Energy poverty, housing and policy tools: Reproducing inequality

In a previous Eteron analysis on housing, we attempted to examine the changes that have occurred over the course of the past few decades in the way Greek society meets its housing needs. Through a number of statistical graphs it (hopefully) became apparent that the gap between those who can follow the market’s dictates and those who cannot, is widening.

In recent months, as energy prices have soared, households have been facing a looming crisis. While plenty of data has emerged to illustrate the ramp-up in energy cost increases,1 it is not sufficient for a deeper understanding of the true magnitude of the problem. Much has been written about the causes of rising energy costs for households, mainly covering the problems on the supply side. But little has been said about the demand side, i.e. consumption. In the present analysis we revisit the issue of housing inequalities, but this time seen through the lens of energy, i.e. a household’s ability to adequately heat its home. In this paper we look not only at the issue of energy poverty, but also at that of policy tools such as the “Energy Saving at Home” programme (“Exoikonomo”) and how they can potentially contribute to the reproduction of these inequalities.

Is the energy crisis “just” a result of the international price spike? Is the state making efforts, as it should, to effectively lift society out of the maelstrom of poverty, which in this case is energy-related? Are the huge financial opportunities, due to European funding, leading to long-term solutions to the country’s structural problems or are they, as usual, acting as a carpet under which we’ll sweep our problems? In other words, are we developing conditions that would allow us to become more resilient as a society in the face of an ever-changing and unstable environment?

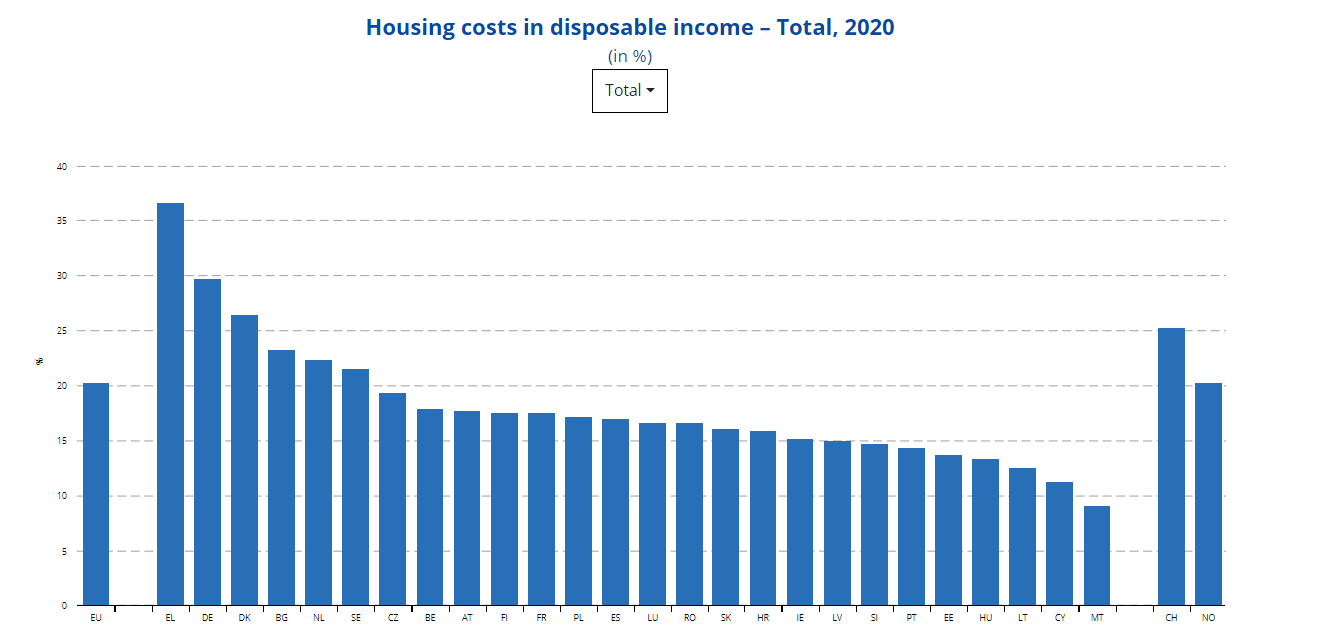

Graph 1. Housing costs in disposable income. Total 2020. Greece is in first place (Eurostat)

At a time when housing costs (the sum of rent or mortgage instalments plus utility bills and communal charges) are on a continuous rise, the discussion on the amounts households pay for electricity bills should explore both the reasons why we need so much energy as well as the ways in which this burden is shared between different parts of society. There is some data that can help us gain a better insight of this situation.

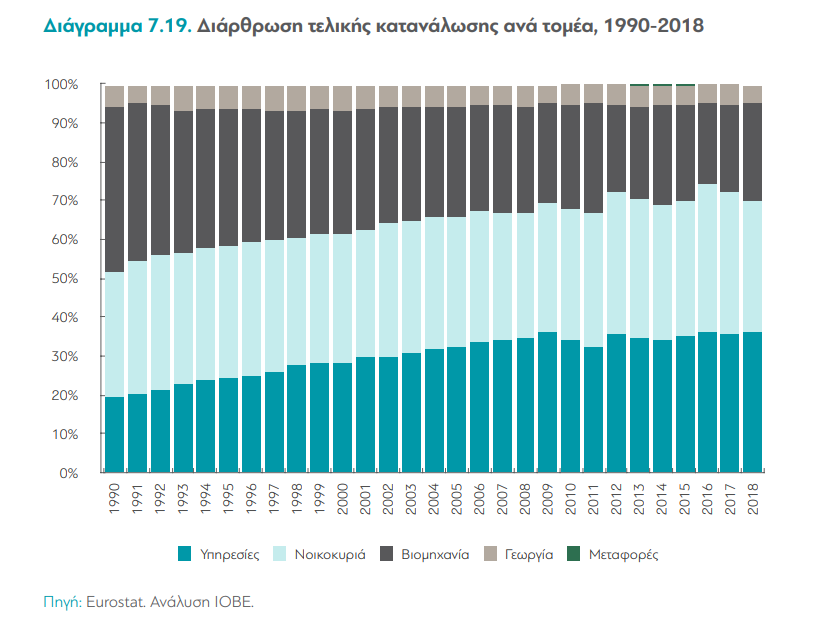

According to the Ministry of Environment and Energy’s long-term strategy for the renovation of the Greek building stock published in the Official Government Gazette in March 2021, approximately 40% 2 of the final electricity consumption in Greece is due to building uses, with residential buildings representing 95.4% of the total building stock. A report on the Energy Sector in Greece published in April 2021 by the Foundation for Economic & Industrial Research (IOBE) and Dianeosis reached a similar conclusion, stating that the residential sector accounted for 32.8% of final electricity consumption in 2018, second only to the services sector, which was calculated at 34.9%.

Graph 2. Residential buildings represent 30-40% of final energy consumption in Greece in the past decades, page 206, IOBE – Dianeosis report (report available in Greek here)

[DIAGRAM 7.19 Breakdown of final consumption per sector, 1990-2018// Services/ Households/ Industry/ Agriculture/ Shipping-Transportation]

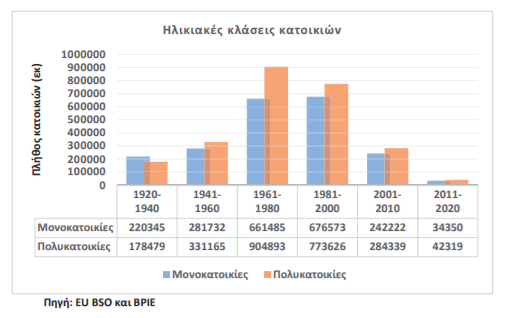

The following graph, extracted from the above-mentioned Ministry of Environment and Energy (YPEN) strategy plan, clearly depicts the Greek residential building stock’s age. As mentioned in the Ministry’s strategy report, “Over half of the residential houses in the country (55.7%) were built before the 1980s, that is prior to the implementation of the Buildings’ Thermal Insulation Regulation, and therefore do not include thermal insulation, thermal protection and appropriate thermal bridging”. Out of the remaining 44.3%, “42.7% were built until 2010 and therefore only had to have partial thermal insulation systems installed, and only 1.6% were built after 2010, that is after the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive was implemented”.

Graph 3. The age of Greece’s residential buildings stock. Page 13, YPEN

[Dwellings age/ Number of dwellings/ Single-storey houses/ Apartment blocks]

Since 2010, it is mandatory to issue an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC), a tool that provides a more detailed overview of the state of the country’s housing stock. Again according to YPEN’s strategy plan, the issued EPCs mainly concern buildings constructed until 2009, while 88.3% are for buildings (mainly apartments) to be rented and/or sold. The vast majority of these buildings (66.63%) are classified in the lower energy efficiency categories E-H, while the largest share of energy is consumed mainly for heating needs.

Therefore, it should come as no surprise that even before the current spike in electricity and heating costs, 26% of households stated they couldn’t afford to pay for sufficient heating during the winter, while 13.6% of households said they live in homes with leaking roofs, damp walls, floor and foundations, or in flats with rotting window frames and/ or floors (Anyone at home 2019 Siatitsa, pages 23-25). The corresponding percentages amongst poorest households in 2020 were 39.1% and 20.2%, while for the overall population they were 17.1% and 12.5% (Hellenic Statistical Authority, Press Release: Material Deprivation and Living Conditions, Sept ‘21).

The question that arises after all this, is whether the necessary mechanisms exist in order to tackle the particularly widespread issue of energy poverty and whether such mechanisms mitigate or exacerbate inequalities within Greek society.

In response to rising energy prices and to the resulting pressure on household budgets, the public debate has so far been concentrated on subsidy measures. Thus, according to YPEN’s announcement on 9 February (available in Greek here), the state has allocated more than 2 billion Euro since September 2021 “in order to support the people who are affected by the major energy price increases”. However, while such measures are certainly palliative while they last, they do not address the source of the problem. In the same statement, YPEN speaks of the need for a permanent reduction in consumption, which will eventually lead to a permanent reduction in electricity/ energy bills. The main tool that Greece has at the moment in order to achieve this goal is the “Energy Saving at Home” programme (“Exoikonomo”).

The main funding scheme contributing to the implementation of the organised effort to reduce energy consumption is the “National Recovery and Resilience Plan, Greece 2.0”. By 2025, 3.1 billion Euro are expected to be invested in energy efficiency upgrades for residential buildings throughout Greece, of which 1.6 billion Euro will be provided in the form of subsidies.

There is already considerable criticism as to the programme’s ambition and scope. Greenpeace Greece, for example, issued a statement (available here in Greek) over a year ago stressing the fact that the goal of tackling climate crisis and energy poverty can only be achieved if the total funding for a complete energy upgrade of 150,000 homes per year reaches 50 billion in a 30 year span.

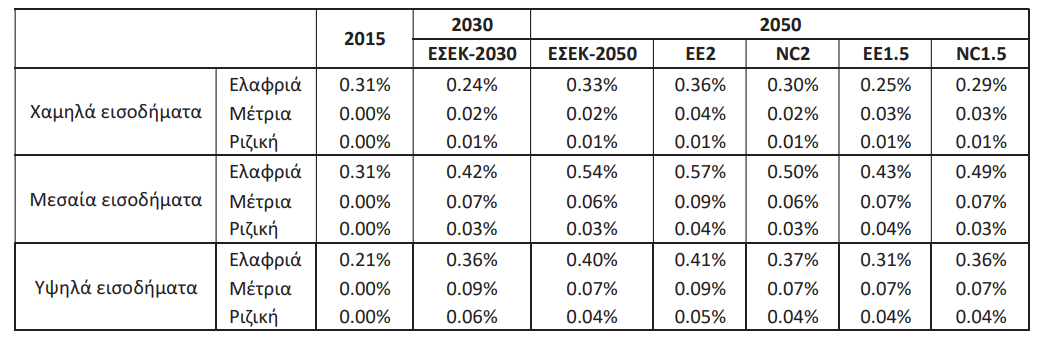

Graph 4. Average annual building envelope upgrade rate per intervention type for 3 income tiers, based on goals outlined in the National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) for 2030, the NECP for 2050 and 4 more possible outcomes designed to keep the temperature rise at 1.5 – 20C plus two different strategic plans to reach those goals: that of the EU or NC (YPEN, 2021, page 46)

[2015/2030/2050// NECP-2030/ NECP-2050/ EU2/ NC2/ EU 1.5/ NC 1.5// Low income/ middle income/ high income// minor/ moderate/ major]

However, the assessment of some qualitative features of the existing home energy upgrade programme raises further questions as to whether this particular and very important opportunity will lead to substantial results. After dividing energy upgrades into three types: a) minor (window frames), b) moderate (window frames, envelope insulation, roof) and c) more radical renovations, YPEN’s long-term strategy calculates the average annual rate of each type of intervention for 3 different income tiers (Graph 4).

Based on these estimates, YPEN’s strategy draws some significant conclusions: “Across all income groups, the most common renovations’ rate will be minor, but still, in the middle and high income groups, the interventions will be more intensive. In the low income groups, the corresponding rate of moderate and major renovation will remain particularly low given the high cost of the necessary materials and equipment – a cost that would require a large proportion of the households’ total disposable income and therefore makes such interventions unaffordable without the provision of financial incentives and concessions […] The provision of income-based subsidies to finance renovations can be a tool for implementing more major interventions in the homes of low-income households”.

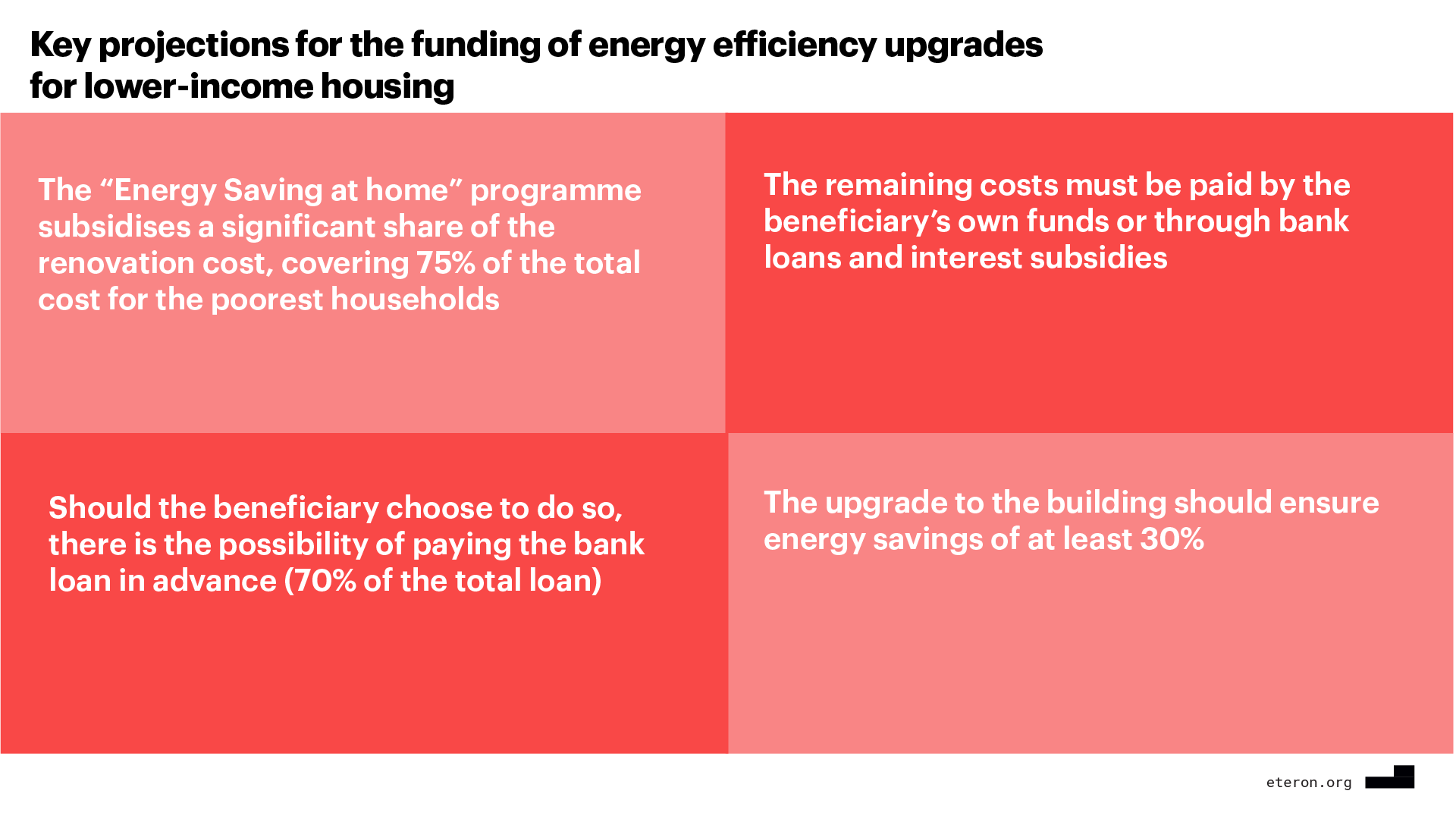

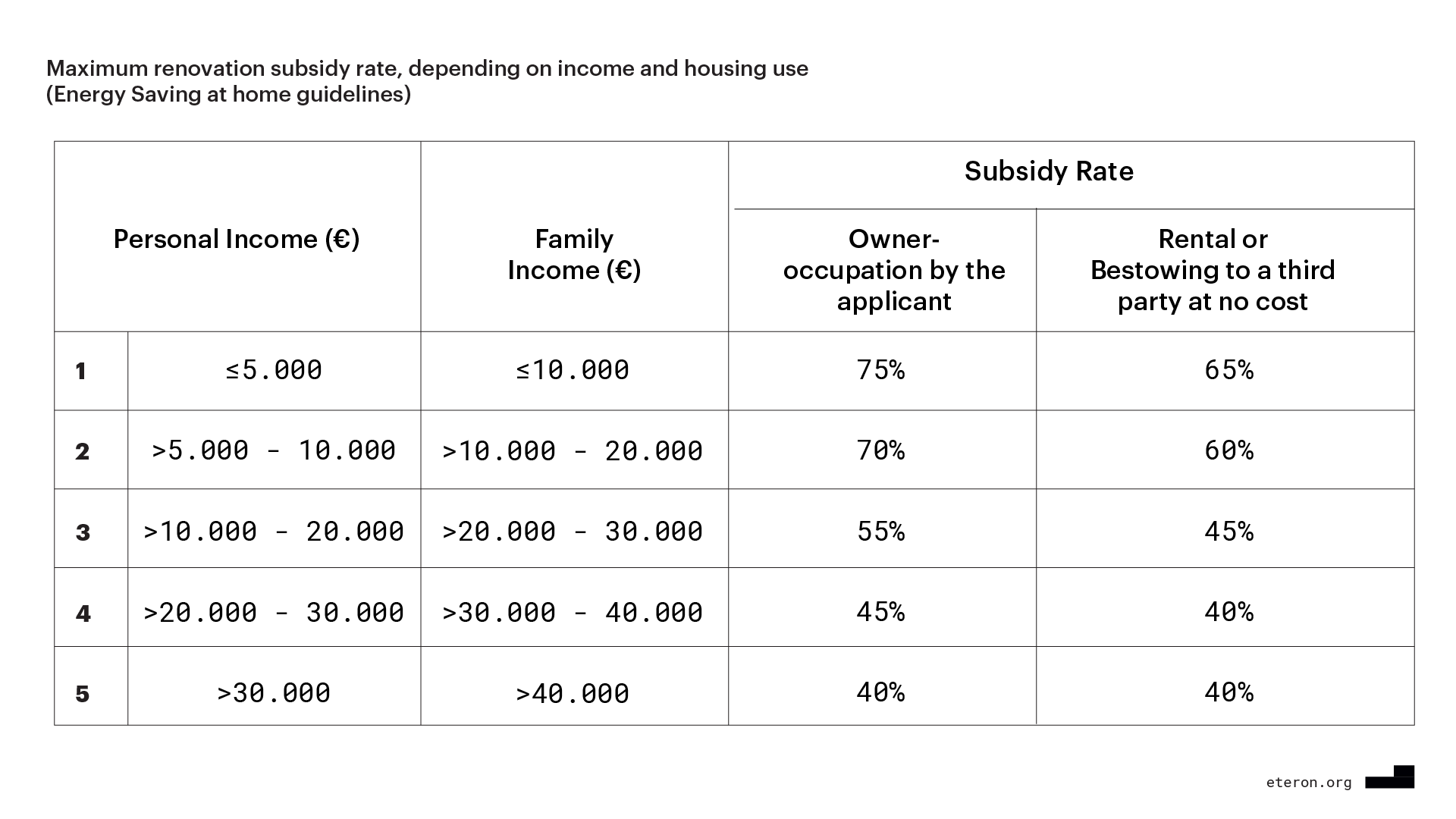

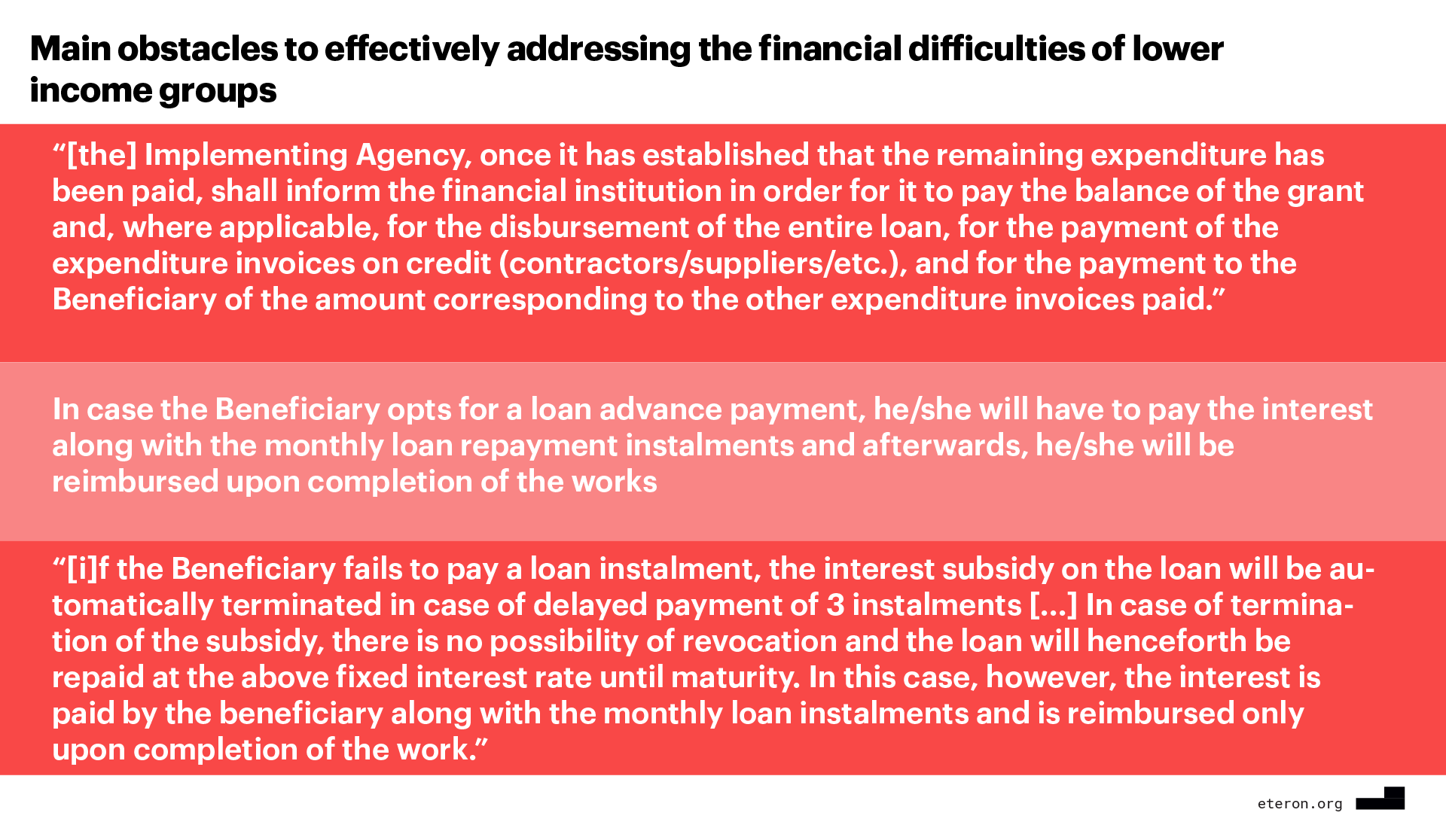

Therefore, the value of the most extensive building renovation programme in the country, in terms of social cohesion and mitigating inequalities, depends directly on the lower income groups’ access to funding schemes. Looking at the data in the following graph, it appears that the necessary tools are in place that would ensure the lower income households’ access to funding for this particular programme – a fact that could lead to the reduction of energy poverty horizontally within the Greek society. However, once again, appearances seem to be deceiving, as in order for the lower-income households to be able to participate in the programme, they need to have a significant capital readily available.

Sources: “Energy Saving at home”, “Implementation guidelines for the ‘Energy Saving at home’ programme”, Piraeus Bank, “Energy Saving at home” programme, Eurobank, Energy Saving at home programme 2021

How big a problem can this seemingly small deficiency create? Can’t poorer households secure a few thousand euros to invest in their home? According to people we spoke to who are directly involved in the “Energy Saving at Home” programme and the housing energy upgrade sector, this seemingly small problem has already caused significant distortions in the market. This is because often the contractors and suppliers who undertake the renovation projects are also the ones who take on the debts, of course at a premium, which usually means overcharging for the work. Hence especially in the case of lower income groups, these distortions significantly reduce the return on the money invested.

Persistent energy poverty helps us get a better understanding of the issue of poverty within Greek society, seen through the perspective of the housing issue and the way the state deals with the increasingly entrenched social inequalities. “We have reached a point where people believe,” says one of the people interviewed for Eteron’s early videos, “that heating is a luxury. It’s not a luxury!”

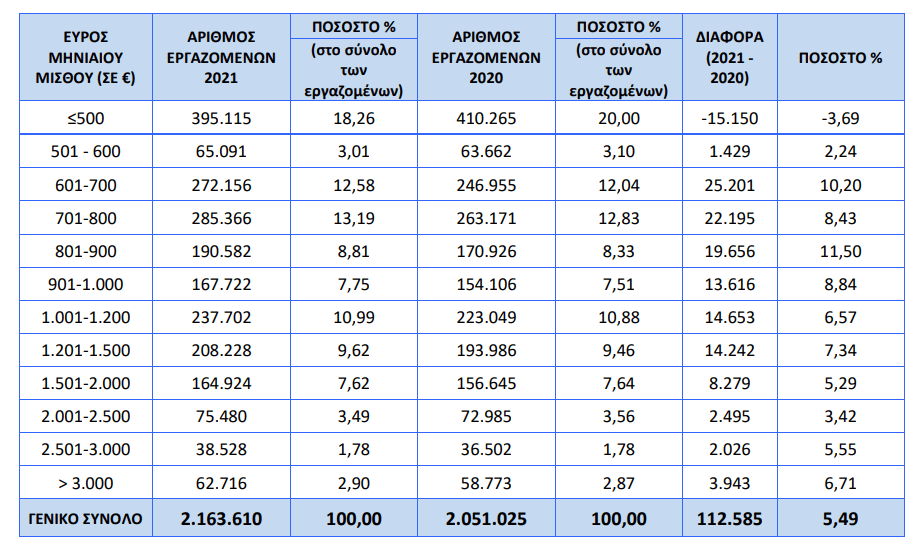

If we look at the data available at the Ergani information system regarding the number of employees per monthly salary range (Graph 6), the image gets increasingly bleeker. According to the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs’ information system, 33.8% of the employees in Greece earn less than 700 Euro per month. In other words, 732,381 people fall into the first two income categories of the “Energy Saving at Home” programme (under the condition that they receive 14 salaries per year)3. It is of course questionable whether people who earn even 1000 Euro per month can meet the requirements of “Energy Saving at Home” or heat their homes efficiently.

Graph 6. Number of employees per monthly salary range.

Ergani special issue, 2022 (page 13 – available in Greek here)

[MONTHLY SALARY RANGE (IN EUR)/ NUMBER OF EMPLOYEES 2021/ PERCENTAGE % (OUT OF THE TOTAL NUMBER OF EMPLOYEES/ NUMBER OF EMPLOYEES 2020/ PERCENTAGE % (OUT OF THE TOTAL NUMBER OF EMPLOYEES/ DIFFERENCE (2021-2020)/ PERCENTAGE %)

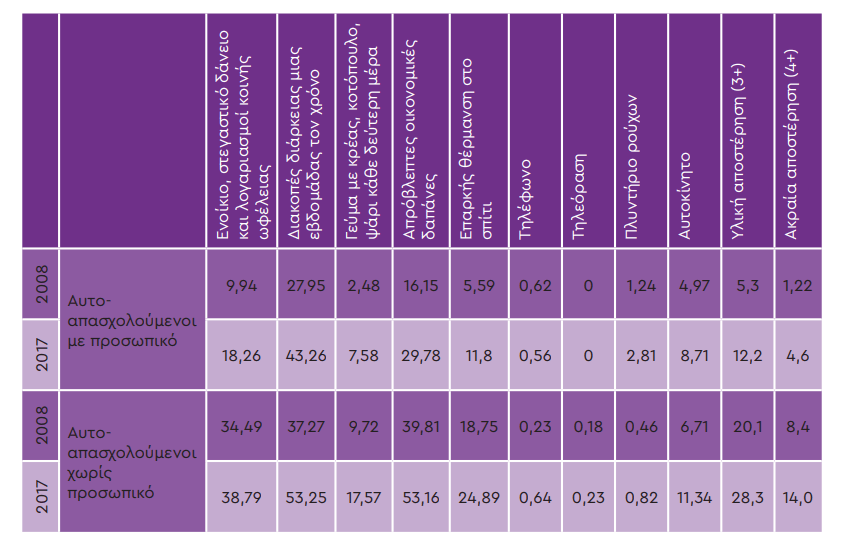

Employees aren’t the only group that’s having a hard time. A survey (2021) conducted by The Small Enterprises’ Institute and the Hellenic Confederation of Professionals, Craftsmen, and Merchants (IME-GSEVEE – available in Greek here) clearly reflects a similar situation in the self-employed sector. As shown in the table below, a significant proportion of self-employed persons without personnel were unable in 2017 to cover their housing costs (38.79%) and to adequately heat their home (24.89%). Finally, according to the same study, “the average disposable income of self-employed persons without personnel is at a similar level to the corresponding average income of the total population of the country”, i.e. just over 9000 Euro per year.

Graph 7. Material and severe material deprivation by subgroup of self-employed persons (page 90)

[Self-employed persons with personnel/ Self employed persons without personnel // Rent, mortgage payment plus utility bills/ One-week holidays per year/ Meal containing meat, chicken, fish once every two days/ Unforeseen expenses/ Adequate heating at home/ Home/ TV/ Washing Machine/ Car/ Material deprivation/ Severe material deprivation]

Moreover, all of the above is happening at a time when the income of Greek society is under even greater pressure due to significant revaluations. The data published by the Labour Institute of the General Confederation of Greek Workers (GSEE) in January ‘22 are revealing and indicative of the situation. According to the Economic Trends Bulletin (page 3 – available in Greek here), “Expensiveness, purchasing power and the labour market”, between December 2020 and December 2021, the purchasing power loss of the minimum wage, the average monthly individual disposable household income and the average wage of the part-time employees is 10.4%, 6.9% and 13.7% respectively.

At the same time, it is becoming increasingly clear that we are living in a time of increasingly changing circumstances. Energy poverty is a prime example. While we all approach it as an issue that relates exclusively to the winter season, the climate crisis is increasingly bringing “summer energy poverty” to the fore. Just a few months ago, we were all experiencing a particularly warm and dry summer and, according to a research conducted by Dianeosis in October 2021 (English summary available here or you can read the full research in Greek here), the number of hot days in the Athens’ city centre is expected to quadruple even in the best case scenario. As it was very eloquently stated in the City of Athens’ Climate Action Plan (2017 – page 8) “Electricity use in Athens increases 4.1% for every 1°C increase in temperature, costing residents and businesses hundreds of Euros in higher energy bills.”

It is clear that society needs a set of support measures that will allow it to face the uncertain future with more confidence. For the time being, it seems that the state is moving ahead with initiatives that are more of a palliative nature, without grasping the magnitude of the problem. As a result, Greek society remains effectively naked in the face of such risks.

References

- City of Athens, Climate Action Plan, 2017 (in Greek – executive summary in English)

- Dianeosis, “The Consequences Of Climate Change In Greece”, 2021 (full research in Greek available here)

- Eurobank, Energy Saving at home programme 2021, accessed on 15th March 2022

- Eurostat, ‘Is housing affordable?’, accessed on 15th March 2022

- Fameliari Sandy and Gregoriou Takis “Is it time to revisit tax incentives for housing energy upgrades?”, Greenpeace, 2021 (in Greek)

- Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT) , Consumer Price Index: January 2022, inflation rate 6.2%, 2022

- Hellenic Statistical Authority, Press Release: Material Deprivation and Living Conditions, 2021

- Independent Power Transmission Operator (IPTO or ADMIE in Greek) , weighted average electricity price, accessed on 23rd February 2022

- Kitchen Carl and Wang Blaine, ‘International electricity prices: how does Australia compare?’, Australian Energy Council, 2022, accessed on 15th March 2022

- Labour Institute of the General Confederation of Greek Workers (INE-GSEE), “Economic Trends Bulletin: “Expensiveness, purchasing power and the labour market”, 2022 (in Greek)

- Ministry of Environment and Energy (YPEN), ‘Kostas Skrekas: 350 million Euro to be dispensed in February in order to support households and businesses’ (in Greek)

- Ministry of Environment and Energy (YPEN), “Approval of the report of the mid-term strategy plan to renovate the public and private buildings’ stock, in order to lower CO2 emissions and improve energy efficiency by 2050, as per paragraph 2 of article 2A, Law 4122/2013” Official Government Gazette Issue 974/2021 (in Greek)

- Ministry of Environment and Energy (YPEN), “Energy Saving at home”, accessed on 15th March 2022 (in Greek)

- Ministry of Environment and Energy (YPEN), “Implementation guidelines for the ‘Energy Saving at home’ programme”, 2022 (in Greek), 2022

- Ministry of Finance, Greece 2.0 – National Recovery and Resilience Plan, accessed on 15th March 2022

- Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, “Special annual publication: results of the electronic registration of the total sum of businesses and employees of the private sector from 1st October till 30th November 2021”, 2021 (in Greek)

- Papatheodorou Christos, Missos Vlasis, Papanastasiou Stefanos, “A study on the effects of the economic recess on the income and living conditions of small business owners and self-employed individuals: new types of inequalities, poverty risk and the role of the welfare state”, The Small Enterprises’ Institute and the

- Hellenic Confederation of Professionals, Craftsmen, and Merchants (IME-GSEVEE), 2021 (in Greek)

- Piraeus Bank, “Energy Saving at home” programme, accessed on 15th March 2022

- Statista, ‘Average monthly electricity wholesale prices in selected countries in the European Union (EU) from January 2020 to January 2022’, accessed on 23rd February 2022

- Vettas Nikos, Danchev Svetoslav, Maniatis Giorgos, Paratsiokas Nikos, Valaskas Kostas “The Energy Sector in Greece: Tendencies, perspectives and challenges”, Dianeosis Institute & Foundation for Economic & Industrial Research (IOBE), 2021 (in Greek)

Footnotes

- According to the latest Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT) publication on the Consumer Price Index, housing costs have increased by 22.6% between January 2021 and January 2022 due to increases in rent, electricity, natural gas and heating oil costs.

According to the market and consumer data provider Statista, the average monthly electricity wholesale price in Greece increased from 58,39 EUR/MWh to 227,35 EUR/MWh between January 2020 and January 2022 – i.e. it increased by 289%.

According to the Independent Power Transmission Operator (IPTO or ADMIE in Greek) , the weighted average electricity price in the same period increased from 67.3 EUR/MWh to 252.5 EUR/MWh, an increase of 275.2%.

According to a report published by the Australian Energy Council on 3rd February 2022, Greece has the 9th most expensive energy of the 38 OECD countries on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis.[↩] - This number is confirmed by the National Recovery and Resilience Plan “Greece 2.0” – Pillar 1: Green Transition, measure 1.2 “Energy Renovation on Residential Buildings”[↩]

- The calculation concerns single-person households[↩]