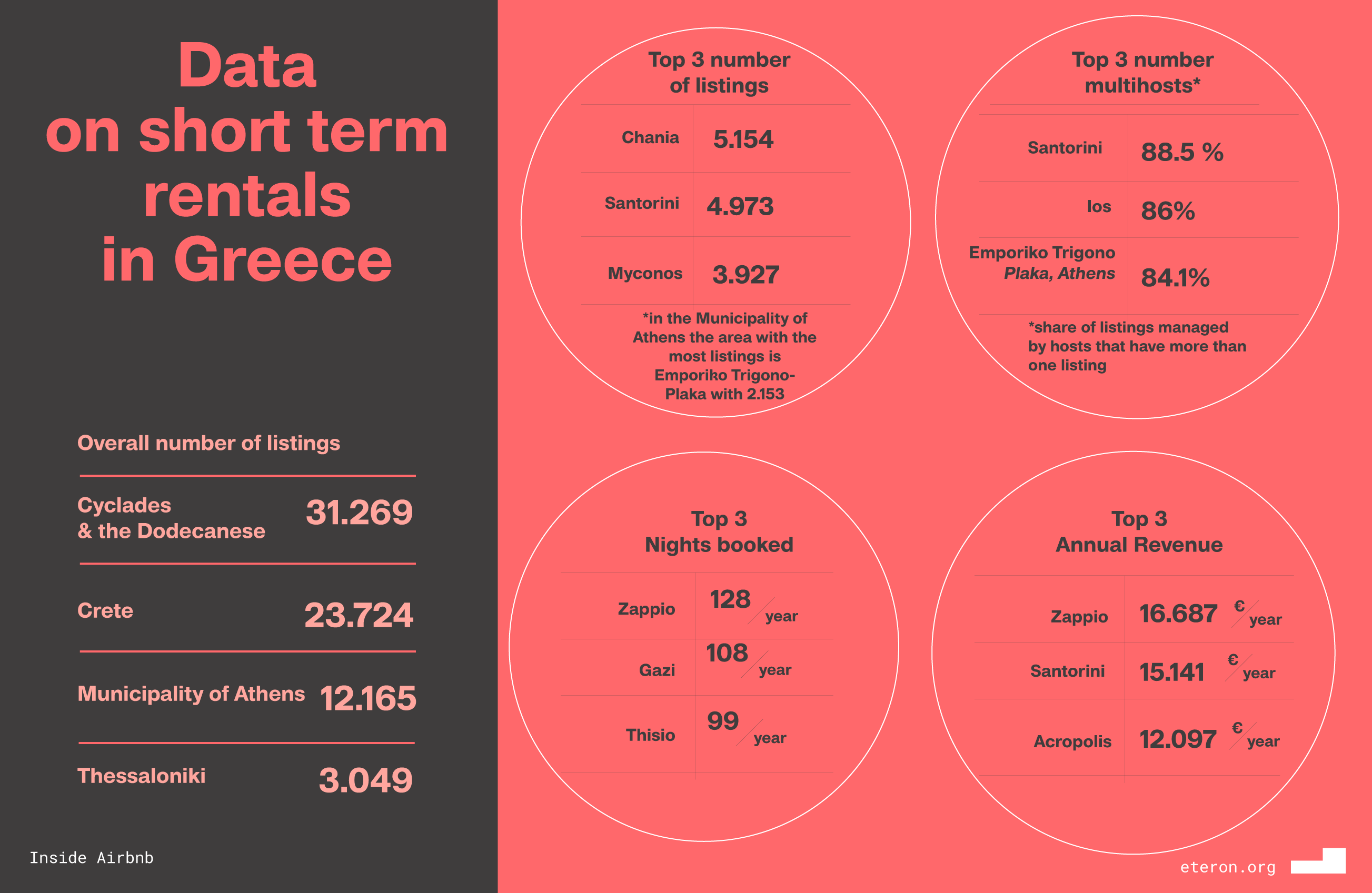

After the launch of this platform, journalists, activists and residents requested data on their own neighbourhoods, cities and countries. Today, Inside Airbnb hosts data for more than 100 cities. Greece is among the countries included in this extensive database, as it contains data regarding Athens, Crete, the South Aegean and Thessaloniki.

Especially for the Municipality of Athens, the figures are overwhelming. Murray cites more than 12,000 Airbnb listings, with 90% of them being entire houses or flats rather than rooms. At the same time, 60% of the listings are by owners who have more than one property for short-term rental. These are often referred to as multi hosts.

When Murray visited Greece in the autumn of 2022 for an event organised by the Hellenic Chamber of Hotels, he saw it as an opportunity to talk to local platform hosts and activists, but also to wander around the city in order to better understand the story behind the data he has been collecting for some time. As part of the Eteron’s “Sky-high Rents” project that we have been running for over a year now, we conducted an interview with Murray, through which we hope to gain an even better understanding of the scale of the problem and the components of its solution.

The image he got for the centre of Athens and especially for the area around the Acropolis was that these were neighbourhoods just heavily geared around tourism. In addition to the high concentration of tourist accommodation, Murray noticed that most streets in the centre of Athens are filled with restaurants and eateries.

As he ventured further away from downtown Athens, the scene was different. There, the neighbourhoods were more vibrant, reflecting a better balance between visitors and locals.

From his experience of researching and analysing the housing issue, Murray believes that the main impact of short-term rentals is a shrinking of the housing stock, i.e. the properties available for long-term rentals. In other words, the houses people live in. This condition affects not just tenants but also potential buyers looking for a property to house themselves and/or their families.

Murray also spoke of speculative practices, with investors from all over the world buying hundreds of properties in their own country or even in other countries, driving up housing costs and reducing the housing stock, as many of these properties end up in the short-term rental market.

Another issue that arises is the disruption to the quality of living for residents who happen to live in apartment buildings and streets with high concentrations of Airbnb listings.

“Tourists arrive every day or every week, disturbing the inhabitants’ peace. There are residential areas, such as neighbourhoods in suburbs, where the quality of life of those living next to Airbnbs can be negatively affected, as some flats turn into party houses”, Murray said.

Globally, the spread of Airbnb started in 2015. From that point on, according to Murray Cox, there were cities that saw a 50% to 100% increase annually in the number of listings.

This phenomenon was even more prominent in global metropolises such as New York, Paris and London. New York, for example, the first city that Murray started tracking and mapping, had 20,000 listings in 2015. By 2019, that number had gone up to 50,000.

2019 was also the year that completely changed the short-term rental scene: privately funded companies and venture capital firms emerged as managers of dozens of Airbnb properties.

This reality inevitably began to cast a shadow on the narrative that views Airbnb as a valuable tool in the hands of the economically poorer classes.

“The basic argument is that short-term rentals are an economic tool for poorer neighbourhoods because people can earn extra money by renting out their home. The question here is who can rent their home short-term?” Murray wonders.

Furthermore, adds Murray, we need to raise the question of how short-term rentals affect access to housing. Does this practice deprive local communities of available homes? At what point do we define the existing situation as over-tourism? Do we want to create Disneyland-type zones where there will be no locals and those who work there will have to commute from further and further away in order to get to work every day?

At the same time, the platform’s founder addresses the counterargument that exists worldwide. It is argued that the shift towards a short-term rental model democratises tourism by providing an alternative to large hotels and distributing the profits to residents in a more horizontal way. So in Italy, for example, some argue that Airbnb is boosting sustainable tourism by bringing the Italian countryside back to life. This is a very important discussion, especially for countries that are heavily dependent on tourism, such as Greece.

In reality, however, the explosive spread of Airbnb across the world caught most countries institutionally unprepared. In some cases, the existing legal framework made the platform’s operation, if not illegal, at least controversial.

One of the first cities to design a regulatory framework for short-term rentals was San Francisco. The measure stipulated that hosts could not rent their properties for more than 90 days per year. Prior to the implementation of this measure, San Francisco had about 8,000 listings. After its implementation, listings dropped to less than half that number.

Similar attempts to regulate the phenomenon of excessive short-term rentals are being made in Berlin, Barcelona, Amsterdam and elsewhere. In some cases, where the authorities are more reluctant to impose restrictions, registers have been set up so that there is at least some official record of short-term rentals in certain areas.

“It’s interesting to see how the market responds to regulatory measures. I’m thinking of an Airbnb host who has moved to a longer-term rental model and so, for example, instead of renting out his property for two or three nights, he’s now renting it out for 30 consecutive days. So the market is basically reinventing the way it operates under the new regulations” Murray comments.

Murray reckons that in cases such as Greece’s, where housing policy is very much dependent on national legislation, things are somewhat more complicated.

In contrast, in countries where housing is regulated locally, activists are better placed to put pressure on local authorities to make changes. So we see, for example, the housing movement in Barcelona pushing the regional government in Catalonia to implement regulations, while in France, Paris had to join forces with Lyon and Bordeaux to get interventions at a national level.

“This situation just makes it more difficult because most movements don’t have the necessary connections that would allow them to influence some MPs and change the law. So they end up relying on other groups, such as the hotel sector, an industry that is usually not friendly to movements fighting for their right to the city.”

“Generally speaking”, Murray concludes, “I think that it’s necessary to form more alliances between movements, not just within cities, but also between different cities and regions. This way our voice will be heard when discussions about regulatory measures are being held, especially at a national level. I have seen it happen and have myself participated in such struggles.”