Climate + Housing = ?

The changes that are happening in our lives because of the climate crisis are devastating. Be it the changing weather, the investments taking place in all sectors of the economy, or the dominant political discourse and subsequent policies, at an international, European, and national level, everything points to the fact that we are living in a time of great transitions.

However, in addition to the urgency for a rapid and immediate reduction in greenhouse gases (GHGs) emissions, there are growing concerns about whether the necessary transitions will be just. In other words, whether they will represent a genuine opportunity to mitigate social inequalities, strengthen social cohesion, and improve the quality of life of a large section of Greek society that finds itself in a vulnerable position, especially after the economic crisis.

Eteron launches the “Mind the roof” project, as a meeting point of its two preceding projects, “Sky-high Rents” and “Climate Crisis and Elections”, aiming to investigate whether the changes that are taking place in the housing sector due to climate policies, are fair or not. In the present analysis, we shall attempt to identify the answers to several crucial questions, by reviewing the relevant Greek and international literature, aiming to highlight exactly how these changes affect each and every one of us:

How significant are the changes occurring in the housing sector due to policies and funding to mitigate the climate crisis? How much are they expected to intensify in pace and scope in the coming years? What conclusions can we draw about the energy upgrade programmes that have been implemented so far in the housing sector? What is ultimately the significance of these changes for Greek society, both in the present as well as in the future, in an era of multiple crises?

The effects of the climate crisis and the goals for its mitigation: Greece

Although the following information is widely known, any discussion regarding the climate crisis needs to start with a general assessment of the existing situation, as it is what determines the scope of the changes that need to take place over the coming decade.

So, in May 2023, in its working paper1 on the evolution of the green transition in Greece, the OECD summarised the impact of climate change in Greece:

“Greece is already experiencing relatively large human and economic losses from climate change, which are likely to increase with a warming climate. Average daily temperatures in Greece are likely to be 1-to-2 degrees higher than in pre-industrial times by 2050 if the global community manages to sharply lower emissions, and may be 2-to-3 degrees higher if emissions are high. […] As a Mediterranean country, Greece is particularly vulnerable. Extreme weather events such as forest fires, frequently involving casualties, are on the rise (Figure 23, Panel A), and the economic losses are high.

Deaths from heat waves in southern Europe will likely be ten to forty times higher by 2050 compared to the period before 2010. Precipitation may decrease by 5-10% by 2050 if emissions are low and 10-20% if emissions remain high. Water stress is relatively high and will become more severe with higher water demand and lower rainfall during hotter summers. 21% of its coastline is vulnerable to a one metre rise in sea level, which is projected to rise between 0.2 and 2 meters by 2100. This can lead to flooding and coastline erosion, while one-third of the population live within 1-to-2 km of the coastline.

An impact assessment from 2011 by the Bank of Greece, which is currently being updated, found cumulative losses of climate change corresponding to two to three times annual GDP until 2100, depending on the level of global warming; recent analysis estimates GDP in 2050 to be up 3.5% lower if emissions are contained in line with the Paris Agreement, but up to 13% lower if average temperatures rise by more than 3 degrees”.

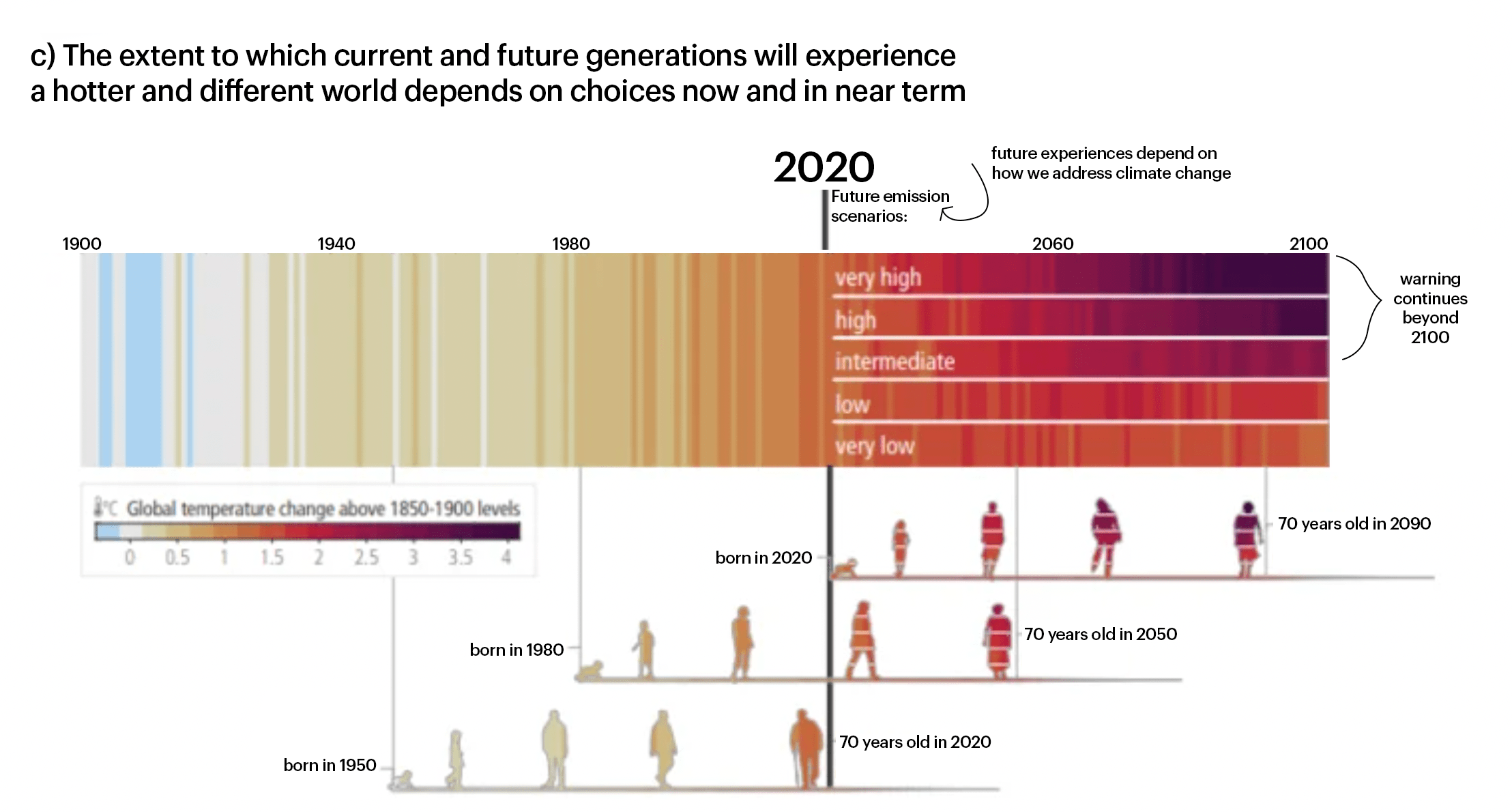

Figure 1. IPCC 2023

The key precondition for keeping the temperature increase within the limits that will lead to the smallest possible impact, is that the global community does not exhaust its remaining carbon budget by 2050. This, in early 2020, was estimated to be between 300 and 500 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent2.

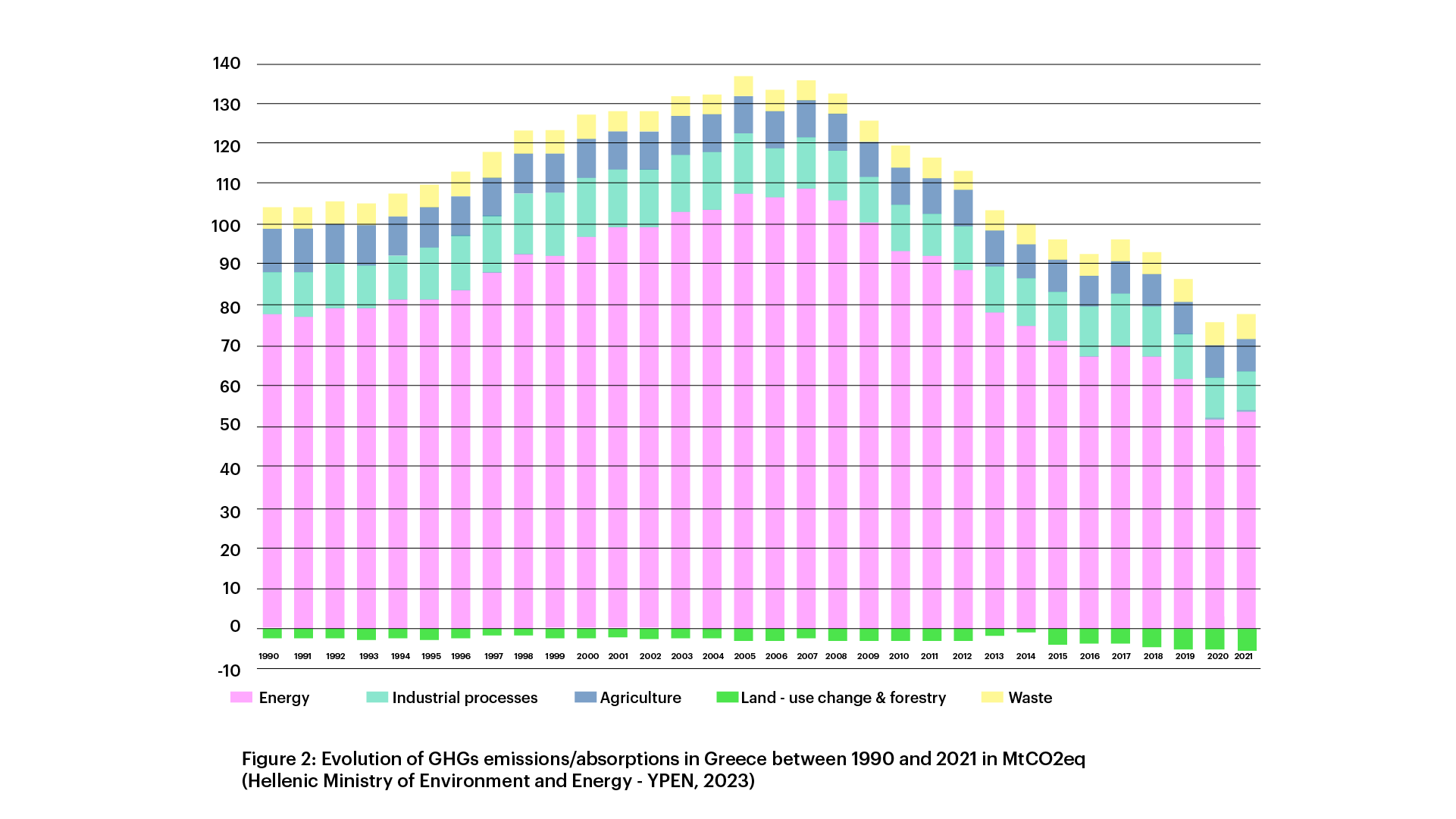

The corresponding carbon budget for Greece in 2023 is 0.45 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent3 (one gigaton equals 1 bn tonnes), while in 2020 our country emitted 74.8 million tonnes4, a significant reduction from 2008, when emissions peaked at around 140 million tonnes5 ).

However, as mentioned in a relevant report6, this decrease is partly due to the significant slowdown of the Greek economy during the economic crisis, causing a 30% drop in residential electricity consumption between 2007 and 20137 .

This raises important questions as to whether a reduction based largely on the deteriorating living conditions of Greek society can be sustainable and considered a success, given that if Greece continues implementing its existing policies, it is estimated that it will have exhausted its carbon budget by the middle of the coming decade8 .

Figure 29

As outlined in Eteron’s initial analysis10 for the “Climate Crisis and Elections” project, in order to keep the temperature increase within the limits that will have the smallest possible impact, global greenhouse gas emissions must peak before 2025 at the latest, and according to the UN, we need to cut global emissions by 7.6% every year for the coming decade (2020-2030).

For Greece in particular, the draft11 of the revised version of the National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) states that by 2030, GHGs emissions should be reduced by 54% compared to 1990 levels, in 2040 they should be down by 82% and by 2050, that percentage should be decreased by 93%. WWF Hellas and Greenpeace Greece12 propose even stricter cuts, with a 72% reduction in GHG emissions by 2030 and 100% by 2040, in line with the international scientific community, which points out that in order not to exceed the 1.5-2°C limit, GHG emissions will have to be reduced drastically over the next few years13.

Housing’s contribution on climate crisis

As the results of the 2021 census have not yet been published, we continue to rely on data from the previous decade for our assessment of the situation. According to the 2011 census14, there are 6,384,353 dwellings in Greece, corresponding to 4,631,528 residential buildings, with blocks of flats being 20% more in absolute number than detached houses15.

Given that 95% of the buildings in Greece are residential, we can conclude that a significant share of the final energy consumption from building uses -a share that corresponds to 40% of the total energy consumption- is due to domestic needs16. A report on the Energy Sector in Greece published in April 2021 by the Foundation for Economic & Industrial Research (IOBE) and Dianeosis Institute reached a similar conclusion, stating that the residential sector accounted for 32.8% of final electricity consumption in 2018, second only to the services sector, which was calculated at 34.9%. According to the European Commission’s Communication on the “Renovation Wave for Europe”, this type of consumption accounts for about 35% of GHG emissions.

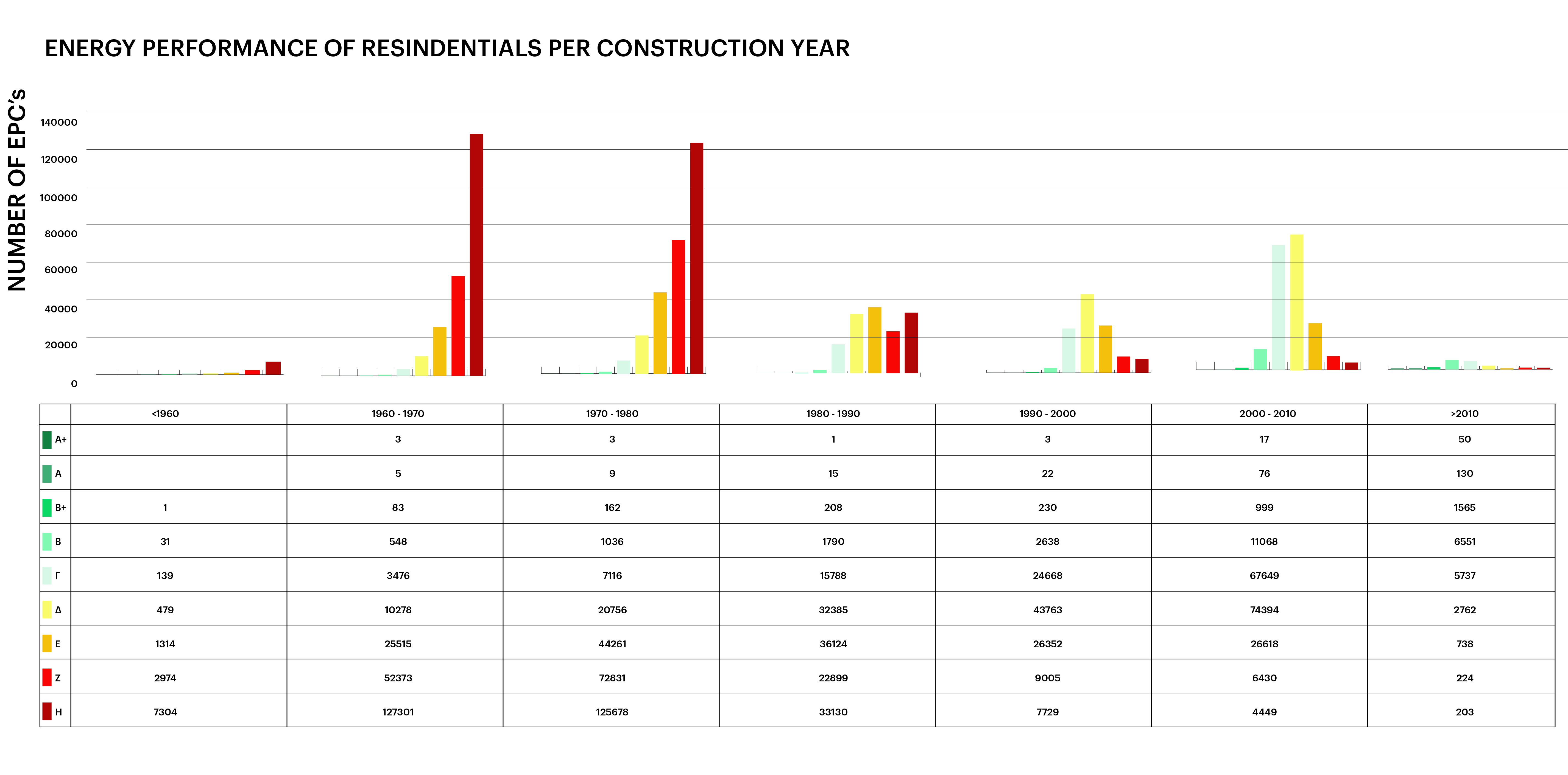

Since 85-95% of the currently existing dwellings will still exist in 205017 and 55.7% of them were built before 1980, when the Greek Regulation on Buildings’ Thermal Insulation18 was not yet implemented, the potential for reducing GHG emissions in the residential sector is enormous. As shown in Figure 3, the overwhelming share of dwellings built in that period that have an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) issued, rank in the lowest energy class (class H).

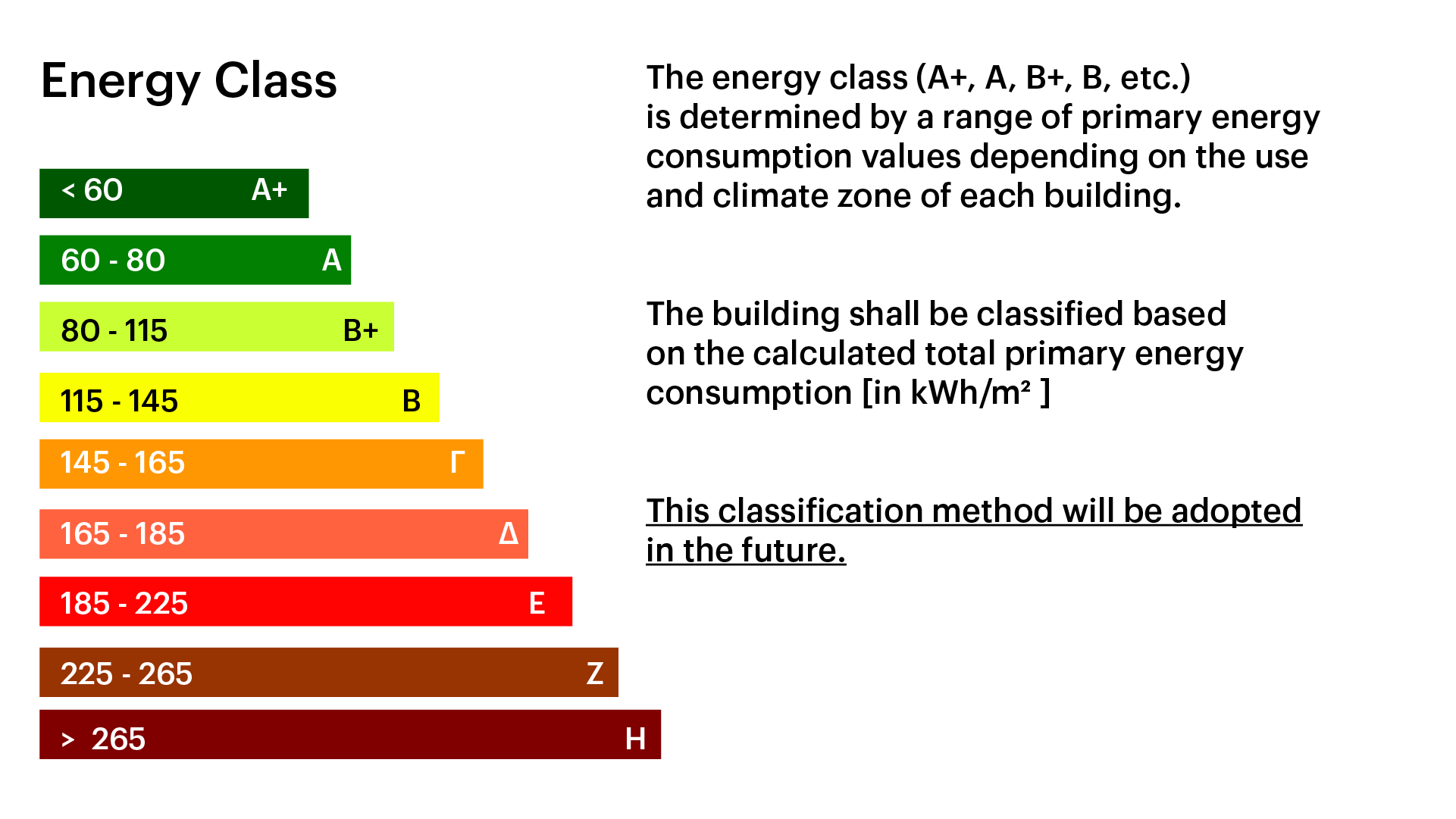

Based on the data presented in Figure 3, the percentage of dwellings built before 1980 that are placed in the two lowest energy classes, is estimated at 77%. Finally, according to the latest annual report on energy inspections19, 66% of all dwellings are placed in energy classes E-H, 30% in C-D, 4% in B/B+, and 0.2% in A/A+.

Figure 3. YPEN. 2018. Number of dwellings in Greece per construction period and energy performance based on the issued EPCs.

Figure 4. Technical Chamber of Greece (TEE – TCG). The scale used for determining the energy classes of buildings according to their total primary energy consumption in kWh/m2. For the time being, the energy class categories are based on a comparison of energy consumption with a building that’s set as a reference, with B corresponding to 75-100% and C to 100-141% of its consumption.

The same report contains some essential data on the average energy consumption in different types of dwellings. On average, apartments in blocks of flats are estimated to consume 265kWh/m2, and detached houses 428kWh/m2, with the largest share being used to cover heating needs (202kWh/m2). More specifically, in order to heat their homes, people living in apartments rely on electricity (36%), oil (46%), fossil gas (13%) and solar energy (5%) while the respective percentages for those living in detached houses are 42%, 46%, 2% and 13%.

Another aspect of the residential sector’s contribution to the climate crisis, which remains largely unresearched so far, especially in Greece, is the GHG emissions resulting from housing construction, since the above figures only concern the emissions during their use. The embodied GHG emissions in construction, as they are called in international literature, are estimated to account for about 10% of the total annual global GHG emissions20, a share that is by no means insignificant. A 2021 study21 calculated said emissions more accurately at 250-450 kg CO2 equivalent/m2 of new building.

In order to get an estimate of the scale of these emissions in Greece, we need to use the limited information available on the trendsof the construction sector in the country in the coming years. According to a special focus report by the National Bank of Greece (2023) on the country’s real estate market, we need to build 35,000 houses per year until 2030, “in order to maintain the balance between supply and demand in the sector”.

With the above numbers22, the construction of these houses will consume 1.5-3% of the country’s remaining carbon budget. A quite significant share, considering the tight margins within which we operate and the estimate that between 2030 and 2050 the construction of new buildings will increase by at least 60%23 24

Energy poverty

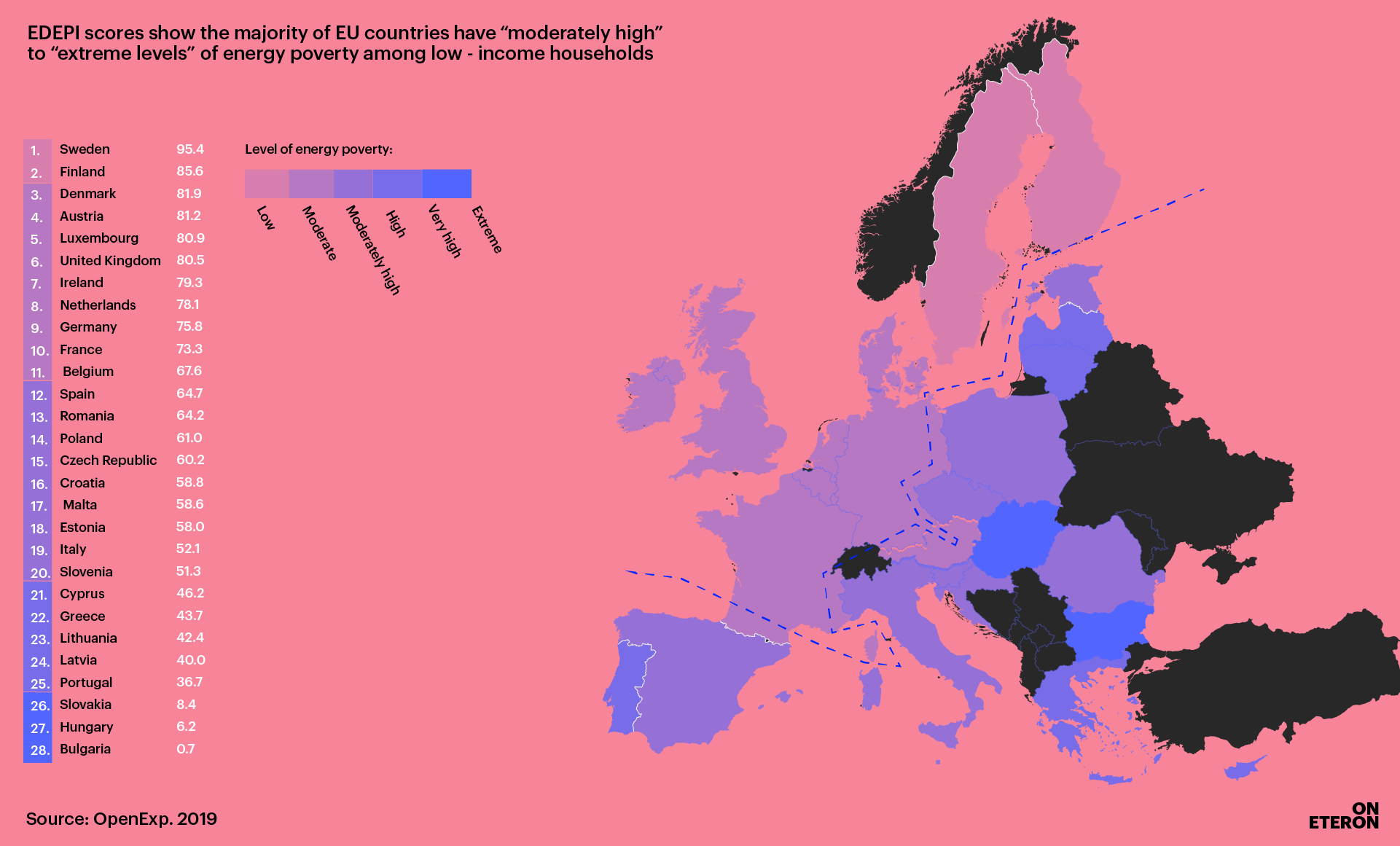

But apart from the necessity to reach our climate targets, the issue is directly linked to the quality of life of Greek society, which is one of the most exposed to energy poverty among European countries.

Figure 5. EmpowerMed 2020 – Energy poverty amongst low-income households in EU countries

In 2022, Eteron published a digital tool, called Housing360°, aiming to provide a comprehensive depiction of the scale of this particular issue in our country:

“According to data from the Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT) regarding three key energy poverty indicators, in 2020 in Greece 17.1% of households (39.1% of poor households) were unable to afford adequate heating, 28.2% (50.1% of poor households) stated that they had difficulty in making timely payments of utility bills, such as electricity, water, gas, etc. 12.5% (20.3% of poor households) live in dwellings with leaking roofs, damp walls, floors, foundations or rotten window frames. The European (EU27) corresponding averages are 8.2%, 6.3% and 14%.”

In late November, the most recent Eurostat report on housing conditions in Europe was published, more or less confirming the above assessment: in Greece, 18.7% of the total population in 2022 (10% more than in 2020) stated that they are unable to adequately heat their homes (EU average 9.3%), with that number being more than twice as high amongst the poorest households, with 38.9% of which that have an income of less than 60% of the median, stating that they face this issue (EU average 20.1%).

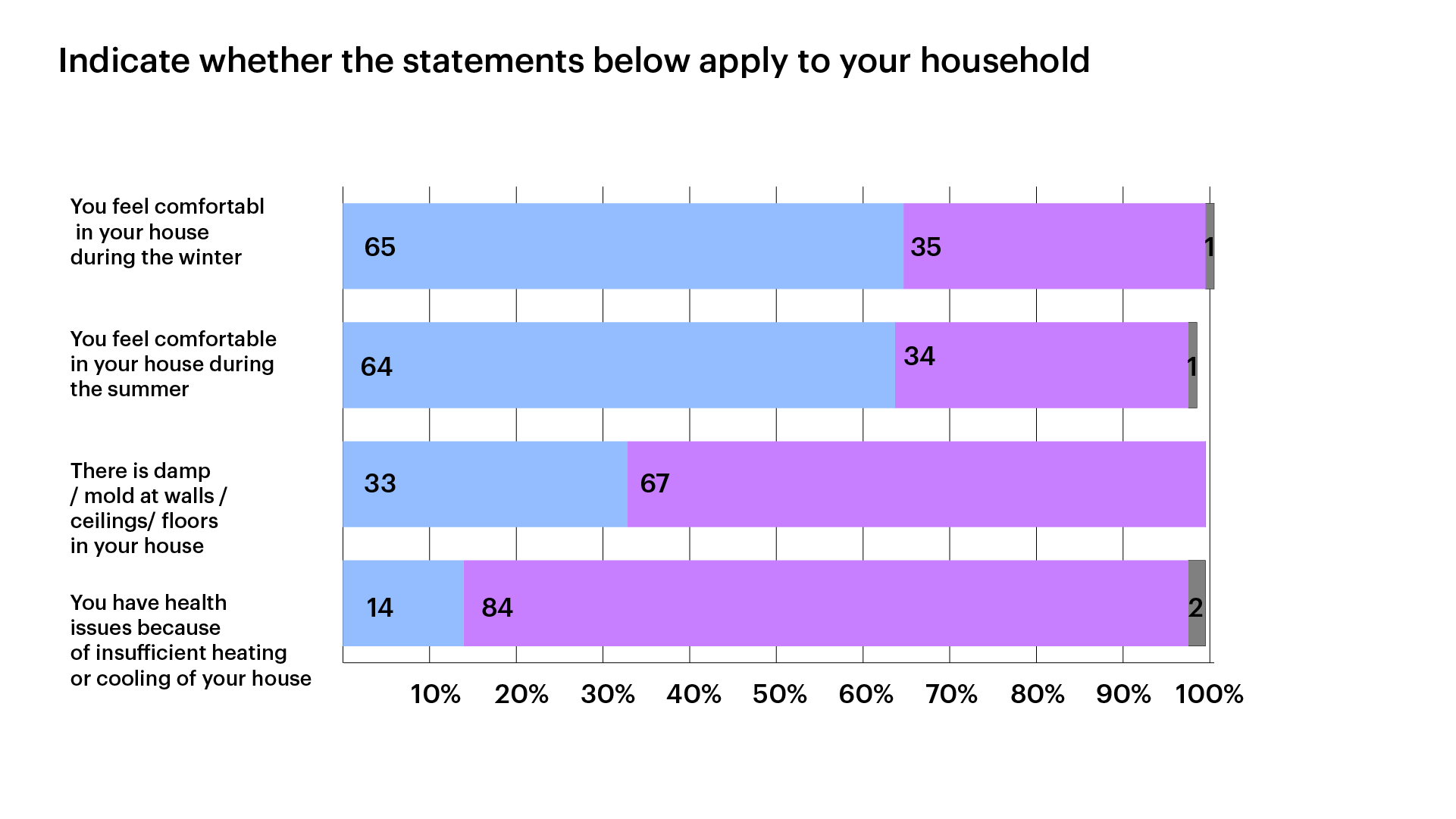

Figure 6. Nicos Poulantzas Institute 2022

The link between income and the ability to cover energy costs is further elaborated in Nikos Poulantzas Institute’s study (2022): “Households earning less than 1500€ have difficulty covering their energy needs at a rate of 58-71%, while even for those with higher incomes (1500-2500€) there is still some difficulty in that respect (32-37%), which decreases but never drops to zero even amongst households with higher incomes (over 2500€) (12%)”.

Another group of people who experience this problem with increased intensity are tenants. A 2015 study25 estimated that in rented houses, thermal energy consumption is 52% lower than that in owner-occupied homes, and 47% lower than that in houses provided free of charge. Income differences also play a major role within the rental sector, as the issues of expensive electricity, poor housing conditions and insufficient cooling/heating are significantly more prevalent amongst people paying up to €450 for their rent, compared to those who pay over €60026. An indicative case in point is the fact that it is almost six times more likely for people living in a house for which they pay less than €450 to live in poor housing conditions, while the issue of insufficient cooling/ heating is four times more likely to occur.

At this point, it is very important to point out something that Meriç Özgünes and Nikos Vrantsis emphasised when they were interviewed by Eteron, on the occasion of the publication of the Greek version of their study for FEANTSA, on the assessment of the residential energy upgrade programmes’ social impact. The issue of energy poverty is not just about the cost of a household’s energy needs, but it also concerns broader aspects of people’s quality of life, as households often cut back on other fundamental needs to make ends meet and only heat certain areas of their homes. Furthermore, they may adapt to the currently existing difficult conditions by cooking less, or by using energy forms (such as firewood, wood pellets, LPG cans or tanks etc.) that are harmful to their health and safety as well as to the environment, or even by permanently switching off appliances that use electricity27.

In conclusion, it needs to be pointed out that there is a strong possibility that the issue of energy poverty will be exacerbated in the coming years. According to estimates published by the European Central Bank in 2023, the financial support given to citizens by EU governments to counter inflationary pressures, may have helped to somewhat address the issue in 2022-2023; however, a reversal of such effects is likely to happen, and inflation is expected to exert greater pressures in 2024-2025.

What do we know about the energy upgrades that have been carried out so far?

With the above in mind, the high significance of residential energy upgrade interventions in Greece becomes very clear. If done properly, they have the potential to contribute significantly both to the reduction of GHG emissions as well as to the improvement of living conditions, the mitigation of inequalities and, as a consequence, bolstering the resilience and cohesion of Greek society. This is why we need to examine what the footprint of energy saving programmes in the housing sector has been so far.

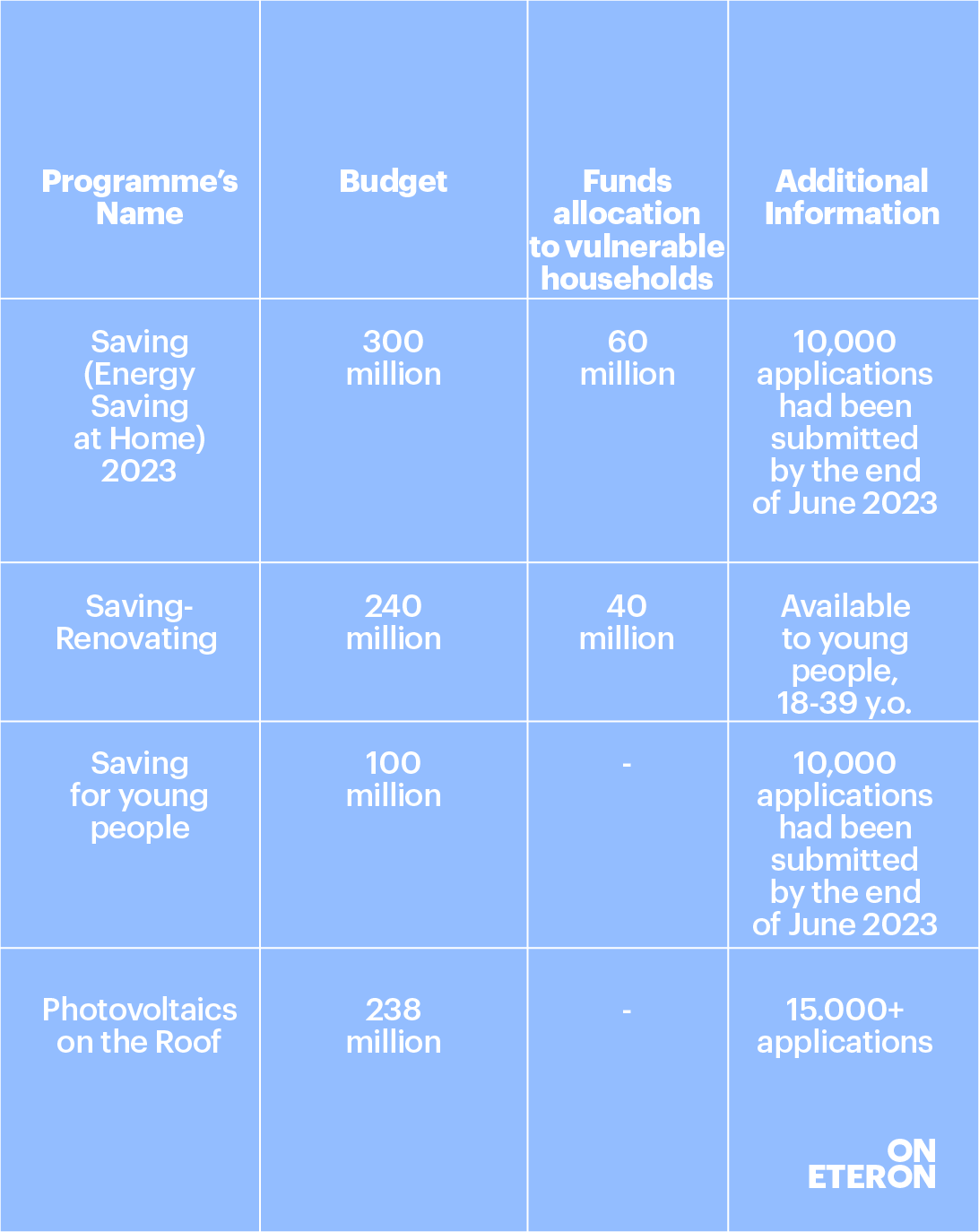

Such savings programmes have started in 2011, passing through different stages of implementation, until we reach the current main energy upgrade tool, called Energy Saving at Home 2023 (Exoikonomo – hereinafter “Saving”), which is implemented in parallel with other relevant housing programmes (Table 1).

Combining information drawn from the 2014 National Energy Efficiency Action Plan and the Institute of Energy for South-East Europe’s (IENE) study on the Greek energy sector (2023), we can get an overall idea of the scale of the programmes for the period 2011-2021. Between 2011 and 2020, the goal was to upgrade 270,000 homes, but the final number of homes that were renovated was 103,000, rising to 140,000 if we include upgrades that took place in 2021. The above figures are largely confirmed by other publications28 29, by the Ministry of Environment, estimating the number of upgrades that have taken place until the end of 2020, at 110,000-140,000. Therefore, the programmes only reached 50% of the set quantitative target during the above-mentioned time period.

Figure 7. LSE 2023

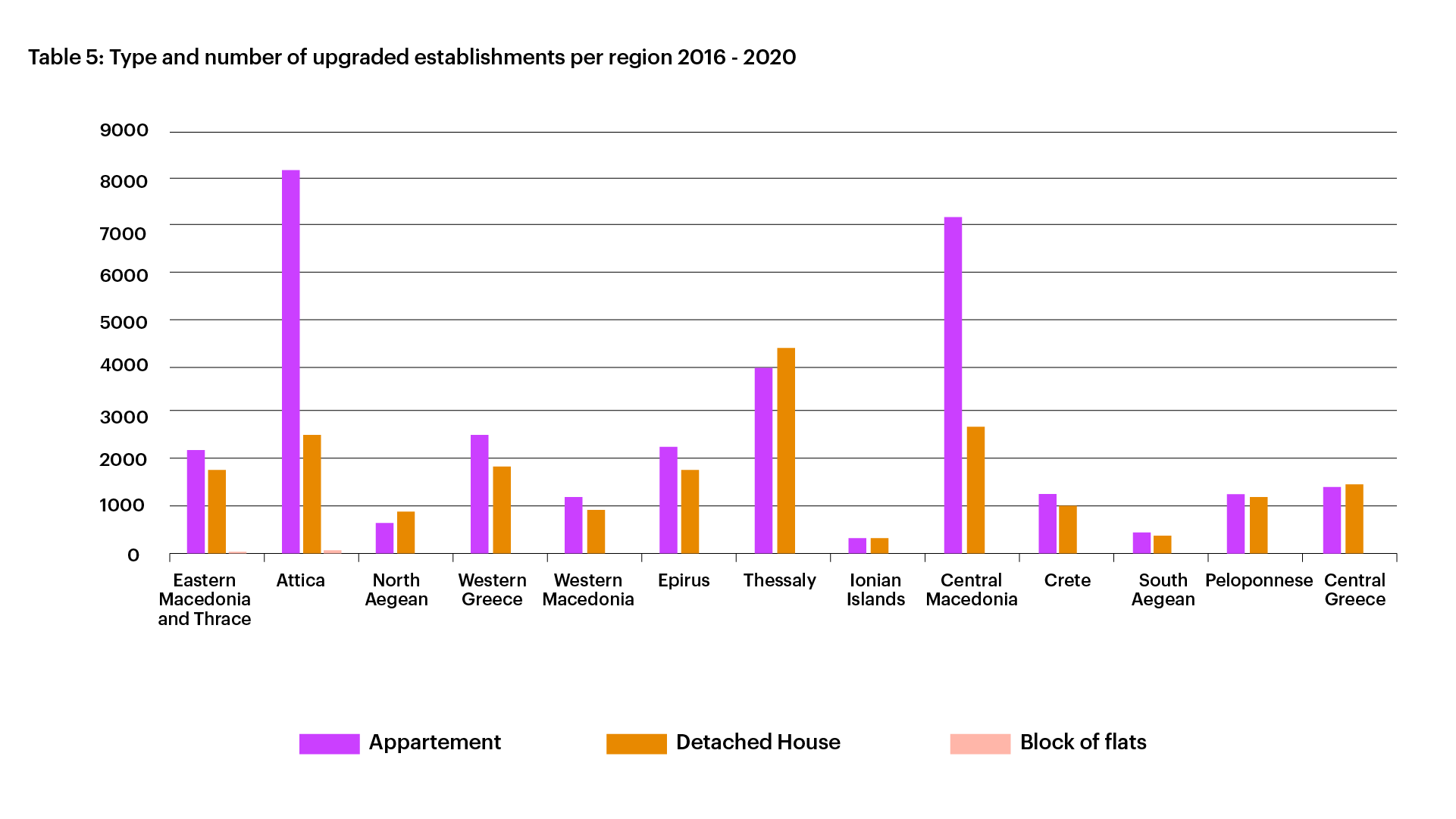

Figure 8 shows more details regarding the distribution of energy upgrades between 2016 and 2020. It quickly becomes apparent that, contrary to what happens in the rest of Greece, where there is an equal distribution of upgrades between detached houses and apartments, in the two largest urban centres (namely Athens and Thessaloniki), where most of the energy upgrades are carried out, they are more often done in apartments. It is also very important to stress that the renovation of entire blocks of flats is almost non-existent, with just a tiny number of such interventions occurring exclusively in the Attica region.

In addition to the sheer number of energy-upgraded houses, it is equally important, if not more so, to evaluate the intervention itself at a dwelling level. With the minimum threshold for being included in the Savings Programmes being set at 30% energy savings30 31, the results are to a large extent predictable. However, the available data show that interventions have an even smaller energy footprint.

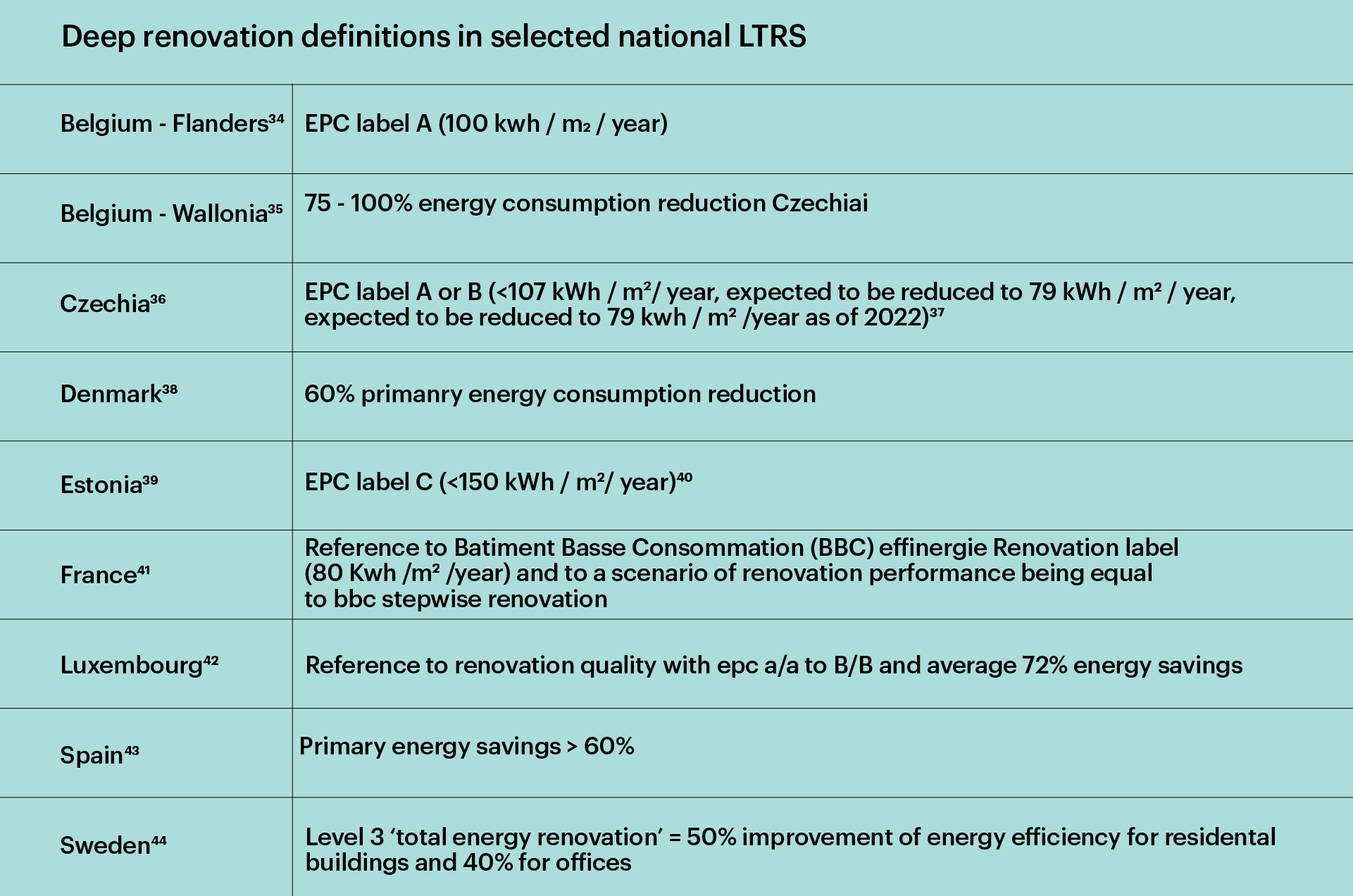

Before we continue, we need to clarify the difference between very light, light, medium and deep renovation. As shown in Figure 9 below, there is no generally accepted definition for the above. In most cases, however, the approach suggested32 by the European Commission (2019) is used, for consistency reasons: 1. very light or below threshold renovations: savings < 3%; 2. light renovations: savings between 3-30%; 3. medium renovations: savings between 30-60%; and 4. deep renovations: >60%.

Figure 8. BPIE 2021

Unfortunately, the only available comprehensive data comes from the EU study on energy upgrades for the period 2012-201620. However, read in conjunction with a study by Greenpeace Greece33 for 2015 and the long-term strategy for the renovation of the public and private building stock34, they allow for an assessment of the situation.

According to the EU study, of the total number of energy upgrades carried out in Greece between 2012 and 2016, 60% were very light/below the threshold, 27% were light, 13% were medium and 2% were deep/radical.

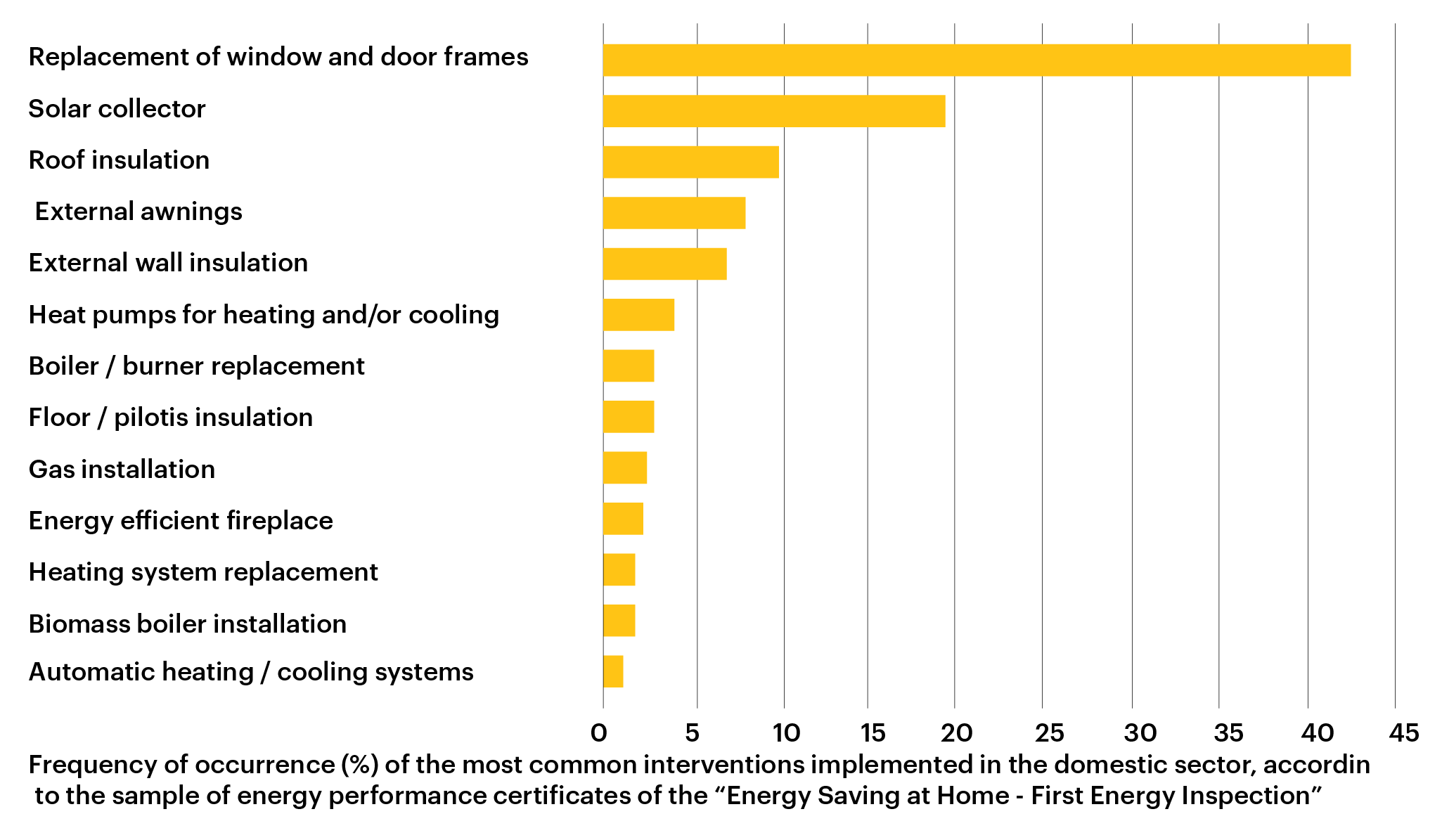

The corresponding percentages for the entire EU were: 43%, 32%, 22% and 3%. This is largely confirmed by the Ministry of Environment35, commenting that in 2015 “all the households that participated in the Saving programme almost exclusively carried out light renovations (such as changing their window frames)”.

The Ministry of Environment’s Long-Term Strategy helps us better understand the distinction by type of renovation, since it classifies window frame replacement as a light renovation, while those that include, in addition to the change of window frames, the insulation of the building shell and the roof, as moderate renovations. At the same time, Figure 10 shows in greater detail the most common type of energy upgrade interventions that were carried out in the period in question.

Figure 9. Greenpeace 2015

Of course, the most important measure of success of the above interventions, strictly within the context of energy saving, is the percentage reduction in energy consumption after completion of the interventions. And unfortunately, the EU study shows that the majority of the interventions (very light and light renovations) only resulted in energy savings of 0.1% and 13.2%, respectively. Furthermore, Greenpeace’s study provides further information, according to which: “by installing double-glazed windows, the actual energy consumption for heating was reduced by an average of 21%, by changing from an oil boiler to a gas one, the reduction is around 17%, and in the case of a change to a heat pump in detached houses, the average primary energy saving is around 37.7%”.

Against this background, reasonable doubts arise as to whether the objectives of the new Saving programme will be reached, namely whether Greece will “achieve primary energy savings of more than 30% for each beneficiary/building, through energy upgrading by at least 3 energy categories36”. According to the NECP (2019), such interventions should be carried out in 60 thousand buildings or building units each year on average, so that by 2030, 12-15% of all dwellings will have been energy upgraded37

Table 1. ΙΕΝΕ 2023 – Energy Saving Programmes for dwellings, available in 2023 (table compiled by the author)

Unfortunately, while the data from the 2021 annual technical report of the Energy Inspection Department is the most recent, it does not allow for a substantial assessment of the situation, as it is mostly based on percentages and not on absolute figures regarding the number of interventions and the energy saving achieved. However, we must present a key element: “Regarding the residential buildings that participated in the programme ‘Saving I, II, IIb, Saving 2020, Saving 2021’, we found that the majority of them (61.08%) are classified in energy categories C-E following the energy interventions, and since 2021, in the energy categories B-A+”.

Apart from the level of energy saving achieved after a house participates in the “Saving” programmes, it is important to assess the social impact of such programmes. Feantsa’s study, “Energy Efficiency Renovation: Impact and Challenges in Greece”, is the first one attempting to evaluate how these interventions affect Greece’s housing market.

Based on a sample of 450 residential properties in Thessaloniki, the authors found that homes up for sale that have been energetically upgraded, have a 35% higher sales price than those that have not been renovated38.

In contrast, after researching the rental market, on a sample of 225 houses available for rent, they found no difference in the rental price between renovated and non-renovated houses, noting however that this may be due to the high increases in the long-term rental market, while it is possible that renovations actually “may indirectly impact rents due to a shift of properties to ‘renovate to sell’”.

The scale of the changes that need to be made and that of those that are more imminent

With 4.6 million residential buildings in Greece, to reach the target of a zero GHG emission building stock by 2050, 120,000-150,000 homes per year will need to be upgraded39 40 . Moreover, for the housing sector to make a significant contribution to mitigating the effects of the climate crisis, its emissions will need to be reduced by 60% by 2030, compared to 2015 levels. Therefore, radical renovations should reach 3% of the housing stock per year as soon as possible, so that by 2030, 70% of the upgrades are deep, with the remaining 30% being at least medium in scale. “There is no room anymore for shallow/light renovations” concludes a relevant Buildings Performance Institute Europe (2021) study, from which we drew the above figures.

The proposals put forward by the European Parliament in its proposal for its Directive41 on the energy performance of buildings, all follow in this direction, suggesting that by 2030, 35 million building units need to have undergone radical renovation in order to reach the target of an annual energy renovation rate of 3% or more for the period up to 2050. The same target is reiterated in the Commission’s Communication on the Renovation Wave, which calls for an increase in radical renovation rates.

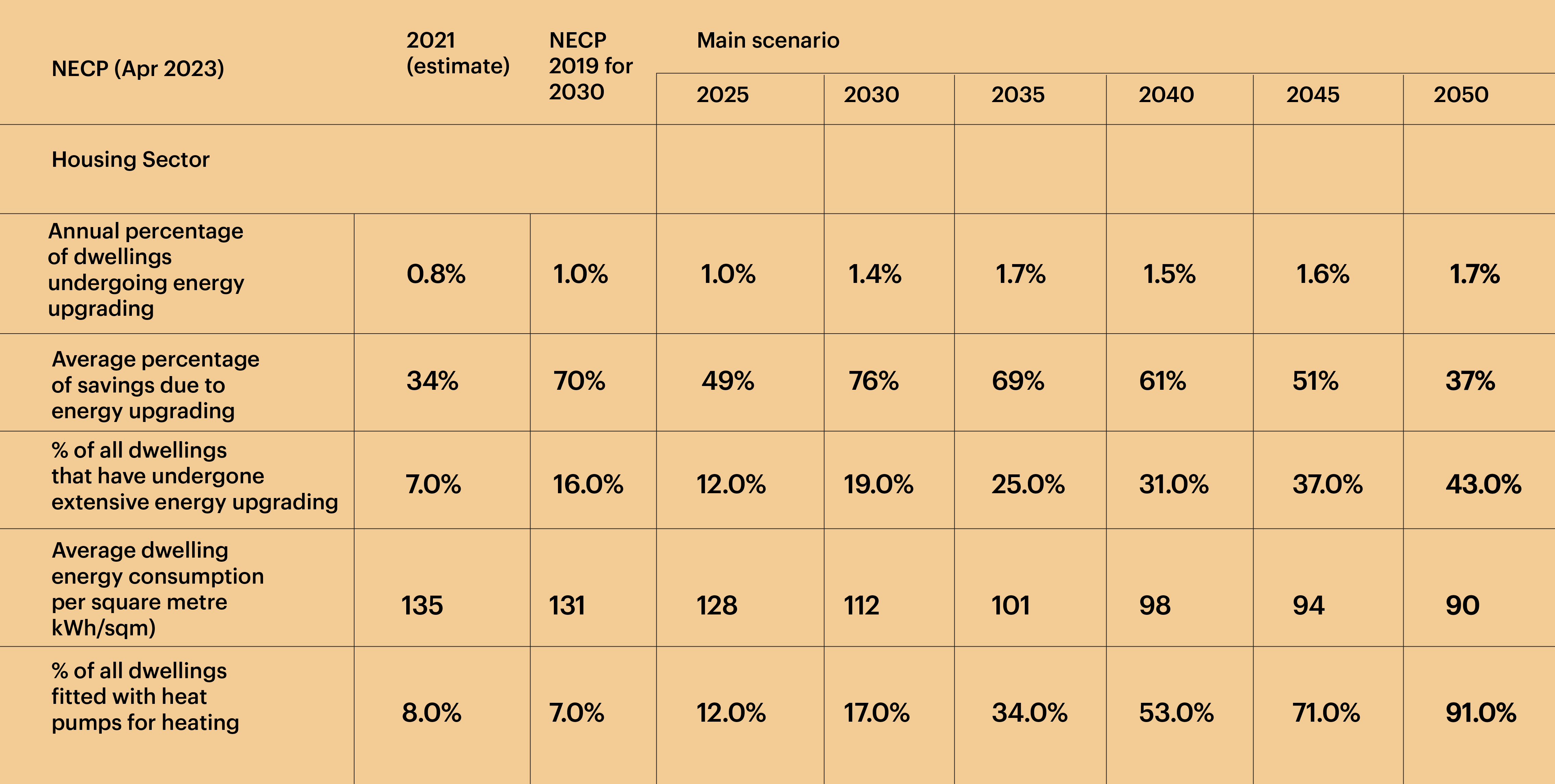

The need to increase the scale of these interventions is also expressed in the Ministry of Environment’s Long-Term Strategy42. However, the targets set in the draft of the revised NECP43 are considerably more contained than the above targets, with renovation rates per year being set at 1-1.7% of the total building stock, without specifying the type of renovation. This raises significant doubts as to how the savings targets will be met, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 10. YPEN 2023.

The matter gets even more complicated when we compare these numbers with those in Figures 3 & 4, which clearly show the current energy situation of houses in Greece. 49% of the dwellings for which an Energy Performance Certificate is issued, are placed in the two lowest energy classes (H and Z) and only 3% rank as A+, A, B and B+, which corresponds to the average energy consumption that the draft NECP estimates will be achieved even as early as 2025.

Before concluding this subsection on the scale of changes, it is necessary to list the other essential changes that are expected in the coming years and are likely to have an impact on the country’s housing stock and therefore on the conditions and costs of living of Greek society.

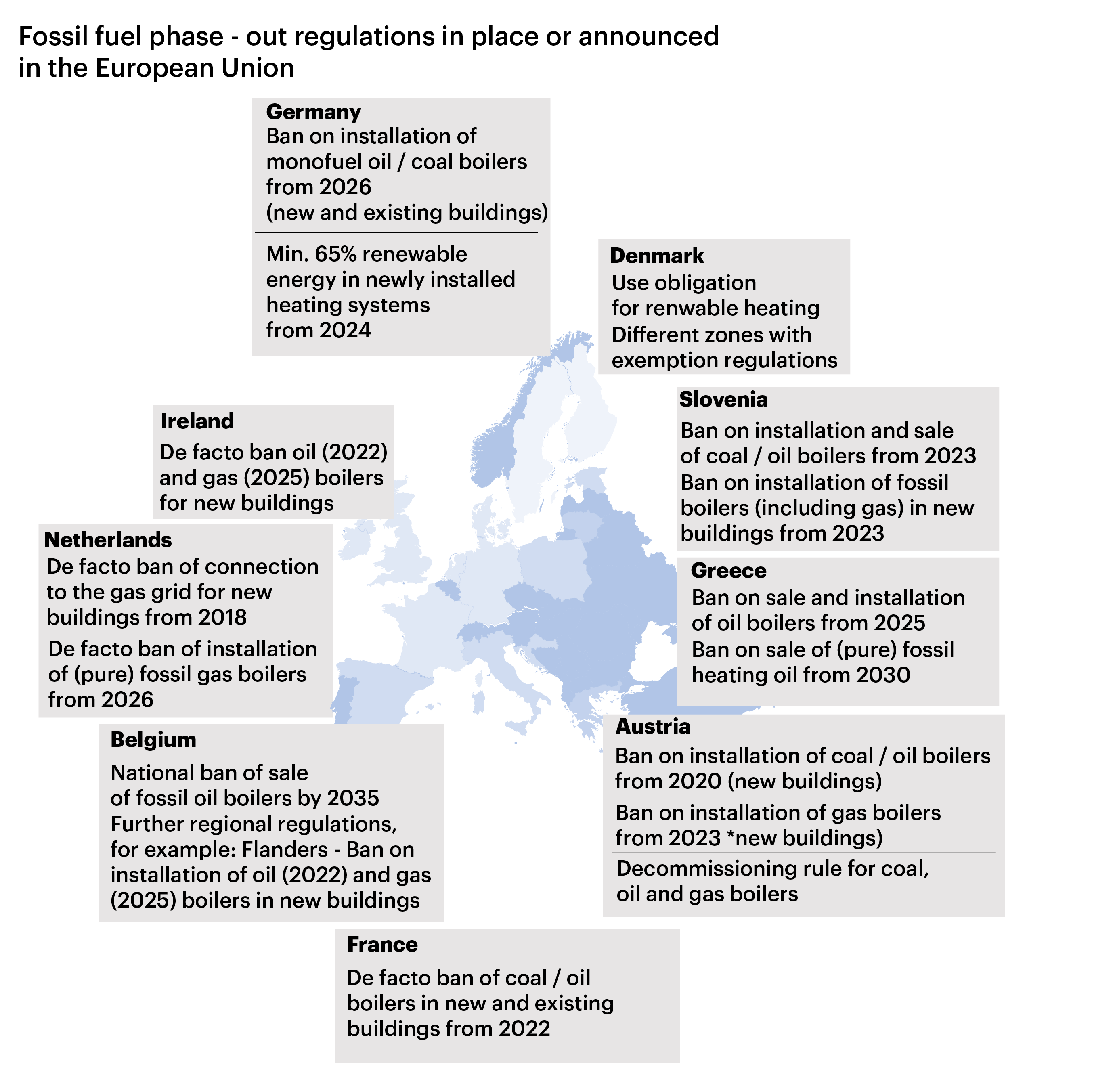

Climate Law 4936/2022 stipulated that from 2025 the sale and installation of oil burners will be prohibited and from 2030 heating oil will only be allowed to be sold for the remaining burners, blended at least 30% with renewable liquid fuels. As shown in Figure 12, such bans are increasingly being implemented in EU Member States, with several countries (such as the Netherlands, Austria, Ireland, and Slovenia) going a step further by imposing bans on fossil gas burners as well.

The strategic objective to reduce the contribution of fossil fuels to the housing stock carbon footprint is also reflected in the amendments44 proposed by the European Parliament in 2023. According to paragraph 10 of Article 15, it is proposed that starting from the 1st of January 2024, Member States do not provide financial incentives for the installation of fossil fuel-burning boilers. If this ban is actually enacted45, it will also affect the Saving 202346 programme, which currently funds the replacement of oil-burning boilers with fossil gas-burning ones.

Figure 11. Fossil fuel phase-out regulations in place or announced in the European Union (2023).47

Equally important changes will occur with the inclusion of residential fossil fuel combustion in the new emissions trading scheme, which is expected to be implemented in 202748. When it comes into effect, fossil fuel traders for home heating will have to buy emission allowances (as is currently the case for the biggest industrial polluters), while the total available allowances will decrease over time. As a consequence, households using fossil fuels for heating will be exposed to further price increases.

More specifically, based on an allowance price of €50 per CO2 tonne, the lowest income households49 will see their total fixed consumption expenditure increase by 0.21%, while the highest income households’ expenditure will increase by 0.13%. If the allowance price rises to €110, the increase will be 0.46% and 0.28% respectively50. It should be noted, that currently the price ranges between 70-80 euros, while according to estimates it is expected to increase to nearly 100 euros by 2030, 140 euros in 2040, and 500 euros in 204451 .

Acknowledging the fact that the obligation to buy allowances for residential pollutants will have a greater impact on the most vulnerable households, the EU will use part of its resulting revenues to create the Social Climate Fund. Through it, €86.7 billion will be allocated between 2026 and 2032 to support these social groups. However, the sustainability of this new system will depend on the allowances’ price, with one study estimating that an adequate reduction in GHG emissions requires a price of EUR 170, as well as on the redistribution mechanisms that will be put in place52.

The significance of housing for Greek households

Given the above information, it becomes evident that an inadequate implementation of climate policies would have a major impact on the housing stock and would cause significant changes. However, the role of housing in the finances of the average Greek family, combined with the conditions of increased housing precariousness that a large proportion of Greek society is currently experiencing, makes the stakes of the transition in the housing sector even more crucial.

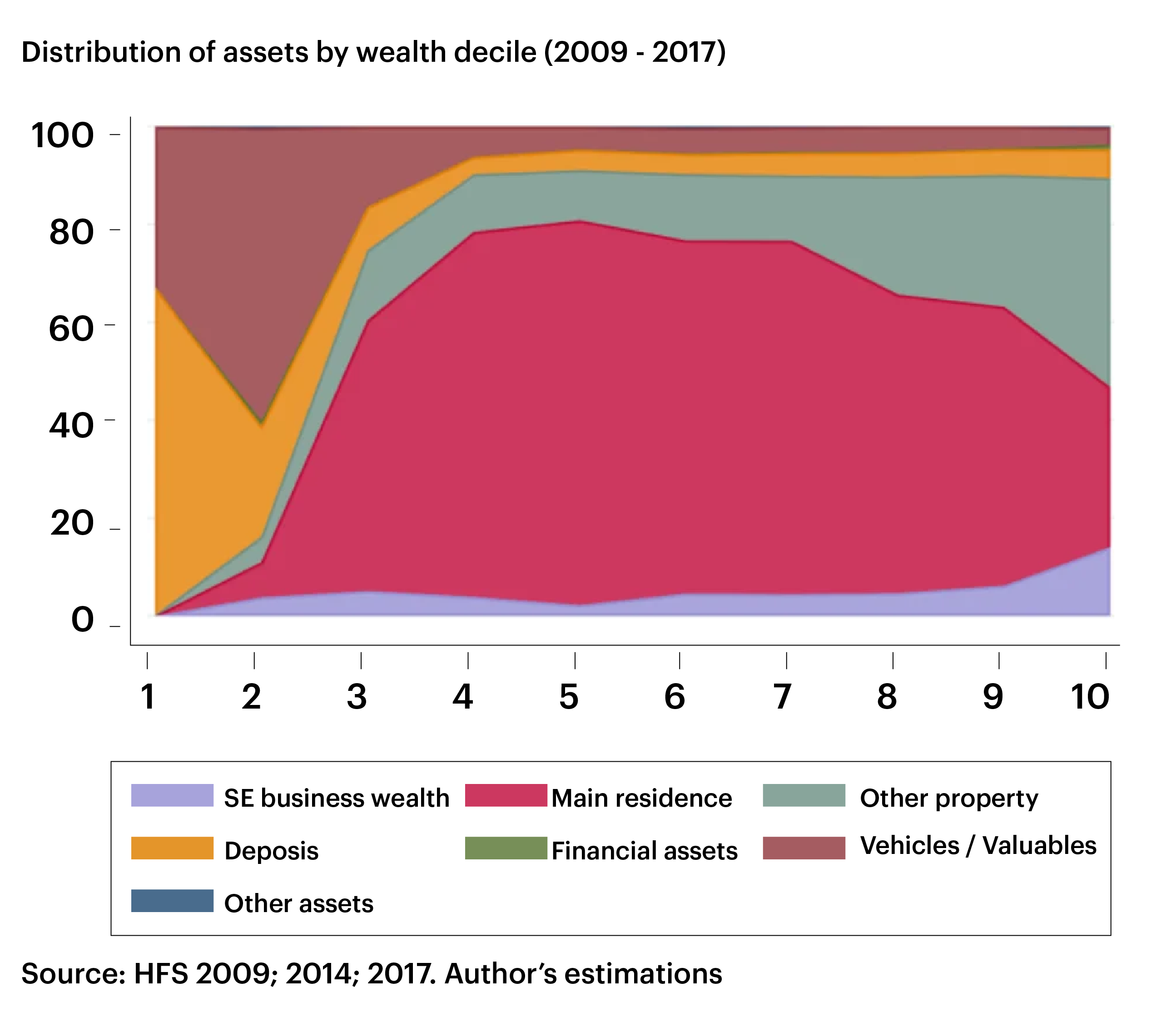

Figure 13. Distribution of assets by wealth decile. 53

The value of housing worldwide is estimated to be around USD 160 trillion, almost twice the global GDP54. In Greece, the value of housing is estimated to account for 70% of all assets in the country55, while the value of real estate constitutes 82% of the average household’s assets56. Two figures from A. Fassianos’ study on household wealth inequalities in Greece in the wake of the financial crisis help us to better understand the way in which these assets are distributed in the country57.

The significance of the primary residence for the middle and lower ranking households is clear (Figure 13), as it constitutes 80% of their total wealth, with the secondary property increasing in significance for the wealthier social groups, accounting for 40-50% of their total wealth. It is worth noting that for the poorest population groups, these percentages are practically zero, a fact that may be indicative of their increased reliance on the rental sector in order to cover their housing needs.

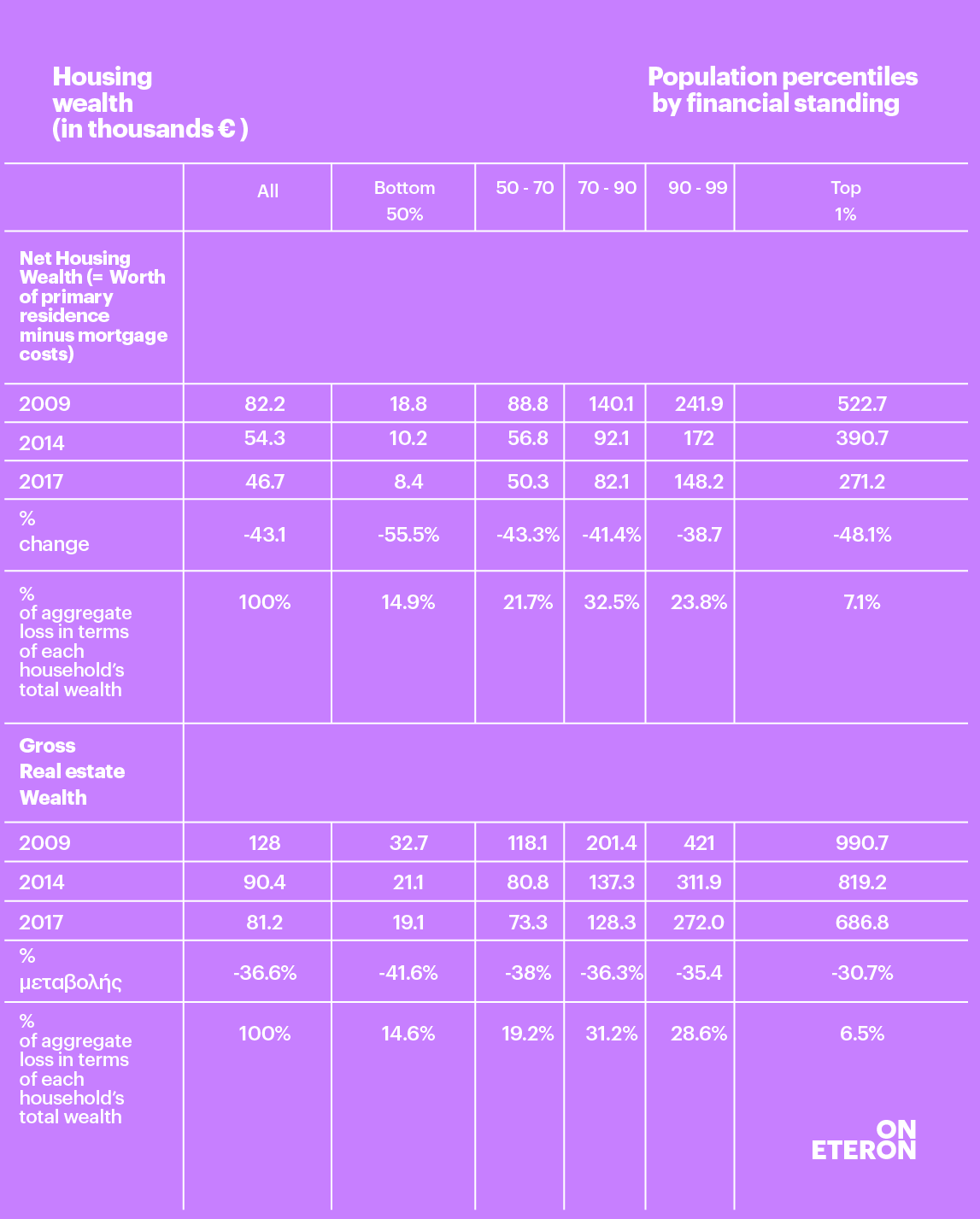

Table 2. Change in housing wealth per financial standing, 2009-2017.58

Table 2 provides additional data on the inequality in housing tenure in Greece. However, as there have been significant changes in the residential property market over the last five years, we need to be cautious in their interpretation, as they are likely to have been modified. Although all population groups experienced a huge loss of housing wealth (in the form of primary residence) due to the financial crisis, in 2017, the poorest 50% of the population had a primary residence worth just 8.4 thousand euros on average, while that of the richest 10% was worth 150-270 thousand euros. The richest 10% is also the only group that still owned additional real estate in 2017, with their secondary properties having an average worth of 124-415 thousand euros, when the other groups had secondary properties worth less than 55 thousand euros.

In the analysis “The changing housing landscape in Greece and ‘Generation Rent’”, we presented in detail the data that indicate the scale, direction, and intensity of these changes. Nevertheless, it is useful to assess whether the intensity of the pressure experienced by people renting the home they live in has changed, since that was the focus of our work at the time.

Using data from RE/MAX’s annual nationwide surveys for rental properties from 2016-2023, we can observe how rents have changed during this period. Starting by comparing the prices of 2021 with those of 2023, we can see that the high increases are still the norm, as rents in the Athens city centre have risen by 18% in two years, in the Municipality of Thessaloniki by 16%, in Volos by 33%, in Corfu by 26%, in Kavala by 11% and in Patras by 15%. For the entire period (2016-2023), the respective increases are 66%, 65%, 111%, 15%, 100%, 95%. It is worth pointing out that in the two largest urban centres the increases are much more pronounced in specific areas.

In Athens, the biggest rent increases between 2016 and 2023 are observed in the areas of N. Kosmos (121%), Exarchia (117%), Galatsi (83%), Koukaki (81%), Hilton (80%) and Aghia Varvara (80%). Similarly, in Thessaloniki, the areas with the highest increases are Meteora (95%), Pylea (85%), and Ano Poli (82%).

These figures clearly reflect the situation in the rental housing sector, considering that rental prices are in many cases as high as 9 euros per square metre, while they very rarely fall below 5 euros.

In search of resilience in a time of multiple crises

In Greece, housing is either the cornerstone of Greek household finances, a source of aggravating pressure on the disposable income of those who rent or live in conditions of energy poverty, or one of the main pillars of the Greek economy59.

In such a country, energy upgrade programmes should be seen as a great opportunity for a substantial intervention in the housing stock, which would allow to mitigate inequalities, protect large segments of the population exposed to energy poverty and housing insecurity and create a framework that will define the country’s housing strategy for the coming decades.

The difficulty of such an undertaking is certainly daunting, but so are the stakes should we fail. In fact, there are even more reasons for substantial interventions with a strong social focus, such as the volume of financial resources already allocated to housing60, the fact that medium and deep-scale energy upgrades for the time being only affect the upper and middle economic strata61, the policies that rely on subsidies to mitigate the scale of the problem but continue, in the medium and long term, to leave the most vulnerable households at risk, as well as the rising energy and housing costs, which significantly affect the rising cost of living.

However, for now, as Meriç Özgünes and Nikos Vrantis point out in their interview, given the complete lack of a regulatory framework and social criteria for assessing the outcomes, there is a significant possibility that the wave of renovations could have the complete opposite outcome, thus reinforcing the already enormous pressures experienced by a large part of Greek society.

The danger in this case is twofold. On the one hand, the living conditions of a significant segment of the population will continue to deteriorate, thereby deepening the rifts within Greek society, which in turn will become increasingly hostile to the proposed climate policies. On the other hand, those same climate policies, failing to convince society, will fail to contain the rise of global temperature, thus exacerbating conditions that have an ever greater impact on the lives, first and foremost, of the people they have left out.

- OECD. 2023. Transitioning to a Green Economy in Greece.[↩]

- European Scientific Advisory Council on Climate Change. 2023. Scientific advice for the determination of an EU-wide 2040 wide target and a greenhouse gas budget for 2030-2050.[↩]

- Greenpeace Greece & WWF Hellas. 2023. Joint comments by Greenpeace and WWF on the draft National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP). Available here (in Greek). [↩]

- Hellenic Ministry of Environment and Energy (YPEN) . Climate Law 4936/2022: The application of article 20 in businesses. Available here (in Greek). [↩]

- Hellenic Hydrocarbons and Energy Resources Management Company (HEREMA). 2023. Strategic Environmental Impact Assessment (SEIA) of the draft of the National Offshore Wind Farm Development Programme (NDP-OWF). Available here (in Greek[↩]

- ΙΕΑ. 2023. Energy Policy Review: Greece 2023. Available here.[↩]

- National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP). 2023. Preliminary Draft Revised Version. Available here.[↩]

- Greenpeace Greece & WWF Hellas. 2023. Available here (in Greek).[↩]

- Hellenic Hydrocarbons and Energy Resources Management Company (HEREMA). 2023. Strategic Environmental Impact Assessment (SEIA) of the draft of the National Offshore Wind Farm Development Programme (NDP-OWF). Available here (in Greek).[↩]

- Alkis Kafetzis. 2023. Climate crisis and elections: How many chances do we get?[↩]

- National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP). 2023. Preliminary Draft Revised Version.[↩]

- Greenpeace Greece & WWF Hellas. 2023. Available here (in Greek).[↩]

- IPCC. 2023. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland.[↩]

- Hellenic Statistical Authority. 2014. Population-housing census 2011: Characteristics and amenities of dwellings.[↩]

- Government Gazette issue. 974. 2021. Adoption of the report on the long-term strategy for the renovation of the public and private building stock and its transformation into a carbon-free and highly energy-efficient building stock by 2050. Available here (in Greek). [↩]

- ibid[↩]

- EU. 2020. A Renovation Wave for Europe – greening our buildings, creating jobs, improving lives.[↩]

- Alkis Kafetzis. 2023. Climate crisis and elections: How many chances do we get?[↩]

- Energy Inspection Departments / Northern Greece Body and Southern Greece Body. Energy inspections of buildings, heating and air conditioning systems: statistical analysis for the year 2021 and the time period 2011-2021. Available here (in Greek). [↩]

- EU. 2022.[↩]

- ASAC. 2021. Decarbonization of buildings: for climate, health and jobs.[↩]

- Taking 100sq.m. as the average size of a dwelling, based on the changes in the surface area of sold apartments over time, as reflected in the statistics and real estate price indices published by the Bank of Greece. (link in Greek) [↩]

- National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP). 2023.[↩]

- Further discussion is needed on the importance of new housing construction, taking into account OECD data (2022), according to which Greece has the highest number of dwellings per 1000 inhabitants (i.e. 600), while the average amongst OECD countries is below 500.[↩]

- Greenpeace Greece. 2015. Changing reality in the housing sector with the sun as our ally. Available here (in Greek).[↩]

- Eteron. 2022. Sky-high rents: Focusing on renters.[↩]

- Vatavali F., Katsoulakos Ν., and Chatzikonstantinou Ε. 2022. Problems, practices and perceptions regarding energy consumption in housing, part two: a qualitative survey of apartment buildings in Athens. Nikos Poulantzas Institute. Available here (in Greek).[↩]

- National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP). [↩]

- ΥPΕΝ. 2023. Implementation Guide for the “Energy Saving at Home 2021” Programme. Available here (in Greek). [↩]

- ibid.[↩]

- In the Savings II programme, the energy requirements were based on a comparison regarding energy consumption between the candidate dwelling and a reference building and were 40% energy saving for income categories 1 & 2 and 70% for categories 3 to 7. (source: YPEN – in Greek). [↩]

- EC. 2019. Comprehensive study of building energy renovation activities and the uptake of nearly zero-energy buildings in the EU.[↩]

- Greenpeace Greece. 2015. (in Greek) [↩]

- Government Gazette issue. 974 (in Greek) [↩]

- Government Gazette issue. 974 (in Greek) [↩]

- ΥPΕΝ. 2023. Available here (in Greek). [↩]

- In an article (B2Green) published on 3 December 2023, market professionals submit specific proposals for the improvements that need to be made to the “Saving” programmes, including one suggestion that the programmes should even subsidise projects that upgrade the energy class of dwellings by only one category. Such a development, if put in place, would push energy upgrades in Greece in the complete opposite direction to what the existing conditions require (see next subsection). [↩]

- Another study estimates the increase in energetically upgraded properties sales’ price at 3-20%, while the Hellenic Property Federation (POMIDA), at 2-7% (Ozgunes M. and Vrantsis N. 2022). [↩]

- OECD. 2023.[↩]

- ΙΕΑ. 2023.[↩]

- European Commission. 2023. Amendments adopted by the European Parliament on 14 March 2023 on the proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the energy performance of buildings (recast). [↩]

- Government Gazette issue. 974 (in Greek) [↩]

- NECP. 2023.[↩]

- European Commission. 2023.[↩]

- According to certain sources, the last trilateral discussions, which will determine the final content of the revision, took place on 7 December.[↩]

- EU. 2022.[↩]

- Braungardt S., Tezak B., Rosenow J. and Bürger V. 2023. Banning boilers: an analysis of existing regulations to phase out fossil fuel heating in the EU. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. Volume 183.[↩]

- ΕC. ETS 2: buildings, road transport and additional sectors. [↩]

- Another study estimates that this particular group will see their heating costs rise by 6% as a result of this regulation.[↩]

- Οeko Institute. 2022. The social climate fund – opportunities and challenges for the building sector. [↩]

- ΕRCST. 2023. State of the EU ETS Report.[↩]

- ΕPG. 2022. The impact of the proposed EU ETS 2 and the Social Climate Fund on emissions and welfare, evidence from the literature and a new simulation model. [↩]

- Fasianos A. 2022. Household Wealth Inequalities in the wake of the Greek Debt Crisis. ELIAMEP.[↩]

- Savills. 2016. World real estate accounts for 60% of all mainstream assets.[↩]

- EPG. 2022.[↩]

- Kafetzis Α. 2022. The changing housing landscape in Greece and “Generation Rent”. Εteron.[↩]

- Fasianos A. 2022.[↩]

- ibid.[↩]

- According to a study by the Foundation for Economic Research (2021), the Construction sector in 2019 employed about 150,000 workers, while the rest of the Infrastructure and Construction industry, including architectural and design services, employed another 127,000 workers. Also, for every €1 spent in the Construction sector, €1.7 is added to the country’s GDP and 51 jobs are generated in the economy.[↩]

- 39% of the €4.1 billion of the Recovery Fund will be invested in energy upgrades of residential buildings by 2027 (ΙΝΖΕΒ, 2022).[↩]

- Government Gazette issue. 974.[↩]