The war in Ukraine and the new Energy era

The Russian invasion in Ukraine is causing death, destruction, fear, desperation and poverty. After all, war is the most extreme dimension of the denial of human and cultural value. Its categorical condemnation should be the starting point of every statement and analysis. It isn’t a mere geopolitical game when it causes the loss of that many lives and the destruction of a whole country.

The barrage of developments triggered by the Ukrainian war, naturally leads us to the conclusion that we have entered a new era of international relations, world economy and political affairs. It’s still too soon to have a clear image of the exact nature of this new era. Still, it’s most likely safe to assume that even after the guns fall silent, there won’t be a return to the previous state of things. We ‘re living in a historical turning point – one that we by all means wish we didn’t have to live.

One of the fields where the landscape is changing completely, is the energy field. Russia is the EU’s main supplier of natural gas and oil. The EU leaders have already decided to proceed to “Europe’s energy independence from Russia”. Still, it’s been proven time and time again that there’s quite a distance between decision making and the implementation of said decision. Especially when it comes to the energy field, things are even more complicated due to the requirements that any major energy shift has in terms of budget, time and raw materials’ availability. The EU’s (and especially Germany’s) dependence on Russian mineral fuels is such that for the time being, natural gas is still being transported through the Gazprom pipelines, even though the West has imposed the strictest sanctions possible to Moscow.

The data

It is often being said that statistics is a plausible way to distort the truth. In this particular case, we’d say it’s rather the opposite. The data presentation accurately summarises both the degree of the EU economy’s dependence on Russian mineral fuels as well as the importance that hydrocarbon exports have for the Russian economy.

- In 2019, 61% of the EU’s energy needs were covered by imported fuels. 1

- The EU imports 90% of its natural gas needs. 2

- The EU imports 97% of its oil needs.

- The EU imports 70% of its carbon needs. 3

- In 2021, Russia was the EU’s fifth largest trading partner, representing 5.8% of its total international commerce. On the other hand, the EU was Russia’s top trading partner. 36.5% of its imports were from Russia and 37.9% of Russia’s exports headed to the EU. The EU imported 158.5 bn Euros’ worth of goods from Russia. The EU’s exports to Russia are estimated to be worth 99 bn Euros. 4

- The EU imports of Russian mineral fuels were worth 98.9 bn Euros, representing 62% of the total imports from Russia to the EU member states. 5

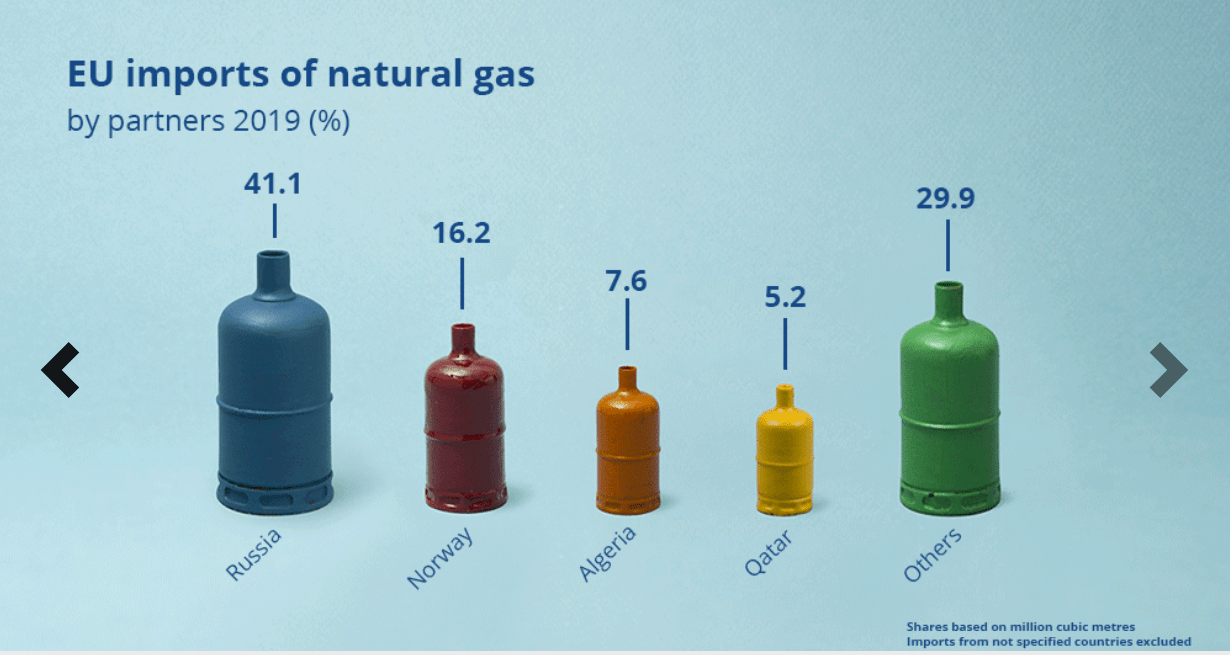

- In 2019, Russian natural gas represented 41.1% of the EU’s total gas imports. Norway’s share was 16.2%, Algeria’s was 7.6% and Qatar’s 5.2%. 6

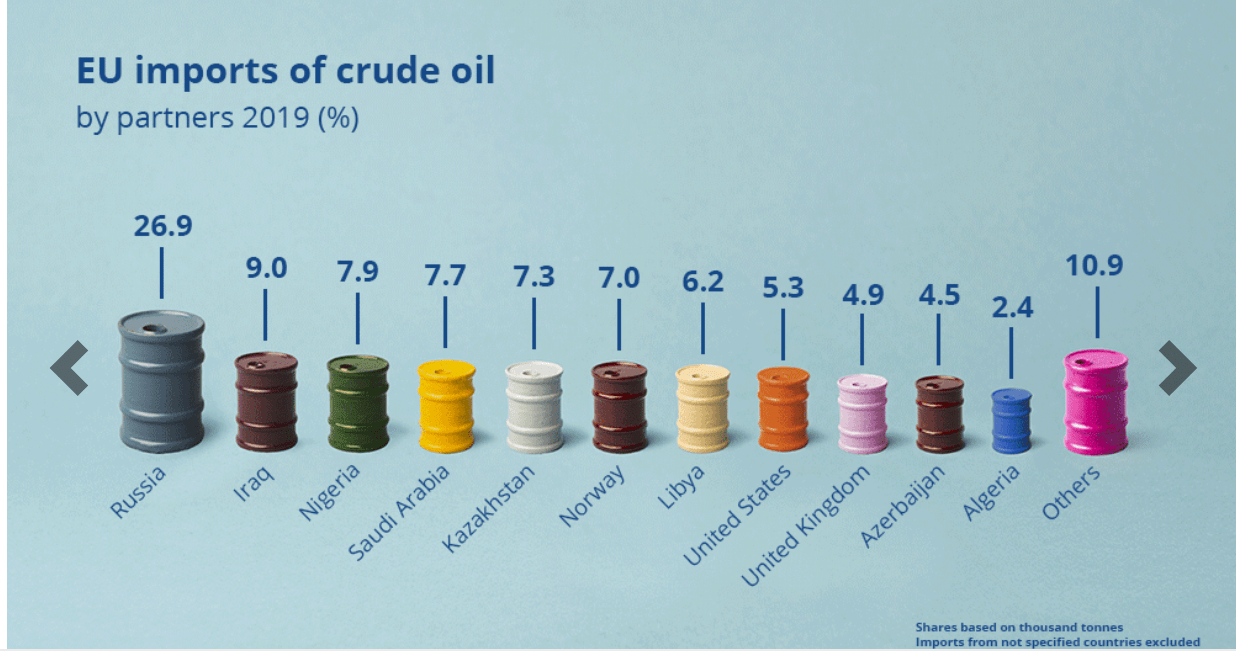

- In 2019, the EU imported 26.9% of its total needs in crude oil from Russia. 9% came from Iraq, 7.9% from Nigeria, 7.7% from Saudi Arabia, 7.3% from Kazakhstan and 7% from Norway. 7

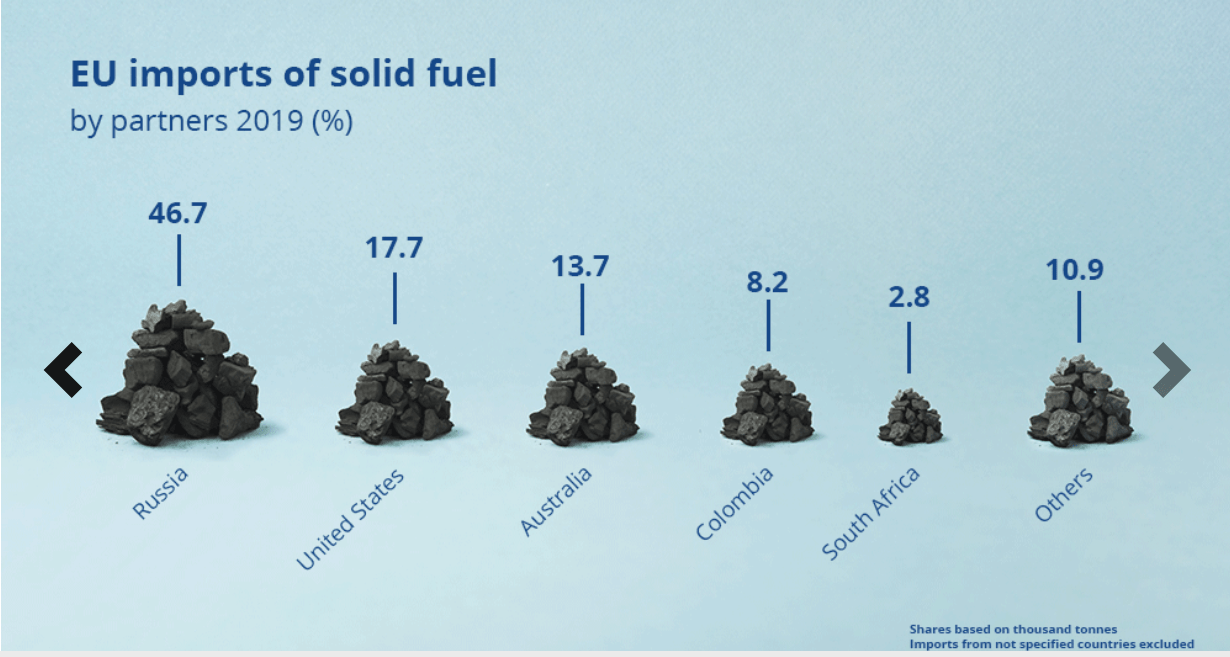

- In 2019, Russian solid fuel (mainly carbon) represented 47% of the EU’s total imports. 17.7% came from the USA and 13.7% from Australia. 8

- Russia is the third biggest crude oil producer in the world, after the USA and Saudi Arabia. 9

- Russia is the second biggest crude oil exporter in the world, after Saudi Arabia. 10

- Russia is the second biggest natural gas producer in the world, after the USA. 11

- Russia is the top natural gas exporter in the world. 12

- In 2021, oil and gas revenue made up 45% of Russia’s federal budget. 13

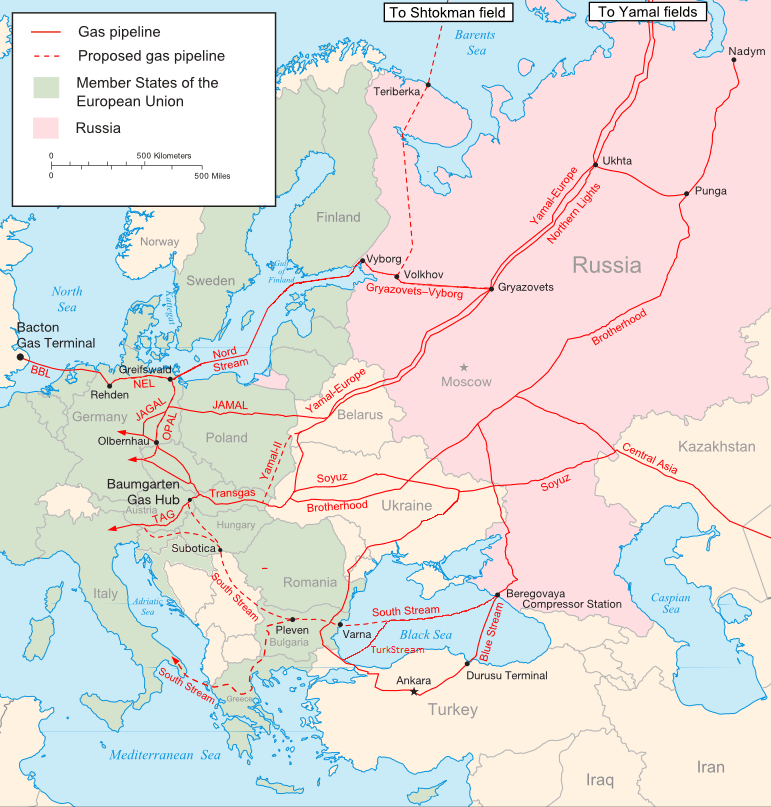

The pipelines

Map of Russian Gas Pipelines to Europe. Source: Wikimedia

Russian gas is channelled to Europe through the pipelines of a giant corporation called Gazprom, which “inherited” and expanded the Soviet Union’s pipelines to Europe. Gazprom is essentially a state-owned oligopoly producing 68% of Russian gas.

Gazprom owns the pipelines below from where it channels Russian gas into Europe:

- Urengoy-Uzhgorod. It passes through Ukraine and then Slovakia and Hungary.

- Yamal -Europe. It starts from the Yamal Peninsula in Siberia, in the Arctic Circle, and passes through Belarus and Poland to reach Eastern Germany.

- Nord Stream. It bypasses Ukraine, passes the Baltic Sea underwater and reaches Germany.

- Blue Stream. It reaches Turkey through the Black Sea.

- Turkstream. This one also reaches Turkey through the Black Sea. Part of the gas transported is then channelled to Southern Europe.

After the completion of the construction of Nord Stream, the quantity of Russian gas that has to pass through Ukraine was decreased spectacularly. In 2021, only 25% of the Russian gas that was exported to the EU passed through Ukraine, when in 2009, the percentage was 60%.

Clashing over the pipelines

On 22nd February, after Russia recognised the independence of the self-declared People’s Republics of Donetsk and Luhansk, the German Chancellor Olaf Scholz decided to halt the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, even though it is ready to start operating. Nord Stream 2 was built at the same time as Nord Stream 1 in the bottom of the Baltic Sea, bypassing Ukraine. Nord Stream 2 would double the quantity of Russian gas that would be exported directly to Germany.

The political clash over the Russian gas pipelines to Western Europe started back in the ‘80s, when the Soviet Union still existed. The Ronald Reagan administration strongly opposed the construction of the Urengoy-Uzhgorod pipeline that supplied Western Europe with Soviet gas for the first time. The pipeline was ready in 1984. In fact, the US government had imposed sanctions in order to prevent American companies from participating in the project.

The inauguration of Nord Stream 1, the largest pipeline in the world, in September 2011, was a decisive step towards what Russia and Germany called “energy security”. Bypassing Ukraine and other countries ensured the unencumbered flow of cheap Russian gas, without risking conflicts over transmission fees. Similar conflicts in 2006 and 2009 had led to the temporary halt of Russian gas flows to Europe via Ukraine. Other than the US that always opposed upgraded trade relations between Russia and the EU, ex-Soviet Eastern European countries also reacted against Nord Stream 1.

Reactions against Nord Stream 2 were even stronger, given the war that had started in Donbas and the fact that Russia had taken over Crimea. American sanctions in December 2019 were so tough, that Gazprom was forced to complete the project themselves, since the previous contractor had to bow out. At the time, Germany had expressed severe discontent with the fact that sanctions were imposed on an energy project in Europe in which the US had no involvement.

In the public discourse, after the Russian invasion in Ukraine, there have been numerous occasions where the German government has been criticised or attacked (especially across the Atlantic) for the close energy relationship they have formed with Russia. An indicative example would be Nobel-prize-winning economist Paul Krugman’s relevant articles in the New York Times.

Still, the post hoc criticism overlooks the economic benefits that the German economy has gathered from cheap Russian gas. Martin Brudermüller, CEO of the German multinational company BASF, said that cheap Russian gas has been a pillar of Germany’s very successful economic model of the past twenty years. The fact that Germany was getting cheaper energy than the rest of the market, gave her an advantage over other exporting economies. At the same time, cheap Russian energy, along with the Euro’s structure, has been a factor that increased inequality among the Eurozone countries.

The sanctions and the phase-out

After the invasion of Ukraine, the European Union imposed heavy sanctions on Russia that almost took the form of a complete economic, political, cultural and political embargo. The energy sector is exempted from the above. The significance of this exemption was also rendered clear by the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Josep Borrell’s statement that since the beginning of the war, member states have been paying Russia 1 bn Euros per day for energy provided.

Germany is the country that opposes an energy embargo more than any other. The reason is obvious: The German economy would have to pay bitter costs if there was no more Russian gas transmitted in Germany. Chancellor Olaf Scholz stated in the Bundestag that a sudden embargo would plunge the economy into recession. Additionally, the Federation of German Industries (BDI) stressed the fact that an embargo would have “incalculable consequences.”

An immediate energy embargo against Russia may not be in the books for the foreseeable future, yet in the course of the next few years, the European Union plans to phase-off Russian gas. On 8th March, the European Commission “proposed an outline of a plan to make Europe independent from Russian fossil fuels well before 2030, starting with gas, in light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.” The REPowerEU action (as it’s called) “ will seek to diversify gas supplies, speed up the roll-out of renewable gases and replace gas in heating and power generation. This can reduce EU demand for Russian gas by two thirds before the end of the year”.

Source: European Commission

[INFOGRAPHIC:

REPOWEREU TO CUT OUR DEPENDENCE ON RUSSIAN GAS

More rooftop solar panels, heat pumps and energy savings to reduce our dependence on fossil fuels, making our homes and buildings more energy efficient. Speeding up renewables permitting to minimise the time for roll-out of renewable projects and grid infrastructure improvements. Diversifying gas supplies and working with international partners to move away from Russian gas, and investing in the necessary infrastructure. Decarbonising Industry by accelerating the switch to electrification and renewable hydrogen and enhancing our low-carbon manufacturing capabilities. Doubling the EU ambition for biomethane to produce 35 bcm per year by 2030, in particular from agricultural waste and residues. A Hydrogen Accelerator to develop infrastructure, storage facilities and ports, and replace demand for Russian gas with additional 10 mt of imported renewable hydrogen from diverse sources and additional 5 mt of domestic renewable hydrogen.]

LNG

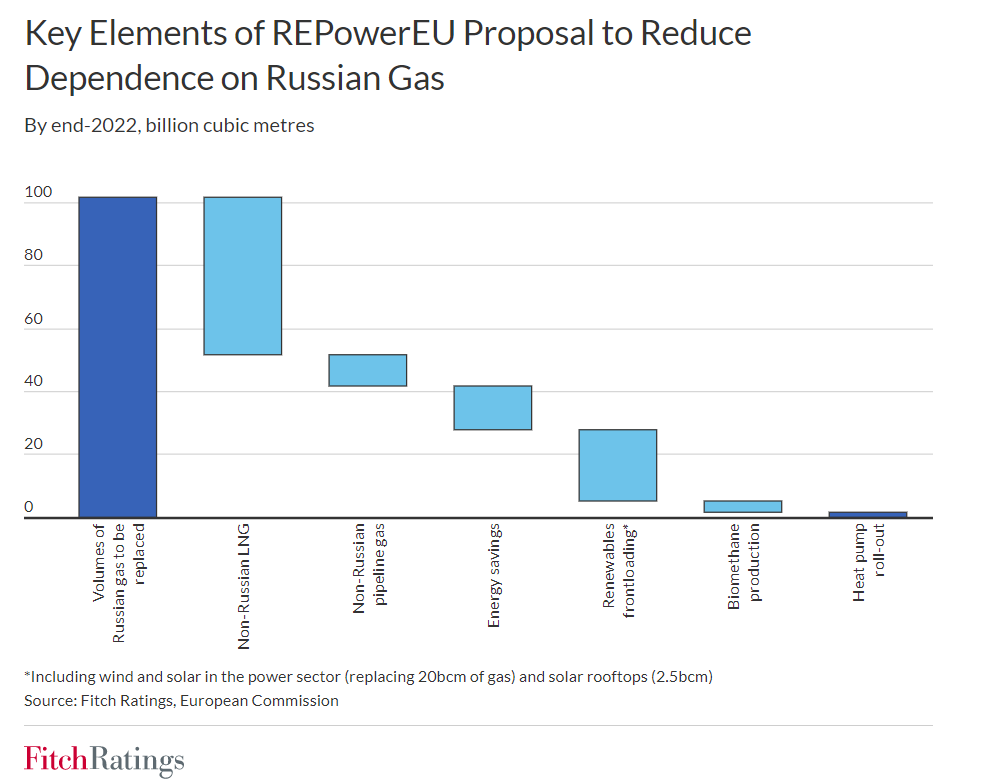

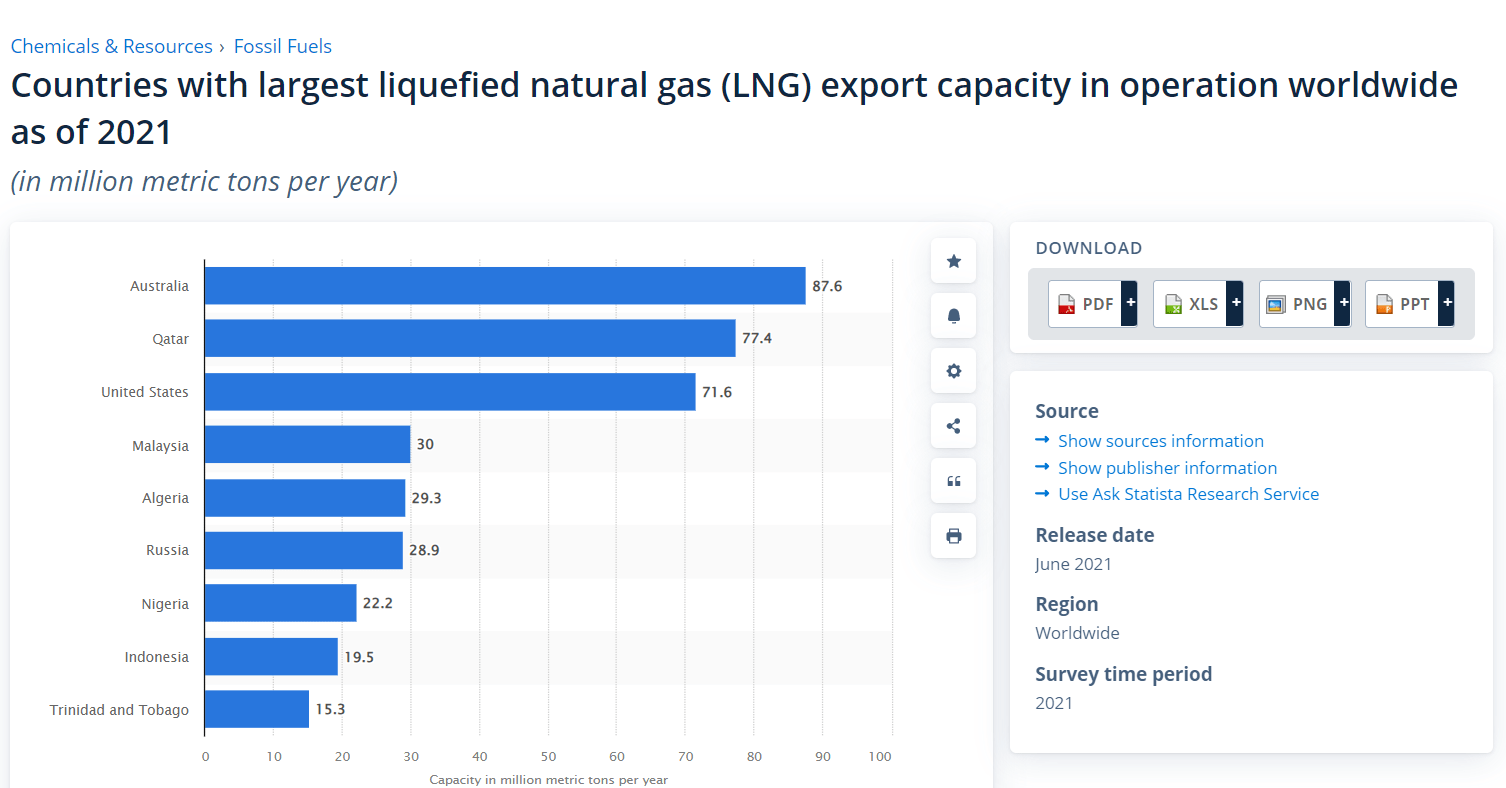

One of REPowerEU’s projection’s focal points is the replacement of 50 billion cubic metres (bcm) of Russian gas with LNG (liquefied natural gas) from other countries by the end of the year.

FITCH WIRE Russian Gas Replacement Only Feasible in Medium Term in Europe

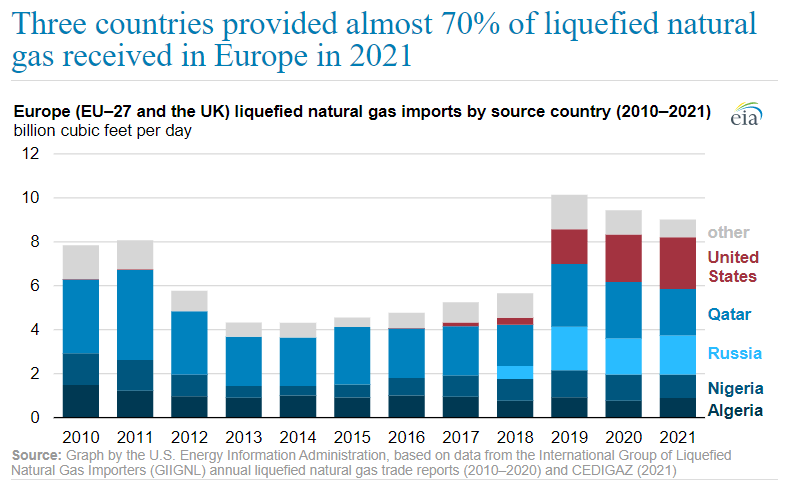

LNG made up 26% of the total gas imports from the EU and the United Kingdom in 2020. Despite the market’s vicissitudes, LNG imports seem to be increasing. In 2021, imports from the USA, Qatar and Russia made up 70% of the total LNG imports in the EU and the United Kingdom. More specifically, imports from the USA reached 26%, Qatar reached 24% and Russia 20%. In January 2022, the US supplied more than 50% of the European LNG imports.

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

In a report, Fitch Ratings claims that Russian gas replacement is only feasible in medium term. More specifically they estimate that:

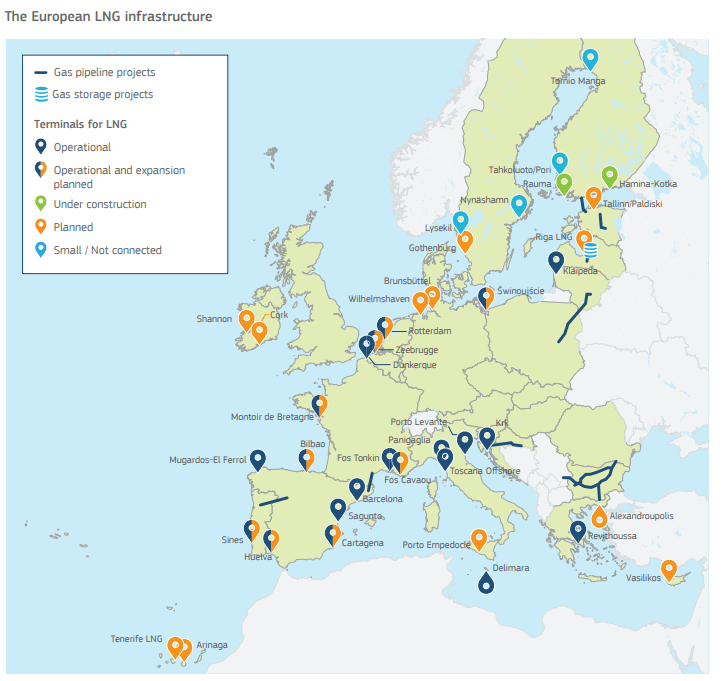

“The EU has sizable LNG import capacity of about 157bcm a year, according to the European Commission, of which only 80bcm was used in 2021, leaving room for additional volumes. However, most LNG import terminals are concentrated in Spain, Portugal, France and Italy with limited existing pipeline infrastructure to deliver gas to Germany and some Central and Eastern European countries that are most dependent on Russian pipeline gas.”

Source: European Commission EU – U.S. LNG Trade.

Fitch Ratings also underlines the fact that “around two-thirds of global LNG supplies are already contracted, leaving limited room to increase supplies to Europe, unless it offers higher prices. Recently higher LNG netbacks in Europe compared to China made shipments to Europe more competitive. We expect the LNG market to remain tight in the next two years, with Europe competing with Asia for LNG flows, keeping prices high, and more production capacity coming onstream only in the medium term.”

American LNG

American LNG could become the main fuel to replace Russian gas – a fact that explains to an extent America’s strong opposition to Russian pipelines. The USA is already the number one LNG exporter to Europe. In a joint statement on 25th March, President Joe Biden and the Chairman of the European Commission committed to the supply of an additional volume of at least 15 bcm of American LNG in the EU by the end of the year. The goal is for the additional American LNG volume that will be exported to the EU to reach 50 bcm by 2030. Still, global energy market key actors claim that President Biden’s commitment might not be able to be fulfilled, due to the incapacity of the private corporations to supply the required gas volume to the EU. Also, 75% of the American LNG is contractually bound to be sent to Asian and non-European countries.

In any case, the American government’s solution of choice in terms of the Russian gas replacement is LNG rather than new pipelines (such as EastMed). The Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs of the US, Victoria Nuland was clear in an interview she gave at Kathimerini:

“We don’t need to wait for 10 years and spend billions of dollars on this stuff. We need to move the gas now. And we need to use gas today as a transition to a greener future. Ten years from now we don’t want a pipeline. Ten years from now we want to be green. But right now we need the gas. So we’ve got to use LNG and we’ve got to use electricity connections that we can do more quickly.”

The US couldn’t have become a major global LNG player hadn’t it been for the US shale revolution. Thanks to the extremely harmful for the environment method of fracking and the use of horizontal drilling, the US managed to exploit huge oil and gas reserves that were unattainable before. In just one decade, the USA became the number one oil producer in the world and one of the top three LNG exporters. In fact, they’re expected to reach the top in LNG exports globally within the year. It is quite indicative that from 2010 till 2020, the US production increased from 7,559,000 barrels per day to 16,476,000. Respectively, natural gas production increased from 575.2 bcm to 914.6.

Source: Statista.

It is clear that the shale revolution didn’t just change the US’s geopolitical relation with Europe, but also with the Middle East, by reinforcing Washington’s position significantly.

China

On one side of the EU’s energy swap lies the question of whether or not the EU can replace Russian gas with LNG from elsewhere. On the other hand, there’s whether Russian hydrocarbons could be channelled to China instead.

We shall refer to the 2021 statistical data once more, in order to summarise the energy relationship between China and Russia:

- Russia was the second largest oil supplier in China, after Saudi Arabia. In total, it supplied China with 1.6 million barrels of oil per day, which made up 16% of the total Chinese imports.

- Russia was the third largest gas supplier in China, after Australia and Turkmenistan. It channelled 16.6 bcm of gas through pipelines and LNG, which made up 10% of the total Chinese imports.

- Russia was the second largest coal supplier in China, after Indonesia. It supplied China with 50 million tonnes of coal, which made up 15% of the total Chinese imports.

Despite the Chinese market’s significance, the EU is a more important client for Russia. In 2020, Gazprom exported 174.9 bcm of gas in Europe as opposed to 4.1 bcm in China. Gazprom’s eight pipelines that end up in Europe have 6 times the gas transporting capacity of Power of Siberia that ends up in China and started operating in 2019. Still, Power of Siberia, which delivered 10 bcm of gas last year, only operated at 30% of its capacity. At the same time, the Russian government has drafted a plan in order to increase LNG exports from 40 bcm that it delivers today, to 110-190 in 2025.

When it comes to oil, again the EU is a more significant market for Russia than China. Russia exports 2.4 million barrels per day in Europe and just 1.6 million barrels in China.

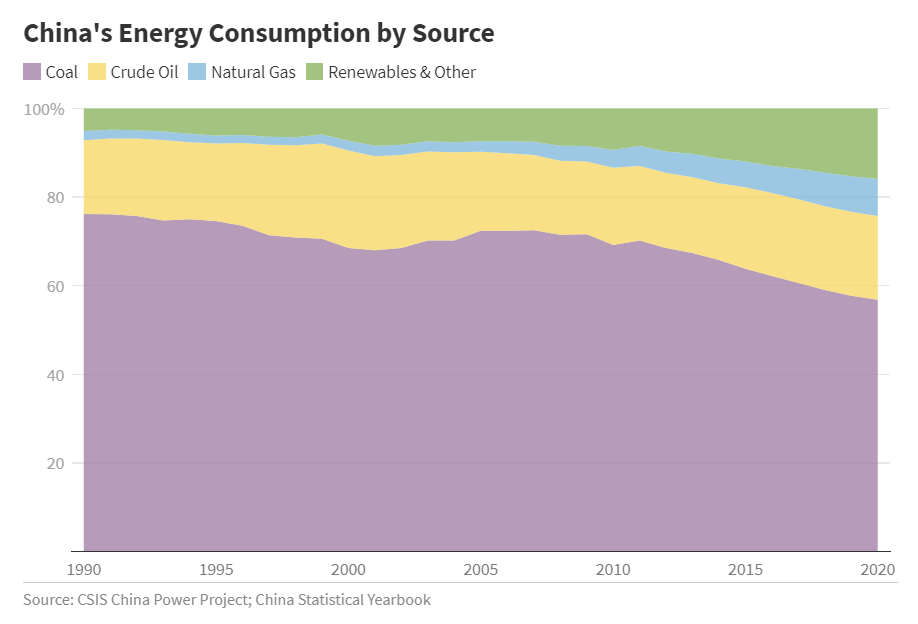

Still, the potential of the Chinese gas market is great both thanks to the country’s rapid economic growth, as well as to its need for a shift in its energy mix. Today, coal, which is an extremely polluting option, covers 58.6% of China’s energy needs. The Chinese government wants to replace it with renewable energy sources and natural gas.

Today, gas consumption in Europe reaches 541 bcm per year, while China consumes 331 bcm. Still, it is estimated that China will reach 525 bcm by 2030 and 620 bcm by 2040. Russia wants to cover this ever expanding gas market, by building a new pipeline, Power of Siberia 2 that will be able to transport 50 bcm of natural gas to China from the Western Siberia reserves that are currently supplying Europe. For the time being, though, there isn’t a final agreement on that project.

In order to channel Russian gas into China, there need to be serious investments in new pipelines, something that requires money and time. It is worth noting, though, that the giant LNG plant in the Yamal peninsula in Siberia (where under polar conditions of -40°C, they built the port of Sabetta in order to transport LNG with nuclear-powered icebreaker tanker ships) was mainly funded by Chinese credit. The Chinese participated in the project after the Western banks had to stand down because of the sanctions imposed due to the Crimea appropriation. It was the first time that Chinese interests were among the shareholders in the Russian energy industry.

Environmental concerns

The state-of-emergency situation that is caused by the war, combined with the spike in energy rates, all cause fears regarding possible delays in the phasing off mineral fuels, which is the pillar of the green transition. Regarding REPowerEU, the Executive Vice-President for the European Green Deal, Frans Timmermans, stated: “Let’s dash into renewable energy at lightning speed. Renewables are a cheap, clean, and potentially endless source of energy and instead of funding the fossil fuel industry elsewhere, they create jobs here. Putin’s war in Ukraine demonstrates the urgency of accelerating our clean energy transition.”

Yet, the creation of new infrastructure for imported LNG doesn’t conform with the direction of a rapid switch to renewable energy. Environmental organisations harshly criticise the promotion of gas as a “green” fuel. Greenpeace stated, among other things: “Let’s take a look at mineral gas’s life cycle: Not only does it emit gases when it’s burned, but also during its drilling, mining, transportation through pipelines and consumption. During those stages, the result is methane leakages, as methane is mineral gas’s main ingredient. Methane is a greenhouse gas and it’s far from harmless. The planet’s overheating potential due to methane, when calculated on a 20 year basis, is 86 times higher than that due to CO2.”

In Greece, the government decided to proceed to a series of measures that it links to the war in Ukraine. Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis announced on 6th April that lignite mining will increase by 50% in the next two years. The PM stated that: “The war led the natural gas prices to increase tenfold, thus rendering the energy production from lignite temporarily cheaper. Lignite is a last resort that will temporarily replace the circumstantially costlier and no longer abundant natural gas. The ambitious goals we had to reduce CO2 emissions by 55% by 2030 and to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 are not being disputed”.

At the same time, the Greek government decided to conduct new natural gas exploration expeditions in 6 areas (in Epirus, the Ionian Sea, the Gulf of Kyparissia and in the sea west and southwest of Crete). On 12th April, in a meeting with the Hellenic Hydrocarbon Resources Management company, the Prime Minister stated: “I would like to stress the fact that up until Russia invaded Ukraine, the commercial exploitation of new natural gas reserves wasn’t such an attractive prospect financially for countries, such as Greece, that were just entering in the game, due to the natural gas’s very low rates. This reality has changed though, and our strategy had to be redrafted due to the price trajectory of natural gas on an international scale, as well as the plans to replace Russian gas and the importance of natural gas in the coming years, given the fact that it’ll be the transition fuel (while heading to carbon neutrality).” Kyriakos Mitsotakis also said that: “My mandate to expedite natural gas explorations won’t hinder in the slightest the government’s commitment to lead the green transition. Our purpose is very simple: If there are enough available exploitable natural gas quantities, we shall replace the imported natural gas with national reserves.”

A new world

The war in Ukraine lifts the curtain of a new era in the energy sector as well. It is safe to assume that in the medium-term, the EU will significantly decrease (or stop altogether) energy imports from Russia. It is also highly likely that Russia will channel its hydrocarbon resources into China. Additionally, there should be no doubt that the new landscape that is being shaped entails increased energy costs for both producing entities as well as citizens. Things are looking rather uncertain in terms of the green transition. When it comes to political declarations, the intent is to confirm the commitments to phase-off fossil fuels. Certain actions in the field though, don’t align with said declarations.

- Eurostat, From where do we import energy?[↩]

- European Commission, REPowerEU: Joint European action for more affordable, secure and sustainable energy[↩]

- European Commission, Questions and Answers on REPowerEU: Joint European action for more affordable, secure and sustainable energy[↩]

- European Commission, Russia[↩]

- European Commission, Countries and Regions – Russia[↩]

- Eurostat, From where do we import energy?[↩]

- Eurostat, From where do we import energy?[↩]

- Eurostat, From where do we import energy?[↩]

- IEA Energy Sheet: Why does Russian oil and gas matter?[↩]

- IEA Energy Sheet: Why does Russian oil and gas matter?[↩]

- IEA Energy Sheet: Why does Russian oil and gas matter?[↩]

- IEA Energy Sheet: Why does Russian oil and gas matter?[↩]

- IEA Energy Sheet: Why does Russian oil and gas matter?[↩]