6 key points that were absent from the government’s housing plan

Since the beginning of 2022, Eteron’s project “Sky-high Rents” has tried to highlight the significance and scale of the rental housing issue, as well as its various aspects. Moreover, in June, we published the “Policy Paper: For the right to affordable rental housing”, which included specific policy proposals and requests in order to effectively address said issue.

On 10th September 2022, the Prime Minister finally announced the government’s policy plan regarding housing, and on 15th September the measures were presented in more detail by government ministers at a press conference.

Of course, the recognition of the problem and the formulation of specific proposals to address it is in itself a positive development. However, we need to carefully evaluate the proposed measures to see whether they will bring about meaningful improvements for tenants, thus reducing the housing insecurity in which they live and the increased risk of impoverishment to which they are exposed.

In fact, it is difficult to evaluate the measures suggested by the government, as their efficiency will depend on the conditions of their implementation. However, the shortcomings that do exist are indicative and show that unless there is political will to address them in an appropriate manner, it is very much likely that resources will be wasted without achieving the expected social impact.

In the following paper we shall identify and analyse 6 important gaps and shortcomings that we believe should be taken into account in the public debate.

1.Rental housing market regulation

Α. Rent Control

The fact that rent control as a measure wasn’t even mentioned in the government’s suggested interventions to tackle the housing crisis, was a serious omission. Given the exceptional circumstances of high inflation, the energy crisis and the extremely overburdening of the majority of Greek households, the current conjuncture calls for emergency solutions. One of the measures suggested by the research working group in Eteron’s “Policy Paper: For the right to affordable rental housing”, was rent control.

More specifically, the authors note that “rent control refers to a number of interventions in the private rental housing market, aiming mainly to mitigate the overwhelming increase in rents. The three main intervention methods are: a) imposing a rent cap in all new leases, b) controlling rent increases for lease renewals and c) control yearly appreciation rates for active leases. In Greece such measures have been implemented on different occasions, when said measures were deemed necessary due to “emergency situations”. The most recent example was during the pandemic health crisis, when the State decided to intervene in the private rental housing sector. This proves the argument that [implementing such measures] is in fact a matter of political will, funds’ allocation and additional support through other relevant policies.

What can be done?

According to Eteron’s research working group, the following measures could be implemented:

- The present situation of runaway inflation and the cost of living is an emergency situation that adds excessively on households’ living costs. Under these circumstances, a rent appreciation ban and the imposition of caps on new leases based on benchmark prices (e.g. based on a study of average prices from the e-leasing platform of the Independent Authority for Public Revenue – IAPR) could be immediate but temporary interventions to contain prices, with continuous monitoring to avoid creating two-speed markets.

- At the same time, the methodology and indicators required for the establishment of a list of reasonable rental prices per region according to dwelling characteristics need to be defined.

- In any case, it is necessary and also crucial to differentiate the approach towards landlords based on a number of criteria: type (natural person or legal entity, small landlords or large investor/ companies), income (different terms for small landlords with financial difficulties and others for high-income owners), the scale of the rental housing stock they manage and the type of activity/use (primary residence, short-term rentals, serviced tourist rentals/luxury homes, etc.).

- In the long term, the aim is to establish a stable framework for monitoring and controlling the rental housing market (also see key point 6).

Β. Social and affordable housing in the existing stock

Given the large existing housing and building stock in Greek cities, it is crucial to develop tools that would facilitate the conversion of houses and/or whole buildings, regardless of whether they belong to the State or to private individuals/ companies or whether they are currently inhabited by tenants or are vacant, in order to increase the supply of affordable rental housing. To this end, the government announced its intention to renovate 14,000 vacant houses in order for them to be used as long-term rental properties. However, if we compare this number with the total number of vacant houses in Greece (770,000 according to the government and 900,000, according to the Hellenic Statistical Authority’s 2011 census), we understand that the potential for intervention is significantly greater. At the same time, many additional measures could be taken for the reintegration to the long-term rental market of properties beyond those that are currently vacant.

What can be done?

As elaborated in Eteron’s Policy Paper, it is necessary:

- To implement incentives for the landlords/ property owners, in order to entice them to participate in the aforementioned model that includes rents that are below market averages. Also, an effort should be made to secure programme partnerships with large landlords such as the public sector, banks, foundations, the Church etc. Incentives may vary depending on the legal status and income of the landlord and don’t need to be restricted in funding for refurbishment or energy upgrade of their property. For example, they could include guarantees on behalf of the State that the rent will be paid and that the properties will remain in good condition. Other incentives could be one-off subsidies to reactivate vacant properties, offering home insurance as well as tax incentives (e.g. reduction of Uniform Real Estate Property Tax – ENFIA, exemption or reduction of rental income tax, etc.).

- To ensure administrative infrastructure, institutional tools and adequate scientific staffing of the bodies that would acquire and (be able to) make good use of the properties that would participate in the scheme.

- To secure different sources of funding, that would ensure the intervention’s viability, such as making use of subsidies granted for property upgrades and refurbishments (e.g. funds available via the Energy Saving at Home programme and the Recovery Fund for renovations), and also creating a link between this policy and rent subsidies (to support households with limited economic capacity or to boost the income of households who on occasion are experiencing financial difficulties and find it difficult to cover their housing costs).

- To develop a range of services in order to ensure the most efficient mediation between landlords and tenants, such as legal counselling and aid, in case of legal disputes, technical support, conflict resolution, interpreting, personalised support services for vulnerable groups, etc.

C. Tenants’ protection and empowerment

Respectively, there should be a protection and empowerment framework in order to support tenants. Given the fact that in Greece, tenants have very little/weak representation while at the same time there is a lack of tools and mechanisms for monitoring, documentation and intervention in the rental housing sector, there is a need for:

- Better rental sector monitoring by setting up a Housing Observatory and establishing fair rent indicators.

- Tenant support services and more specifically: i)To raise awareness and provide information on the rights and obligations of tenants and landlords, ii) Establish minimum suitability standards for rental housing as well as control and assessment bodies/ mechanisms, iii) Establish an institution that would act as the “Tenants’ Ombudsman”, iv) Establish a framework that would provide for tenants’ and landlords’ consultation and participation in the assessment and development of the institutional framework and policy tools and v) Set up a household support programme, run by the local authorities, to provide emergency and temporary financial and counselling support to households in financial distress due to difficult circumstances (e.g. unemployment, health problems, etc.) and to help them recover.

2.Short-term leasing/ Airbnb regulation

The fact that there aren’t any government intervention proposals regarding the regulation of short-term leasing through platforms, is in itself a very significant omission. This creates insurmountable problems when it comes to tackling housing insecurity, since malfunctions that have emerged over the past few years in the rental housing sector point to the lack of short-term leases’ regulation as being a deciding factor.

The way that the expansion of the short-term leasing phenomenon affects the rental housing market is simple. Since said activity is more lucrative, more and more property owners choose to withdraw their houses from the long-term rentals’ market and only make them available through short-term leasing platforms. Therefore, supply decreases while demand levels remain the same – or even increase – and as a result, the rental property prices increase.

This phenomenon has specific geographical characteristics as already analysed in a paper written by D. Balampanidis and E. Papatzani in February 2022 for Eteron, since cities and areas of tourist interest present a strong concentration of properties only available for short term lease (Athens, Thessaloniki, Crete, islands). Besides, recent cases that have been brought to the spotlight regarding the difficulties faced by teachers, doctors and students who are struggling to find accommodation in said areas are directly linked to this trend. In the same paper, the authors also highlight another important characteristic of short-term rentals: the tendency for flats to be concentrated in the hands of property management companies, thus giving them considerable bargaining power in setting prices, while at the same time raising questions about the distribution of the surplus value generated by short-term rentals. As stated by D. Balampanidis and E. Papatzani, “the number of hosts who list more than two different properties on the platform is increasing constantly (reaching over 62.5% at this time), while at the same time, more and more property management companies enter the Airbnb market, some managing tens of properties (some have a portfolio of over 160 properties)’’.1

According to certain articles in the press, the government chose not to delve on the issue of short-term leasing because of the lack of stability that exists in this particular market. But on the one hand, the very lack of stability is mainly due to the pandemic that has affected the entire tourism industry, while on the other hand, the absence of regulation is a crucial factor that puts further upward pressure on rents.

What can be done?

In the “Policy Paper: For the Right to Affordable Rental Housing” published by the Eteron research group in June 2022, a set of actions on this issue is outlined. Suggested actions include:

- Issuing the Joint Ministerial Decision (JMD) provided for by Law 4472/2017, according to which for reasons related to the protection of the right to housing, it is possible to define certain geographical areas in which stricter (and differentiated) restrictions on the availability of properties available for short term leasing shall apply. Namely: a) only allow for 2 properties per TIN to be made available for short-term leasing b) each property can be leased for a maximum of 90 days per calendar year or, in the case of islands with less than 10,000 inhabitants, 60 days per calendar year (Law 4472/2017, article 84, paragraph 8) and c) the distinction between companies and small landlords. This Joint Ministerial Decision needs to be amended not only in the light of the new data available on the increased involvement of management companies in short-term leases, but also on the basis of the effectiveness of the provisions it includes. For example, the 90-day limit needs to be revisited, as the practice of long-term leasing for only a few months each year, which has been observed in some of Greece’s most touristic areas, is already creating problems for long-term tenants (there are cases of evictions during the summer, when the owner wishes to rent out the property on a short-term lease). Below we list some alternative suggestions:

- Adopt stricter, geographically defined measures in areas with high tourist activity and limited housing stock available for long-term rentals. These areas can either be entire small towns and islands or, in the case of large urban centres, specific neighbourhoods where the problem of inaccessibility to rental housing has become particularly acute. In areas that have a larger available housing stock and less tourist activity, the levels of short-term rentals can be maintained or even vary on a case-by-case basis, always within a comprehensive plan for tourism.

- Adopt a differentiated approach to the short-term leasing activity depending on whether there are companies or individuals that are involved, and implement different measures on a case-by-case basis.

- Adopt measures to help regulate the coexistence between permanent residents and the tourists who use the apartments, in buildings where there is short term rental activity, focusing on building safety and security, the use of the infrastructure and with respect for the needs of the permanent residents.

- Continuous monitoring of short-term leases and control of property uses in different regions of the country so that the above regulations and restrictions can be adjusted geographically when necessary.

- The above regulations should be integrated into a more comprehensive strategic plan not only for affordable housing but also for sustainable tourism, in order to avoid the phenomenon of “overtourism” that is already affecting parts of the country.

Use of Recovery Fund (RRF) resources

One of the major difficulties in implementing a coherent national housing policy is that it requires substantial financial resources and large public expenditure. The investments required for the construction or renovation of buildings, the combination of tax incentives, guarantees in the banking system, etc., raise the financial bar considerably, especially in countries such as Greece, where fiscal constraints make this problem more acute.

The implementation of the Recovery and Resilience Fund, amounting to approximately €800 billion, as a response to the recession caused by the pandemic at a European Union level has been an impressive injection of resources to Member States and a great opportunity to redefine national priorities and address structural issues.

The Greek plan involves a total of €30.5 billion (€17.8 billion in grants and €12.7 billion in loans).

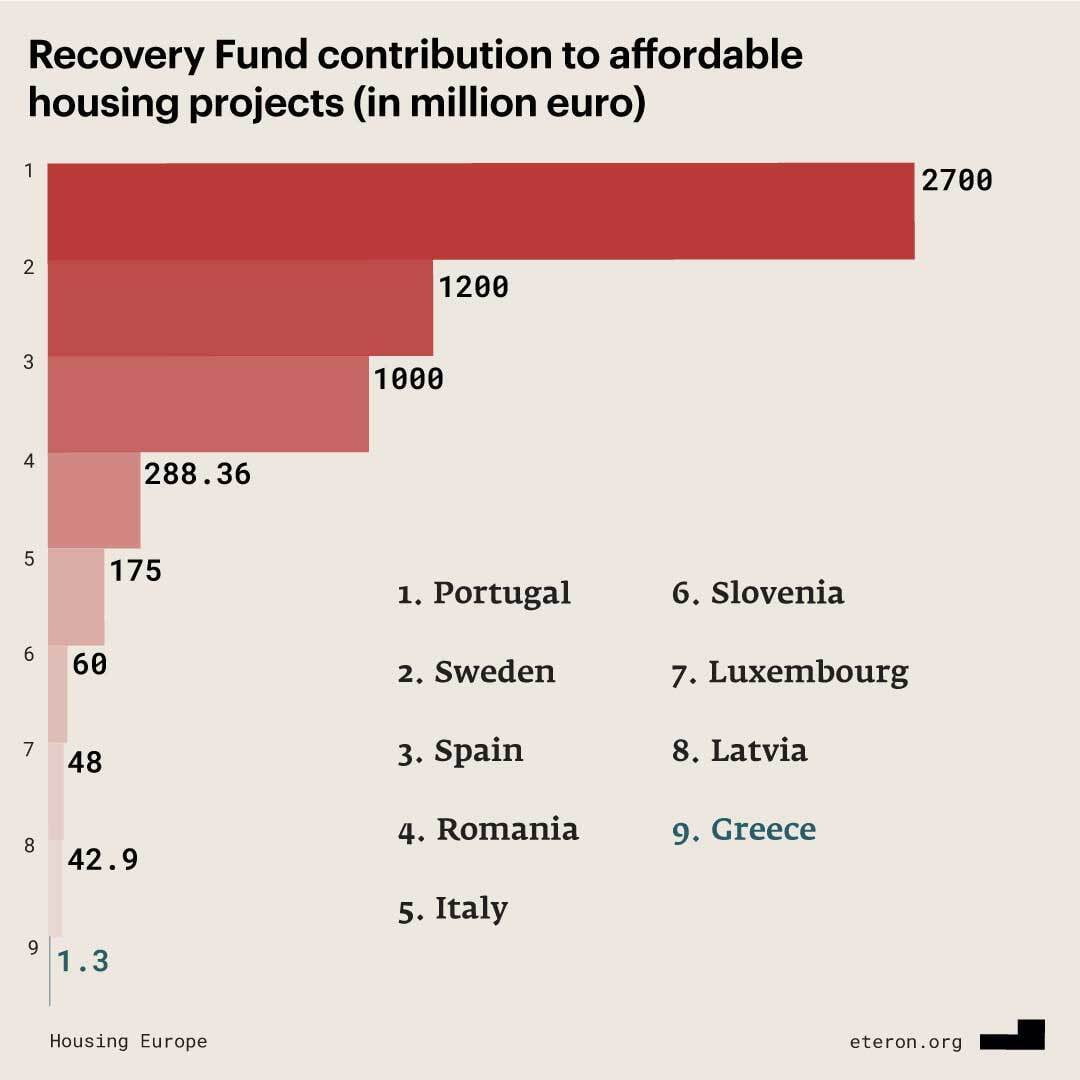

Of these, only €1.3 million is allocated to measures relevant to affordable housing, an impressively small percentage of the total package, indicating that either until the summer of 2021, when the Greek plan was approved, the housing issue was not on the government’s priority agenda, or that for some reason the Recovery Fund was not considered a strategic opportunity to address the housing issue.

The Greek plan provides that said €1.3 million will finance the renovation of 100 flats (70 in Athens and 30 in Thessaloniki), which the landlords will then opt to rent out to vulnerable households at a low cost, in cooperation with local authorities.

In order to be able to compare similar programmes in other European countries, we present below the way that eight other European countries have chosen to use the funds from the RFF in order to boost affordable housing:

- Portugal has designed the housing programme with the highest budget using the €2.3 billion it received through the Recovery Fund. Its programme is divided into six actions of different types and targeting. Among the programme’s objectives is the construction of 12,000 apartments that will be rented at low rent, thus increasing the housing stock.

- Spain is financing a €1 billion affordable housing construction programme, aiming to build and deliver at least 20,000 flats in areas with the most severe housing and rental problems.

- Italy has designed a €175 million programme using resources from the Recovery Fund that will be supplemented with national resources and other funding schemes, which will be used to build affordable housing and provide services to people facing housing problems. The social groups that will mainly benefit from said programme are young people, people with disabilities and elderly people in difficulty.

- Sweden will use €1.2 billion from the Recovery Fund to finance existing social housing schemes and renovate the existing rent-controlled housing stock in order to make it socially and financially affordable.

- Romania will allocate €288 million from the RRF to finance the National Spatial Development Plan for the reduction of spatial and regional disparities. This money will be used to build new social housing, student residence halls and apartments for doctors and teachers in remote areas.

- Latvia will finance a €42.9 million social housing construction and renovation project (700 apartments) as well as targeted actions to assist the elderly.

- Luxembourg will invest €48 million from the Recovery Fund in a €51 million national programme for the construction of affordable rental housing, aiming to build 2,200 flats by 2025, of which 1,700 will be rent-controlled, affordable apartments.

- Slovenia will commit €60 million from the RRF to its national rental housing programme (that has a total budget of €400 million) to construct low-rent flats for young people, vulnerable groups (e.g. Rom), domestic violence survivors. The aim is to build 5,000 such apartments by 2026.

From the above, the conclusion we draw is that countries facing serious housing issues choose to use the Recovery Fund as a strategic tool for financing their national housing programmes, which is not the case in Greece. The comparison of the Recovery Fund resources allocated to affordable housing schemes becomes even more unfavourable for our country, when compared to others with a similar population in terms of numbers.

4.Additional regulations regarding Golden Visas

One of the measures announced by the government in order to address housing-related issues, was the increase of the investment threshold for granting residence permits to third country citizens from €250,000 to €500,000.

This investment program, apart from the moral criticism that it has justifiably received, since it enables the sale of residence permits to wealthy residents of third countries while a tough – and in many cases illegal – immigration policy is being enforced, also runs the risk of being a huge window of opportunity for the legalisation of illegal revenues.

At the same time, the Golden Visa program has an adverse effect on the housing market since property acquisitions in Greece through this scheme increase property prices, while, in most cases, said properties don’t enter in the rental housing market. They therefore reduce the supply of properties that are available for rent, thus increasing rental costs.

It is worth noting that, according to a published study, while in most European countries where the Golden Visa investment scheme is applied, the impact on the real estate market is insignificant, Greece is an extreme exception, since the real estate market in our country, according to the data, is significantly influenced by investments related to the granting of those “golden” residence permits. According to this study, in 2018, golden visa transactions in Greece accounted for 35.9% of total transactions that took place in the Greek real estate market, with all that this implies in terms of pressures on the latter. In the same year, transactions for golden visas in Portugal constituted only 2.9% of the transactions in the country’s real estate market.

At first glance, the measure to increase the investment threshold for obtaining a Golden Visa, shows that there is an acknowledgement of the adverse impact of these investment schemes on the housing market.

However, increasing the threshold without applying any other criteria may prove to be insufficient. The reason is that given the considerable cash flow of third country citizens and the constant need to legalise income, raising the threshold may simply increase real estate purchases in our country, since the threshold functions cumulatively for such investments. This way, instead of buying one property worth 250,000 euros, one can buy two properties worth 250,000 euros each, thus aggravating the existing dysfunction of the real estate. In other words, if the demand for property purchases that can grant third-country nationals a golden visa turns out to be inflexible (there are good reasons to believe that this is a possibility), the measure might cause results that will be the exact opposite of the desired one.

What can be done?

In any case, the measure to increase the golden visa threshold should be accompanied by additional regulations that would ensure that it stops reinforcing the upward trends in the housing market.

Some of the possible ways for the above to be achieved are:

- The complete abolition of Golden Visas for investments in residential real estate.

- The geographical specification of restrictions in order to protect areas that are already under significant pressure, the way that Portugal has done, for example, by banning such practices in major urban centres (Lisbon and Porto) as well as in certain touristic areas of the country. On 15/09/22, the Minister of State, Akis Skertsos, mentioned Portugal as an example of good practice in regulating this particular investment opportunity, advocating for the specification of housing-related measures, without, however, mentioning the additional restrictions imposed by the country on the Golden Visa regulation.

- Tools to strengthen the transparency of such investments, in order to ensure that these investments can be identified, thus allowing the state to intervene in a concrete and effective way.

- Definition of permitted uses (e.g. only owner occupation and not use of residential properties as tourist accommodation).

5.Social Economy

A major structural deficiency in the government’s housing policy proposals that could effectively reduce rents and create a new paradigm, is the complete absence of social economy, the so-called “third sector”, according to European standards.

Let’s take for example the government’s announcement of the so-called “social antiparochi” 2) (i.e. land for flats). This will involve the granting of state-owned properties to private developers who will construct, at their own expense, modern residential buildings, of which they will be obliged to lease 50% at a low cost to new beneficiaries and can then commercially exploit the rest.

The effectiveness of this particular measure -besides any other criticism one could make- is questionable, since the final determination of the so-called “low” rental cost rent that would apply to 50% of the apartments, will be the product of negotiations between construction and real estate companies and the state institutions. Entrusting the construction and management of these dwellings to the for-profit sector reduces the social effectiveness of this measure. At the same time, the exploitation of the remaining 50% of the new apartments based on commercial, for-profit criteria acts as an incentive for the construction companies to make up for any lost profit from the “low” rent, on the remaining 50%, thereby reducing the overall impact of the measure.

What can be done?

In this case, the existence of an institutionalised limited or even non-profit housing sector, which would be integrated into the existing institutional Social Solidarity Economy framework, would provide the necessary guarantees that all the new apartments could be made available at a really low rent, reflecting the real costs of construction, maintenance and management of the new apartments. Moreover, at the core of such an option would be that access to decent housing is a social good and a human right, rather than an investment product and a vehicle for speculation and enrichment.

Such an approach would benefit the rental housing market in many ways, as it could put downward pressure on rents in certain areas and operate “competitively” towards those who gain significant surpluses from high rents to the expense of tenants. This would be a breakthrough in the rental housing market that would encourage a new housing policy paradigm.

There are two main advantages that render this proposal entirely realistic.

First of all, the limited or even non-profit housing sector is a reality in many European countries and operate in a way that ensures socially affordable housing and a more equitable income distribution. Austria’s case is perhaps the most striking in this particular field, with very significant positive effects for society and the economy. The Austrian Institute for Economic Research’s survey on this topic in March 2021 is highly illustrative.

Secondly, the development of the Social and Solidarity Economy in our country in recent years is becoming a reality. More and more social enterprises and cooperatives are becoming active in various sectors, they network, find funding tools and develop within the context of what’s called social entrepreneurship. Given the existing legal framework and the experience gained, supporting this sector in the field of affordable housing could create multiplier benefits in Greece. If this support were linked to the Recovery Fund and other financial instruments with the assistance of the relevant authorities, we could have a paradigm shift in housing policy in Greece.

6.Institutional support/ coordination

A significant concern regarding the housing policy measures announced by the government is the absence of well-organised institutions that will coordinate the relevant actions and programs, collect data, produce analyses and forecasts that will help to evaluate the policies followed and redirect actions in line with social reality, when needed.

Today, this role is to be filled by the Public Employment Service (DYPA), which falls under the Ministry of Labour. Historically in Greece, this particular Ministry has had in its mandate issues related to social protection and social policies. However, there is cause for reasonable doubt as to whether a public organisation such as DYPA can, along with its other responsibilities, play a key role in the design, implementation and evaluation of housing policy.

The impression that the government announcements are made without first being based on studies that take into account price developments in the housing market for each region, trends regarding rents in different areas of the country, the impact of recent changes in the housing market due to short term rentals or golden visas, the impact of spatial changes on city plans, the economic and social parameters that determine the household disposable income, raise doubts about the effectiveness of the announced housing policy.

What can be done?

It is necessary to establish a competent body (in the form of a research organisation) that would collect and analyse data and evaluate housing policies, in cooperation with higher education institutions and local governments.

It is also important to have a single institutional centre that is responsible for housing policy, not as a mere side-task, but as a central focus for the development of a national housing policy that is specific to each geographical area and each social category, while at the same time it will be able to gather resources from different funding schemes that are currently scattered. The establishment of a Ministry responsible for housing policy that the Prime Minister announced a few months ago would be an important step in such a direction, but such a step was absent from the recent measures package that was finally announced.

Epilogue

It should be common ground by now that the housing issue in Greece, especially in what concerns the rental sector, requires policies that will set rules and requirements in a long-standing unregulated market, will give the state and society tools that will enable a more rounded monitoring of relevant developments, will act as a protection for the ever-expanding array of vulnerable social groups and will create a framework that will allow social economy actors to be active in the construction and management of housing properties. Unfortunately, however, the government’s measures are more likely to take the very same path that has led society into conditions of severe housing insecurity. The market remains largely unregulated, while the proposed measures once more focus on owner-occupation, construction activity and mortgages. At the same time, the public sector remains essentially uninvolved, as the government seems to be conspicuously ignoring the role that public bodies could and should play in the implementation and management of its proposals. In this context, and given the complete absence of any reference to the role of the social economy, it is impossible to believe that these measures will change everything that is wrong with housing in Greece.

By Alkis Kafetzis, project coordinator “Sky-high Rents | Housing insecurity today”

Footnotes

- The top-5 property owners in the Greek short-term rental market, own 564 properties (September 2022, source Airdna). [↩]

- Antiparochi is a uniquely Greek arrangement, whereby the owner of a building plot was compensated with apartments in lieu of payment for the land that he relinquished to the contractor who built an apartment block on it[↩]