The changing housing landscape in Greece and “Generation Rent”

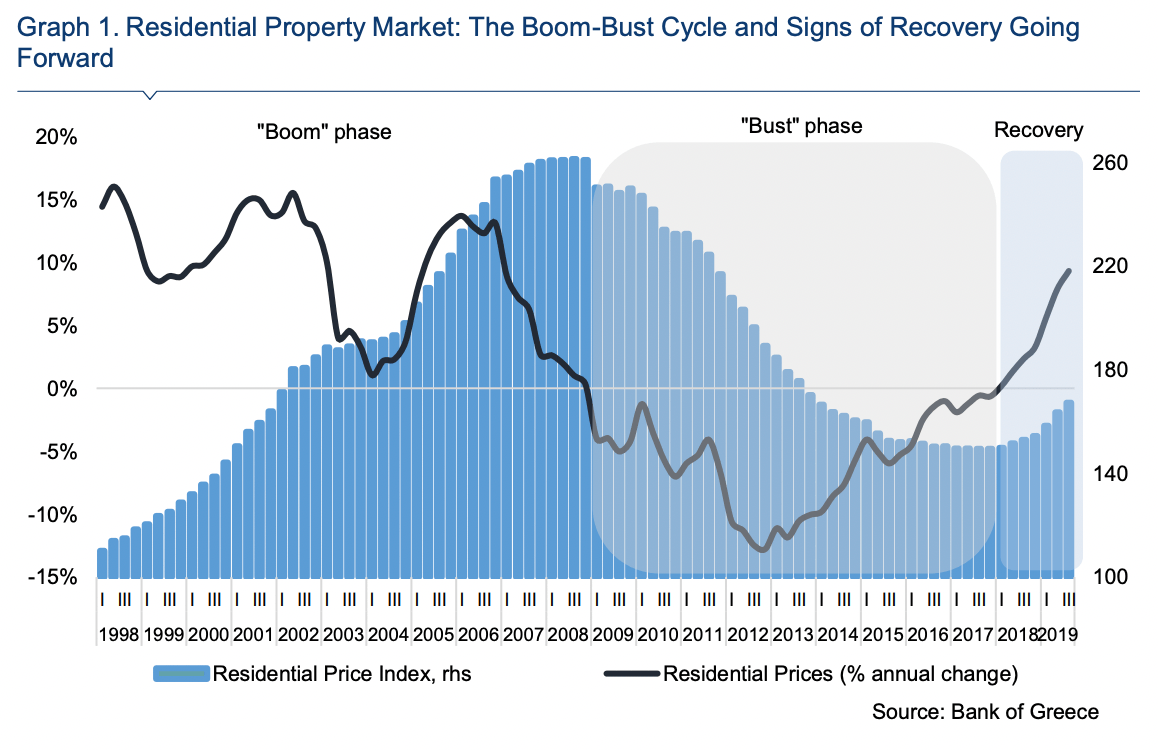

In January 2020, Alpha Bank published an economic report regarding the real estate market in Greece. Its statistical graphs clearly depict the transformations that have been taking place in the housing sector for the past 15 years, raising questions about whether or not the predominant housing access model since the Interwar years, is still able to fulfill the needs of Greek society, and if so, to what extent. The cracks on the surface run increasingly deeper, thus affecting many of us.

Graph 1. Residential property buying in Greece in the last decades (1998-2019): Boom, recession, recovery period 1

Rent at several areas of Athens has increased by more than 50% compared to 2017, and a significant raise (30-40%) has been observed in other Greek cities, such as Thessaloniki, Patras and Volos 2. Of the 26,5% 3 of Greece’s population who live in rented houses (though the percentage is significantly higher in bigger cities and touristic destinations, reaching 40% in Athens’ city centre and in islands such as Mykonos) 4, 83,2% stated back in 2019 that they spend over 40% of their income to cover their housing costs 5. If we add to the above, the rent increases in 2020-2021, the revaluation in energy rates and the general costs’ increase due to inflation, it’s safe to conclude that it’s increasingly hard for households to maintain affordable housing.

Some of the predominant housing system’s basic traits are high percentage of owner-occupied dwellings and a prominent role of the family and family-owned property as means of covering the population’s housing needs 6. With that in mind, how significant is the rent cost increase problem for Greek society? Who does it really concern? Will the distinct traits of the Greek housing system prevent a full-blown housing crisis, like the ones in other cities, mainly in Western Europe?

Let’s have a closer look at certain data that will allow us to deepen our understanding of the issue at hand, keeping in mind that each of the topics we’ll raise, could very well be the subject of more elaborate analysis:

Renting is widely considered to be a transitional stage in a person’s typical housing pathway, that is usually between living at one’s parents’ house and buying one’s own home. This perception still exists nowadays, with homeownership being a desired, if not an expected outcome at some point after the age of 30. According to a study by Dewilde 7, that age has moved after 34 across Europe, as opposed to what the case was prior to the economic recession (as per data between 2005-2018).

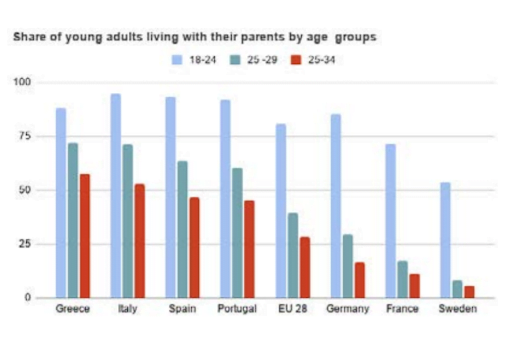

Adding to the delay described above, there are two more findings that show that the typical housing pathway we’ve mentioned earlier, has been changed on a European scale in the past 15 years, and even more so in Greece. Due to the economic recession, many young people adapted to the new circumstances by returning to their parents’ houses. According to the Hellenic Statistical Authority, Greece holds one of the highest percentages of young people aged 18-34 who live with their parents 8. The percentage remains high even in the age bracket of 25-34, when in Europe there’s a significant decrease in that group, something that shows the young Greek people’s substantial delay in catching up with the typical housing pathway. This delay has become even more significant from 2014 onwards, with percentages reaching 66,7% for the ages of 18-34 in 2017 and 69,4% in 2019, when in 2008 it used to be 58,4% 9.

Graph 2. Share of young adults living with their parents by age groups 10.

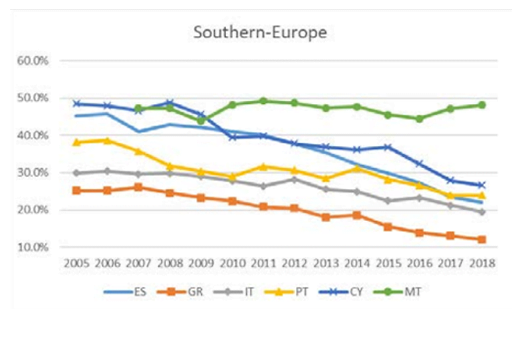

There’s an equally significant change in the percentage of owner-occupied households amongst young people. In the following graph, we can clearly see the shrinkage in the number of 25-34 year-olds who own a house in Southern European countries, with Greece always in last place, with quite a distance from the rest. This tendency is rather horizontal in Europe, with only 5 countries showing signs of an increase in the percentage of home ownership, most of which are in Eastern Europe. This delayed access to owner-occupied property is linked to three factors: a) the worsening labour markets, b) the welfare reforms that have cut huge holes in the existing safety net, especially for young people who don’t have steady employment histories, and c) the increase in property prices due to the fact that housing and mortgages are more and more so seen as a financial asset. 11.

Graph 3. Owner-occupied property percentage amongst young people aged 25-34 in Southern Europe. 12

But what about people between the ages of 35 and 44? Unfortunately, there’s no relevant data for Greece, but we have a report by the British Office for National Statistics that contains some data that could give us a useful insight. According to this report, people of this particular age group are three times more likely to be living in rented property, than people their age were, 20 years ago. Another British study 13, concludes that less than 50% of millennials will become home-owners before the age of 45, and that one in three millennials will never own a house 14.

The above findings have led many researchers to call people of that age either “Generation Rent” or “Boomerang Kids”.

In order to better understand the reasons behind this, we’ll analyse certain data that will help us better understand the significant changes that have affected the Greek families ability to meet the current circumstances.

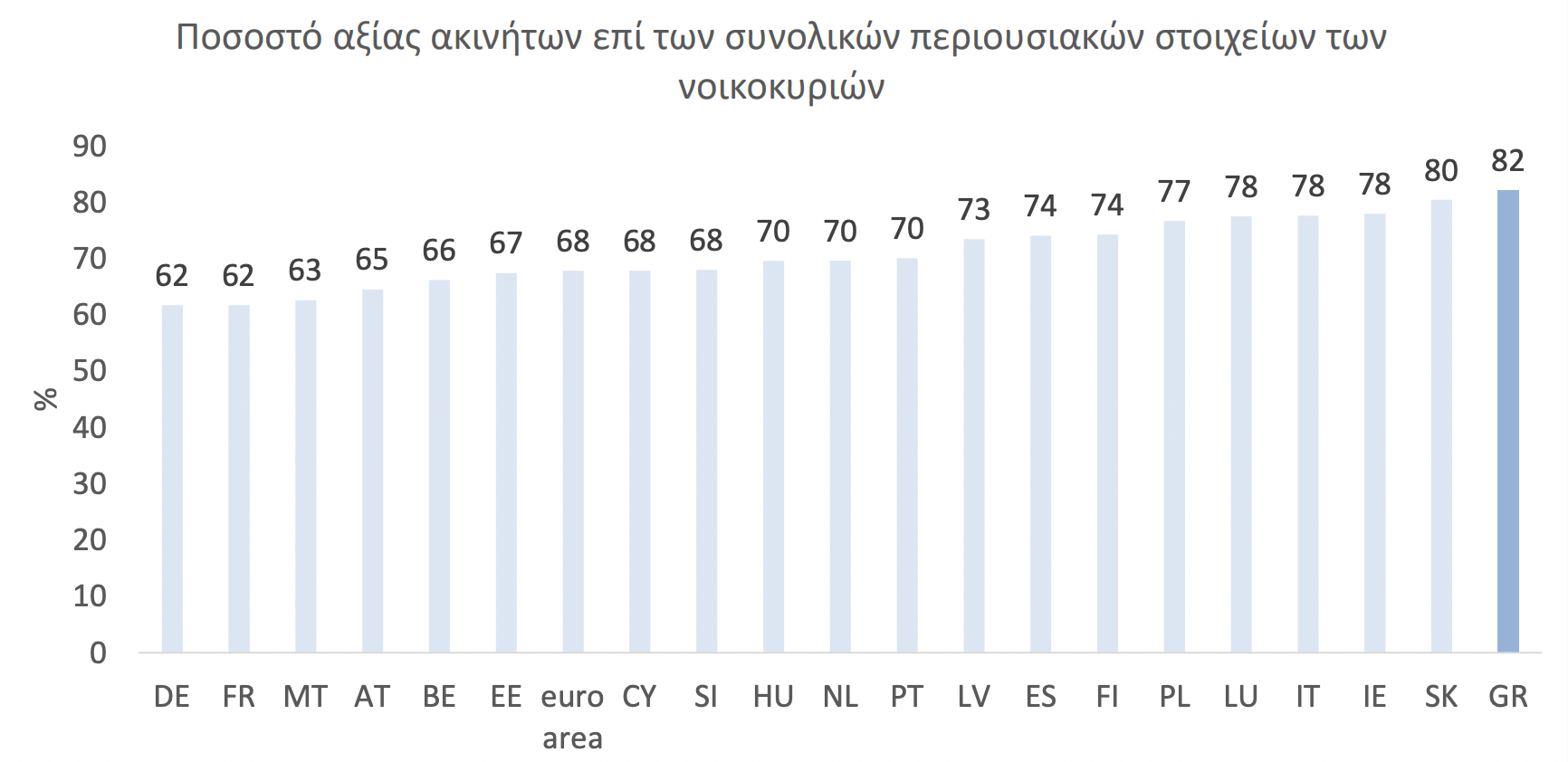

Graph 4. Real estate holdings make up 82% of an average Greece household’s overall assets. Approximately ⅔ are the household’s main residence and the other ⅓ is other real estate properties 15. According to the Hellenic Statistical Authority, in 2018, 14,9% of Greek households owned a 2nd house – a 16,3% drop since 2008. 16

Through the years, in Greece there have always been two main available options in order for one to own a house: Either by capitalising on family property or by getting a mortgage, with the family’s monetary support being an important factor in both cases. In a research conducted in 2013, D. Emmanuel found that 37,8% of home-owners acquired their house through inheritance or parental grant, 30,3% by getting a mortgage and 17,5% without needing a mortgage. But if we take into account other forms of family support, such as cash donations, the percentage of people who were able to buy a house partly thanks to family related aids rises to 56,4% of the total 17.

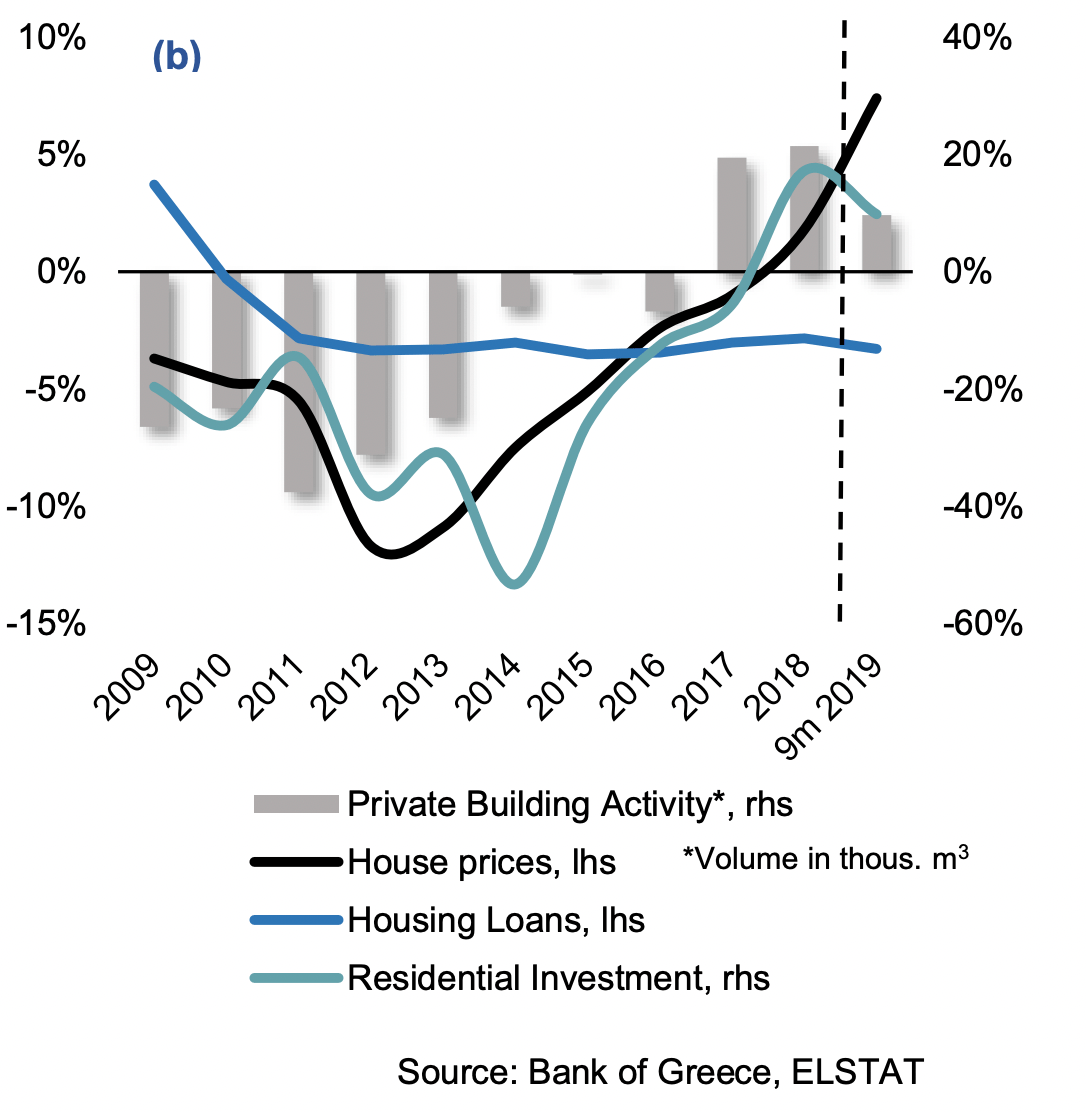

Yet, the Greek economy has undergone and actually is still battling with a lengthy financial crisis that has led to the shrinkage of the Greek family’s assets and thus is directly affecting its strategic decisions regarding the way the family members cover their housing needs. The following graph shows how the rise in house prices falls in line with the tendency noted in residential investments and the increase in private building activity. On the other hand, the mortgage market shows no raising tendency, and remains negative since 2010, thus triggering a credit-less recovery, according to Alpha Bank’s report.

Graph 5. House prices, housing loans, residential investment and private building activity in Greece, 2009-2019 18.

Therefore, according to the same report, said recovery is linked to the significant increase of foreign investments in the real estate market. This is confirmed by the annual real estate market overview by Delfi Partners 19, that refers to this recovery as “exogenous”. Maloutas, Siatitsa and Balabanidis 20, concur and estimate that 75% of new transactions in the undervalued Greek real estate market involve foreign buyers.

Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that the vivid presence of foreign investors in Greece’s real estate market, doesn’t mean that the local presence has died out. A very informative study regarding changes in property ownership in the area of Exarcheia in 2009-2018, shows that the grand majority of the buyers were Greek (70,9%) (foreign nationals 14,6% and legal persons 14,5%). Yet, in recent years there has been a visible change: While back at the beginning of the recession, in 2009, foreign investment represented only 5,2% of the real estate market, in 2018, it rises to 42,5% of real estate buying by natural persons 21.

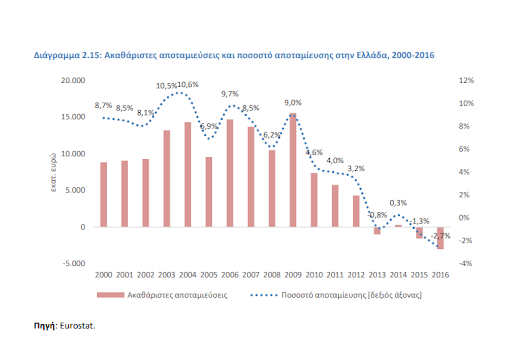

In such an environment, the Greek family plays an increasingly important role, since its younger members have extremely limited capacity to secure their own home. On the other hand, the Greek family’s ability to cover the housing needs of its members has significantly decreased in the past decade. A first indicator would be the available household income in Greece that has shrunk by 33% in 2008-2016. A second indicator are the gross savings and the savings percentage, which, as we can see in the graph below, have been in constant decrease in the past decade 22. According to the The Bank of Greece Interim Report on Monetary Policy 2021 23, the savings percentage has risen above zero in the past 3 years but still, as per the same report, “despite projections for a slower increase in goods’ prices in 2022, the inflation rise has already affected the households’ spending income and are raising concerns regarding their temporary or permanent nature”.

Graph 6. Gross savings and savings percentage in Greece, 2000-2016 24.

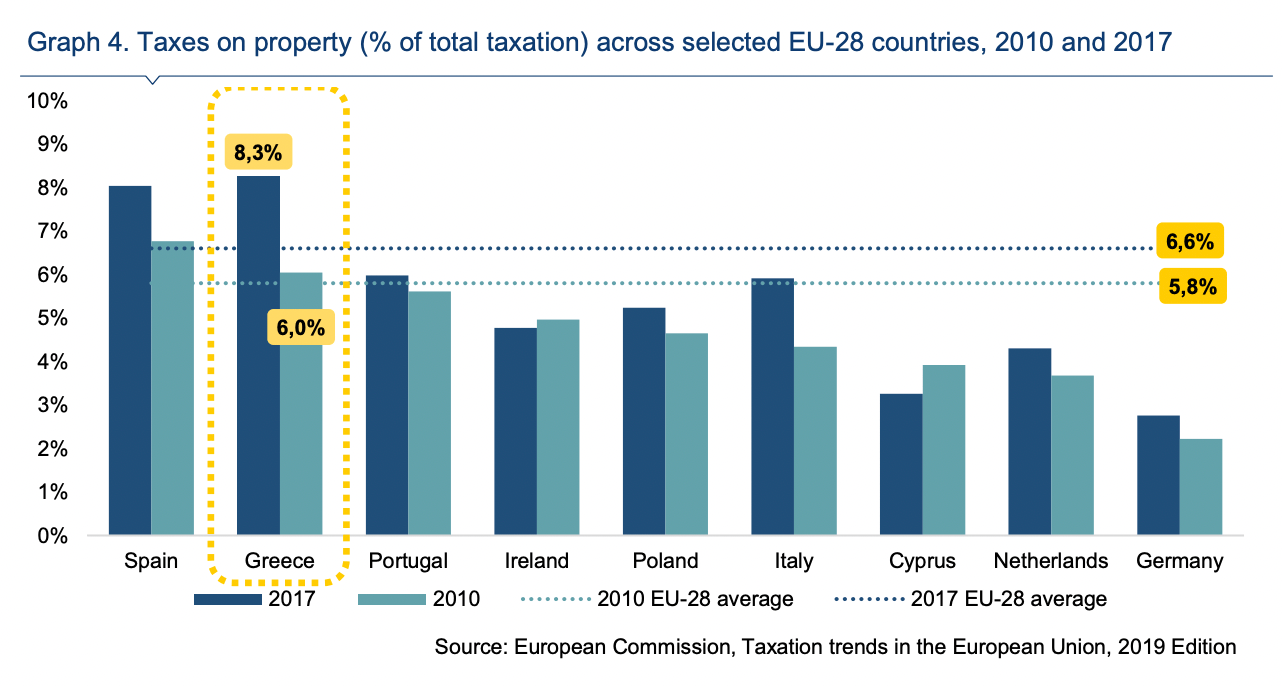

Another factor to consider is the increase in property taxing, mainly through the Unified Property Ownership Tax (UNPOT or ENFIA in Greek) that was imposed in January 2014. With its implementation, property tax increased sixfold (from 500 million it raised to 3 billion) 25 and according to the IOBE report 26, those taxes are “a heavier burden for lower income households – mainly those with an income of up to 5000 Euros, as they absorb 15,5% of this category’s available income”.

Graph 7. Comparison of taxes on property in EU countries 27.

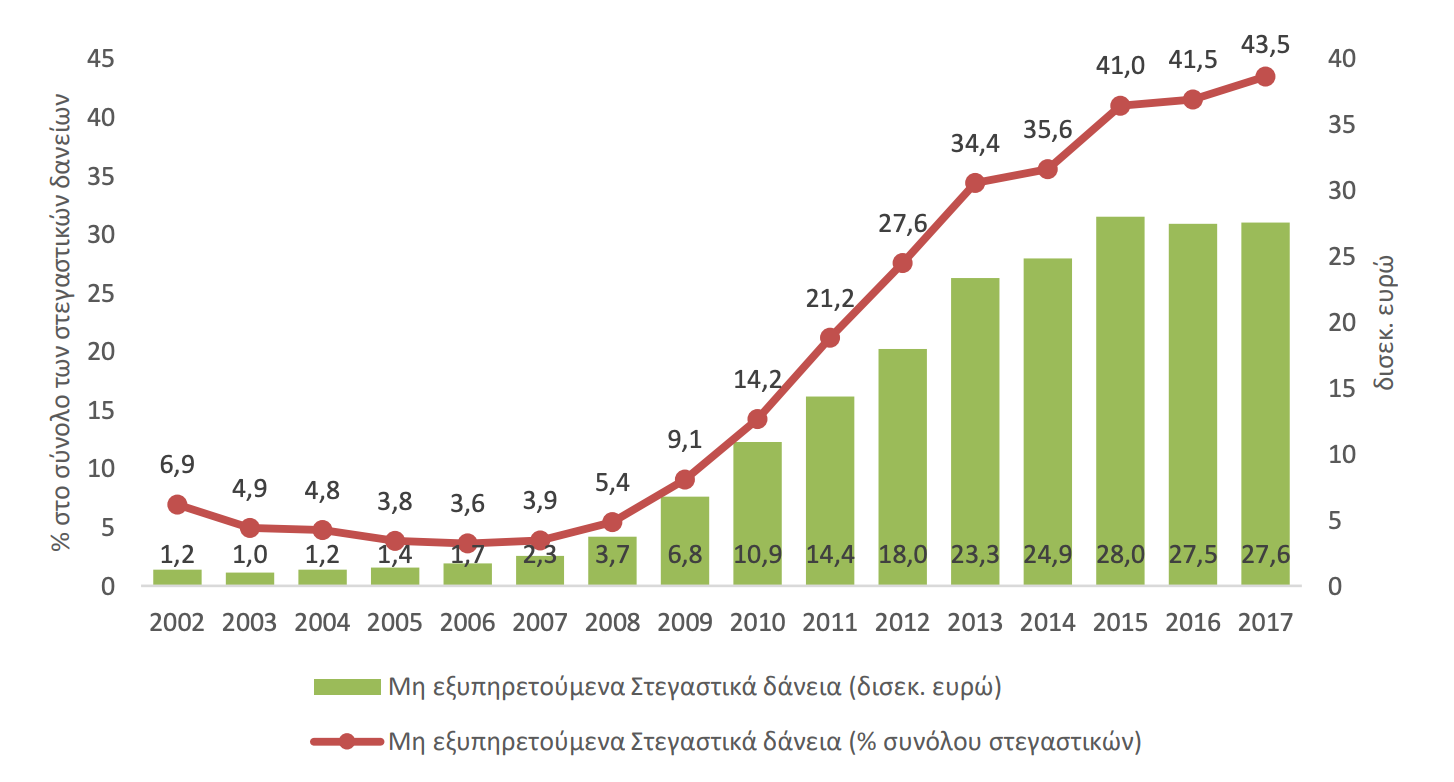

The last factor that affects the average Greek family’s capacity to function as the main driving force with regards to the housing issue, is access to bank loans that have been the predominant option in Greece prior to the financial crisis. In 2001-2008 mortgages in Greece went up by 600% 28. When the recession hit the country, an increasing number of Greek households were no longer able to pay their increased mortgage installments, with non-performing loans reaching 43,5% of the total of given mortgages in 2017 29.

Graph 8. The course of non-performing mortgages in Greece 2002-2017 30.

Because of their non-performing mortgages, many Greek households have faced the menace of property foreclosure. According to iMedD Lab’s application that monitors the auction process throughout each year, there have been 47,200 auctions since 2018, 11,014 of which were house foreclosures (32,4%). At this point, we should note that just because an auction was performed, doesn’t necessarily mean that it was fruitful. Therefore, the number of properties that changed ownership is significantly smaller than the above.

All the above lead to the conclusion that Greek society is going through an important, if not fundamental, change of the way it covers its housing needs.

In his 2014 article, D. Emmanuel 31 makes a daring prediction regarding the future of the housing issue in Greece: “the general home ownership rate will most probably decrease by a substantial margin given the squeeze on savings and the shift in affordability conditions while the extend of class inequalities in access to ownership, given the removal of existing working class housing assistance and the new sharp inequalities in unemployment and labor market conditions, will certainly increase. But, unless an onslaught on small property of proportions akin to historical cases of “primitive accumulation” takes place, the overall pattern will continue to be a case of the traditional southern regime, albeit a sharply modified one – an impoverished and more unequal pattern.” Seven years later, judging by the research above, one feels that the prediction was spot on – at least to a large extent.

All this raises the next question which is “who are the people on the lower scales of this housing inequality and who are having a hard time securing access to adequate housing?”. It is the people whose financial and social independence has been and still is going through the dire straights of the economic recession. Those who don’t have a secure steady job and sufficient income. People whose families have lost a large part of their wealth and therefore can’t support their younger members in their housing pathway, at least not to a substantial degree. Those for whom the renting cost is a heavy burden and each increase brings them closer to the poverty line. It is people aged 25-40+ whose housing pathway seems to have deviated significantly from the one taken by the previous generations.

The ever increasing rents, place all those who are living in rented housing in a very precarious situation.

A further increase in renting costs, combined with the huge inflation of the electricity and heating bills that households are already experiencing, will most likely form new conditions of insecurity, inequality and exclusion.

How is the State conspicuously absent from the matter, leading several experts to comment that in a way, “lack of policy in itself is a policy”? How has short-term lease created conditions that heighten the inequality between the landlords and those in need of housing? How is housing and the city itself becoming investment products and how does that affect the average citizen?

All of those are major issues that directly or indirectly affect access to adequate and affordable housing for many amongst us. We couldn’t possibly answer all of those questions in one single article. In the following weeks, we’ll follow up with posts containing analysis of the issues raised above, hoping to shed some light on a matter that affects many of our co-citizens, the average Greek family and Greek society in general.

Alkis Kafetzis is the Coordinator of the Project “Sky-high rents | Housing insecurity today”

Notes

- Alpha Bank Economic Research, ‘The rise, fall and revival of the residential property market in Greece: Bringing new drivers of house price fluctuations to the foreground’, 2020, 1[↩]

- RΕ/MΑΧ, ‘Greek Rental Housing Survey’, 2017, 2018 και 2021 (in Greek) [↩]

- Alpha Bank Economic Research, ‘The rise, fall and revival of the residential property market in Greece: Bringing new drivers of house price fluctuations to the foreground’, 2020, 9[↩]

- Aris Sapounakis, Eleni Komninou, “The question of evictions in Greece”, in ‘Housing and Society: Problems, Policies and Movements”, Athens, Dionicos, 2019: pp. 77-96 (in Greek) and Dimitra Siatitsa “Anyone at home? Housing in Greece: The Impact of Austerity and Prospects for the Future”, Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung Greek Office, 2019: 28), [↩]

- Eurostat, ‘Housing cost overburden rate, analysed by tenure status’, 2019[↩]

- Dimitra Siatitsa, ‘Youth Housing in a Context of Socio-economic Insecurity: The Case of Greece’, Social Policy: 14: 149–62. and Dimitris Emmanuel, ‘Social aspects of access to home ownership’, Athens Social Atlas, 2015[↩]

- Caroline Dewilde, ‘Exploring Young Europeans’ Homeownership Opportunities’, Critical Housing Analysis 7, 1: 86–102[↩]

- Dimitra Siatitsa, ‘Youth Housing in a Context of Socio-economic Insecurity: The Case of Greece’, Social Policy: 14: 153[↩]

- Dimitra Siatitsa, ‘Youth Housing in a Context of Socio-economic Insecurity: The Case of Greece’, Social Policy: 14: 152 Dimitra Siatitsa “Anyone at home? Housing in Greece: The Impact of Austerity and Prospects for the Future”, Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung Greek Office, 2019: 31[↩]

- Dimitra Siatitsa, ‘Youth Housing in a Context of Socio-economic Insecurity: The Case of Greece’, Social Policy 14: 153[↩]

- Caroline Dewilde, ‘Exploring Young Europeans’ Homeownership Opportunities’, Critical Housing Analysis 7, 1[↩]

- Caroline Dewilde, ‘Exploring Young Europeans’ Homeownership Opportunities’, Critical Housing Analysis 7, 1: 92[↩]

- Adam Corlett και Lindsay Judge, ‘Home affront: housing across generations’ (Resolution Foundation, 2018[↩]

- Patrick Collinson, “One in three UK millennials will never own a home – report“, The Guardian, 2018[↩]

- Foundation for Economic & Industrial Research (IOBE), ‘Real estate taxation and the future of construction in Greece’, 2018: 102 (in Greek) [↩]

- ELSTAT, Living Conditions in Greece, 2020[↩]

- Dimitris Emmanouel, ‘The Greek System of Home Ownership and the Post-2008 Crisis in Athens’, Region et Development, τχ. 39 (2014): 174[↩]

- Alpha Bank Economic Research, ‘The rise, fall and revival of the residential property market in Greece: Bringing new drivers of house price fluctuations to the foreground’, 2020: 16[↩]

- Delfi Partners & Co., ‘Real Estate Market Overview: Greece’, 2020: 9[↩]

- Thomas Maloutas, Dimitra Siatitsa, και Dimitris Balampanidis, ‘Access to Housing and Social Inclusion in a Post-Crisis Era: Contextualizing Recent Trends in the City of Athens’, Social Inclusion 8, 3: 5–15[↩]

- Giorgos Lialios, ‘Property transformations in the centre of Athens during the economic crisis years (2009-2018). The case of Exarcheia’, Athens Social Atlas, 2021[↩]

- Foundation for Economic & Industrial Research (IOBE), ‘Real estate taxation and the future of construction in Greece’, 2018: 102 (in Greek) [↩]

- Bank of Greece, ‘Monetary Policy Interim Report, 2021, 47 (in Greek) [↩]

- Foundation for Economic & Industrial Research (IOBE), ‘Real estate taxation and the future of construction in Greece’, 2018: 29 (in Greek) [↩]

- Thomas Maloutas, Dimitra Siatitsa, και Dimitris Balampanidis, ‘Access to Housing and Social Inclusion in a Post-Crisis Era: Contextualizing Recent Trends in the City of Athens’, Social Inclusion 8, 3: 9[↩]

- Foundation for Economic & Industrial Research (IOBE), ‘Real estate taxation and the future of construction in Greece’, 2018: 85 (in Greek) [↩]

- Alpha Bank Economic Research, ‘The rise, fall and revival of the residential property market in Greece: Bringing new drivers of house price fluctuations to the foreground’, 2020: 7[↩]

- Antonis Varkas, Konstantinos Komineas, Charalambos Mertis, ‘The mortgage arrears and the changing of the model for housing in Greece today’ (Lecture in National Technical University of Athens, 2015: 37 (in Greek) [↩]

- Foundation for Economic & Industrial Research (IOBE), ‘Real estate taxation and the future of construction in Greece’, 2018: 35-37 (in Greek) [↩]

- Foundation for Economic & Industrial Research (IOBE), ‘Real estate taxation and the future of construction in Greece’, 2018: 35-37 (in Greek) [↩]

- Dimitris Emmanouel, ‘The Greek System of Home Ownership and the Post-2008 Crisis in Athens’, Region et Development, τχ. 39 (2014): 180 [↩]