Femicide: The time has come for bolder feminist policies

The impact of feminism on public policy is a widely accepted fact. Ever since the time when women fought for their right to vote, something that became a reality for a significant part of the Western world during the Interwar years, to more recent and sometimes less iconic reforms, feminist movements have developed the capacity to shape agendas and influence the field of public policy formulation and implementation (Ackelsberg, 1992). In support of this observation, one merely needs to look at the participants’ response to the question “Do you know/ have you heard of the term ‘feminism’” in Eteron’s survey: the positive responses reach 98% (“Yes” and “I know what the term means”).

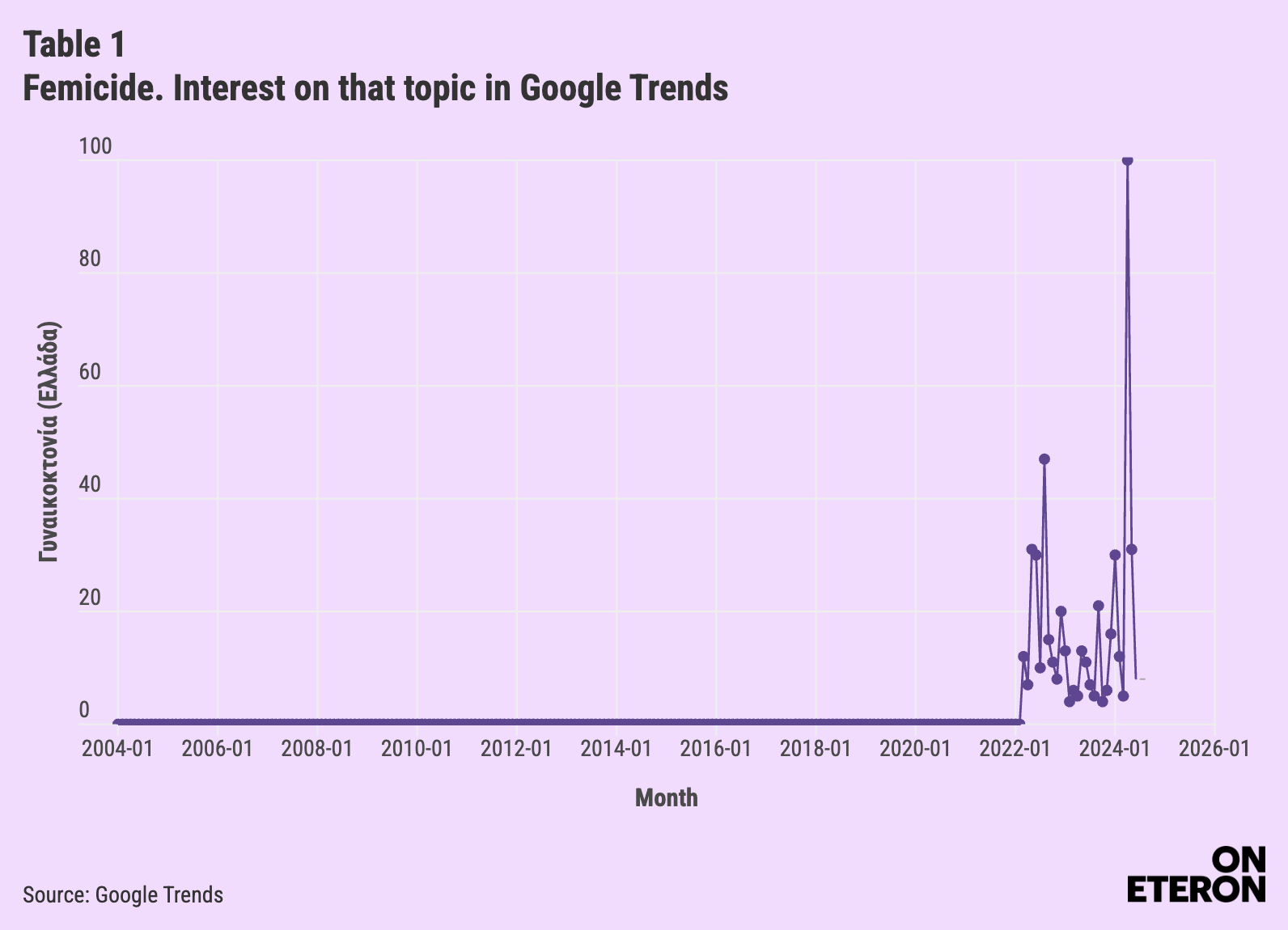

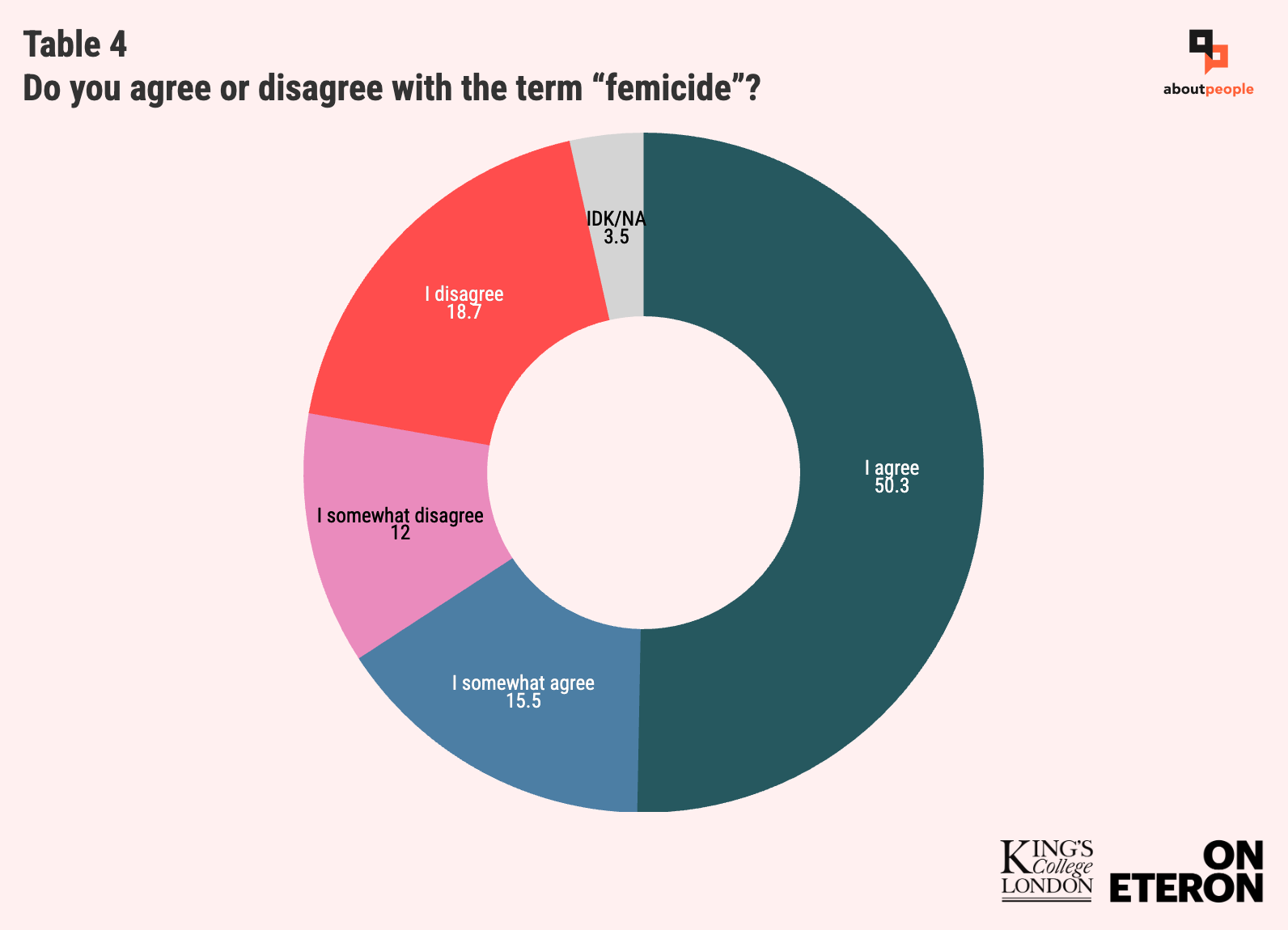

The above statement is confirmed in a variety of fields, both in public life and, of course, in several of the survey’s questions. The widespread use of the terms “toxic masculinity” (66%), “patriarchal society” (95%) and “femicide” (95.9%) argues in favour of Martha A. Ackelsberg’s observation. Although, it is a significant finding that perhaps the most important analytical concept in feminist theory (i.e. “patriarchal society”) is so prevalent in Greek society, this paper shall focus on the term “femicide”. There is a strong interest in this particular phenomenon, reflected strongly in Google searches in Greece from 2022 onwards (see Table 1). It is worth mentioning that this interest is recorded one year after January 2021 and the outbreak of the “Greek #MeToo movement”, when two-time Olympic champion Sophia Bekatorou revealed that she was sexually assaulted in 1998 by a high-ranking executive of the Hellenic Sailing Federation.

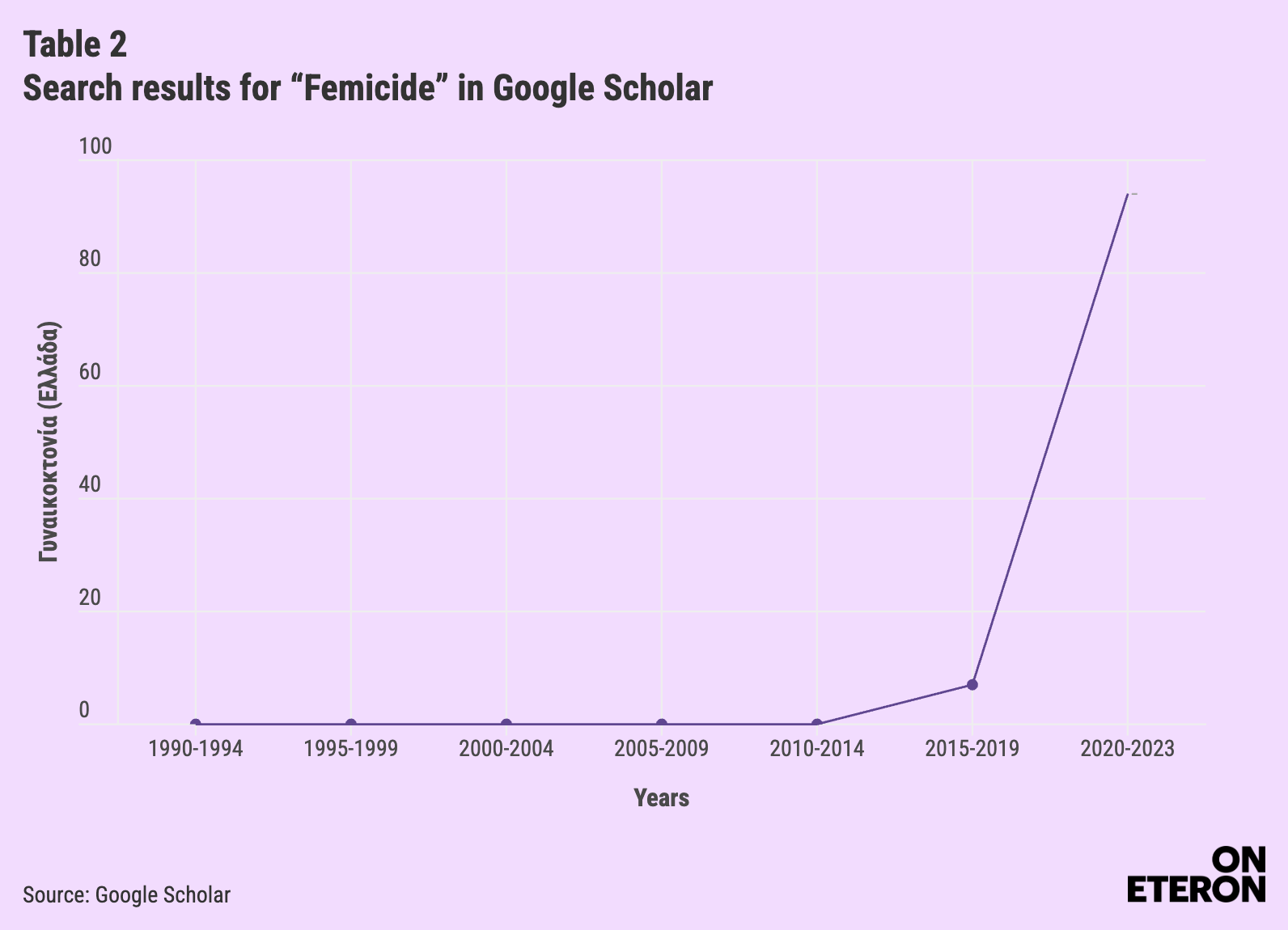

During the same period, there is also a significant increase in domestic research interest in issues related to the phenomenon of femicide (see Table 2). Thus, there is a horizontally increased interest, both socially and scientifically, in a phenomenon that may not be new to Greek society, but for many decades it was not given the importance it deserved.

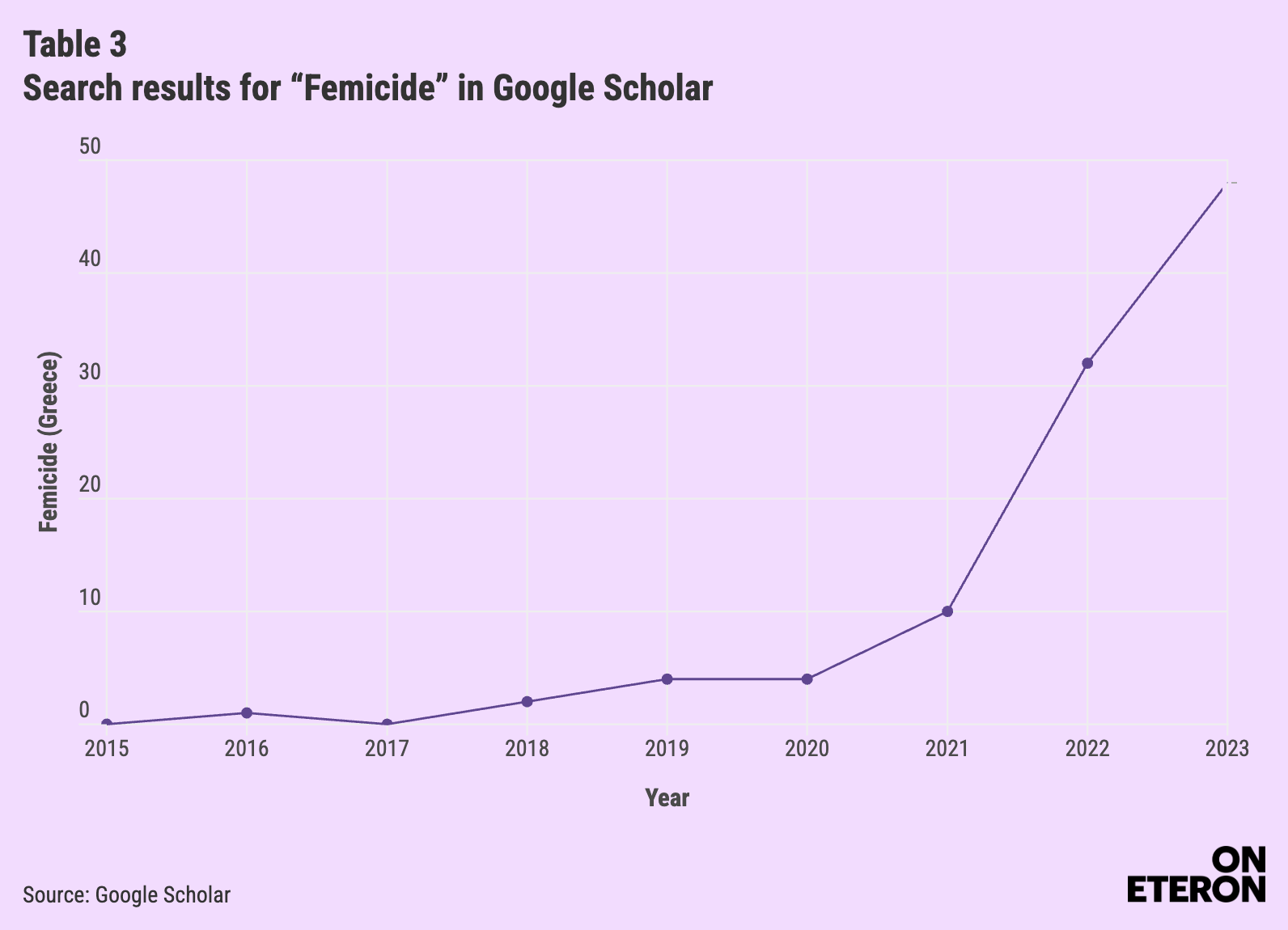

More specifically, results between 1990 and 2014 show zero research activity on the phenomenon of “femicide” in Greece, a fact that suggests a lack of interest or appreciation of the issue as an important research field during this period. However, between 2015 and 2019 we can observe an initial increase with 7 results, which reflects the emergence of interest regarding this particular topic. Then, between 2020 and 2024, there is a large boost with 102 results, indicating a significant increase in research activity and interest around this issue. If we take a closer look at the bibliographic activity, we can see that the rise in references to this term is mainly observed from 2021 onwards (see Table 3).

At this point, it is crucial to note that this trend is not confined to Greece, but is rather an international phenomenon. If one looks at the international literature, they’d find that there’s evidence supporting the conclusion that overall there has been a more intensive study of the femicide phenomenon in recent years. However, the above observation, combined with the fact that 95.9% of Greeks have heard of the term “femicide” and even state that they know its meaning, are indicative of the feminist movement’s capacity to push issues higher on the agenda. This is further evidence that feminist movements have been able to successfully turn issues that were previously perceived as private matters, such as domestic violence and reproductive rights, into mainstream issues of public discourse and ultimately public policies (Ackelsberg, 1992; Gelb & Palley, 1987).

More specifically, the feminist movement has been instrumental in securing reproductive rights, particularly in the United States, with the recently overturned landmark Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade (1973) making abortion legal nationwide. Similarly, in Britain, the feminist movement was able to push through important legislative changes that helped to reduce the gender pay gap (Equal Pay Act) and ensure fair treatment for women in several professions (Mazur, 2002, p. 98). In Spain, the socialist government (PSOE) was pressured by the movements and introduced a ban on workplace harassment in the 1989 labour code reform. Of course these are only some of the victories of the feminist movement in public policy making. Yet they illustrate the movement’s ability to bring an issue into the public sphere and then push for institutional change.

Could the femicide phenomenon evolve into such an issue? Although this term appears in the scientific literature relatively recently, in 18 Central and Latin American countries – with some variations – the term “femicide” (femicidio/feminicidio) has been turning into a legal term since 2007 (Gkoni-Karabotsou, 2021). In terms of public policies, this translates differently in each country, as the way the term is established also differs. Often it is not a penal term, nor are the underlying roots of the problem addressed. Furthermore, the UN and the World Health Organisation (WHO) have adopted the term, with the European Union following suit. As a result, in recent years there has been an increasing focus on gender-based violence in the public policy domain in a number of countries. Moreover, as mentioned earlier, in the case of Spain, the feminist movement has for decades been able to move issues such as gender-based violence from the private to the collective sphere. Similarly, in Greece, there have been initiatives taken as early as 1985 with the establishment of the General Secretariat for Gender Equality, now called the General Secretariat for Equality and Human Rights.

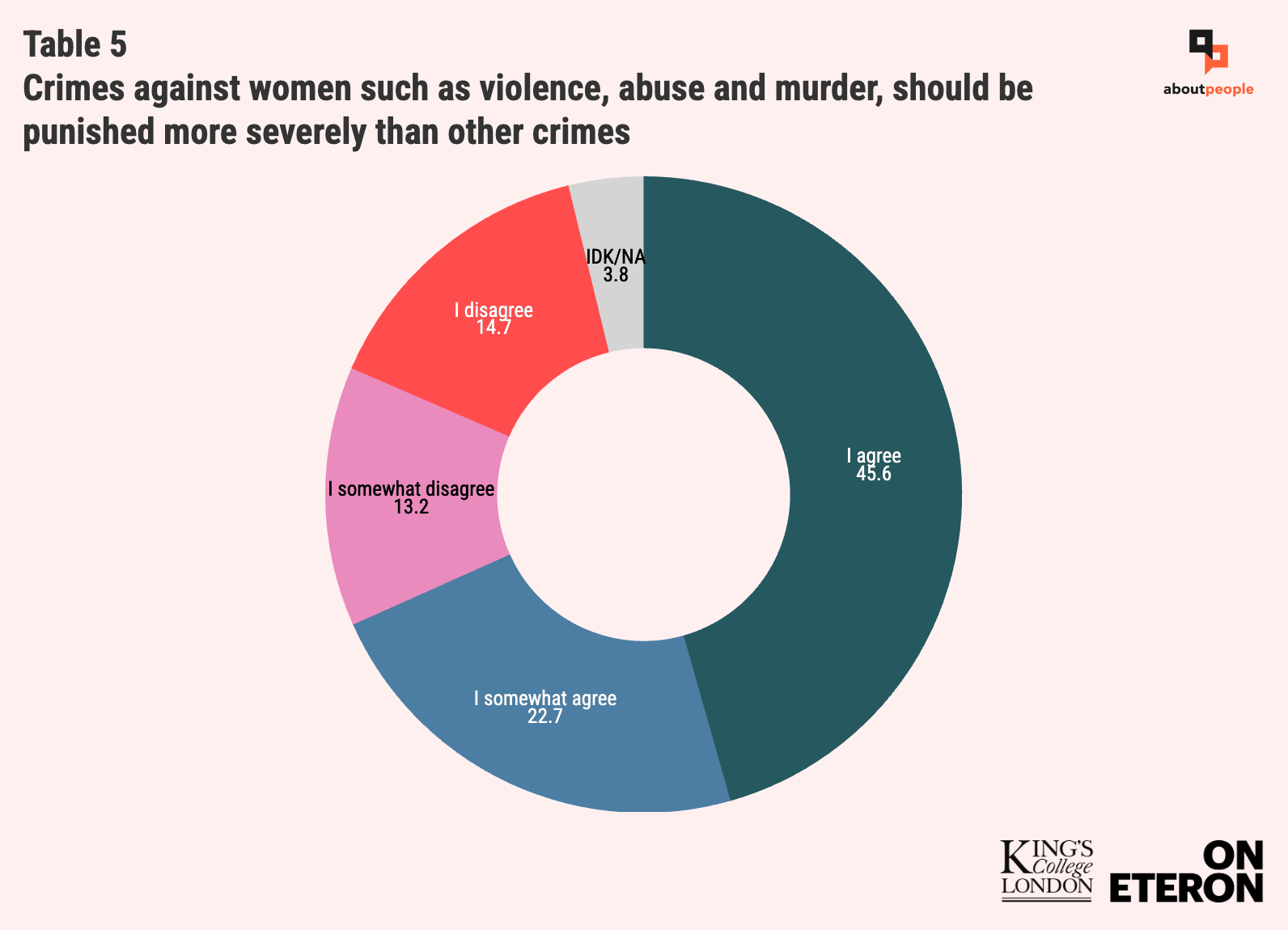

But is there scope for even bolder moves? In simpler words: has the time come for legal recognition of the femicide phenomenon in Greece and for the development of a comprehensive plan to tackle it? For this to happen, it is crucial that both a necessary and a sufficient condition be met. The necessary condition, in terms of response and change in public policy (Soroka & Wlezien, 2010), is met: The basis for strong popular legitimacy of a coherent plan to address the phenomenon exists. Eteron’s survey found that 65.8% agree with this condition (Agree & Somewhat Agree), while 79.4% believe that it is more likely for a woman to be physically abused. What is even more pivotal is that the majority (68.3%) agree that “crimes against women, such as violence, abuse and murder, should be punished more severely than other crimes”. Is the same true of the sufficient condition? This converges on the notion of “congruence” between the parties involved, and more specifically between the state and society. As mentioned above, with regards to society, there is horizontal acceptance of the fact that there is a problem of gender violence and femicide in Greece.

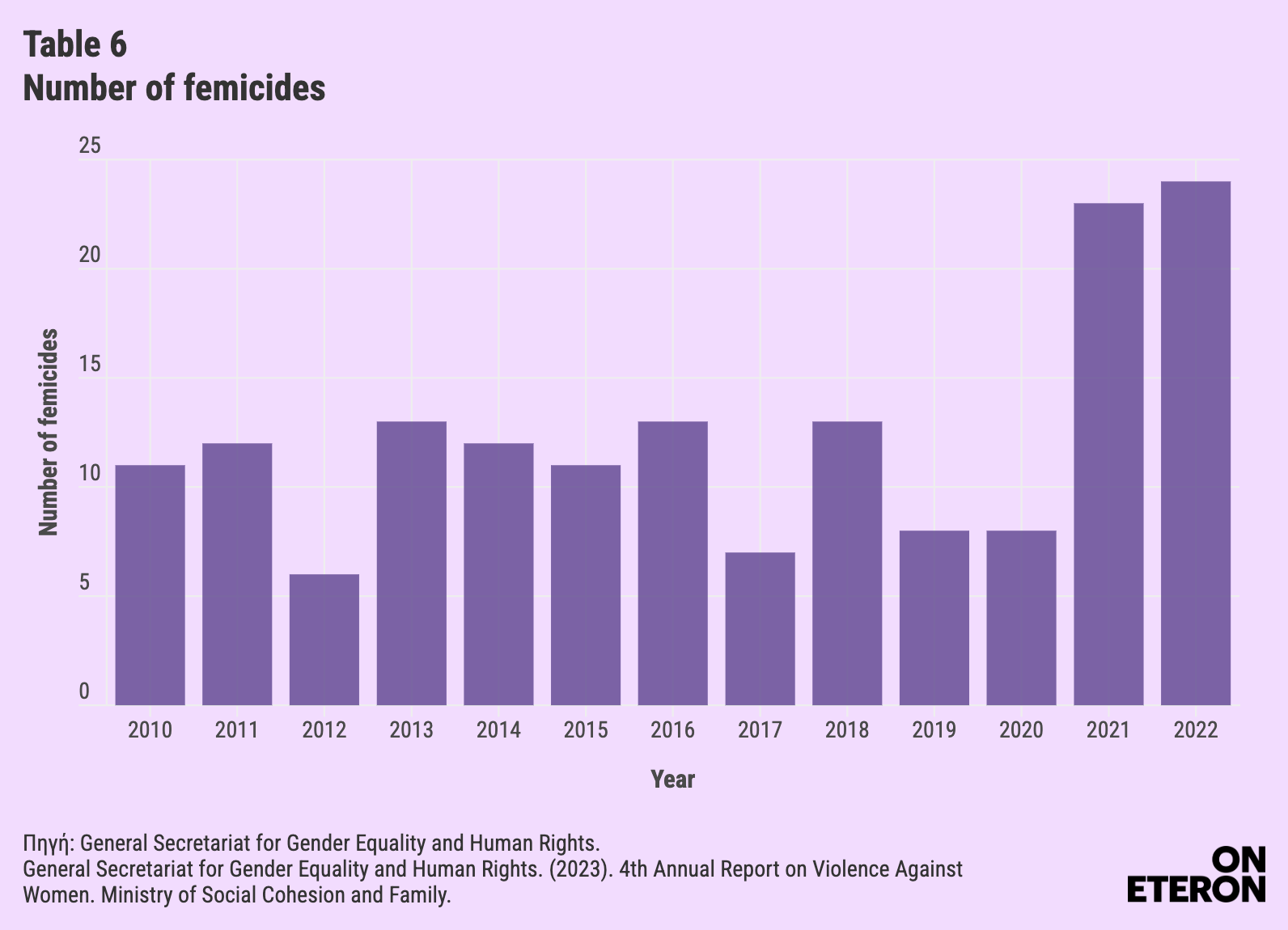

However, although the issue is recognised and there is a clear tendency within society towards understanding the gendered nature of certain crimes, as reflected in the demand for stricter sentences, institutions still have several important steps to take in order to turn some of the demands of the feminist movement regarding gender-based violence into public policies. With the number of femicides being on the rise (see table 6) according to the Greek Police data cited in the report of the General Secretariat for Equality and Human Rights (2023) and the increasing public concern about this issue, it is clear that the road to more initiatives addressing gender-based violence issues and greater responsiveness to the demands of the feminist movement is open.

However, although the issue is recognised and there is a clear tendency within society towards understanding the gendered nature of certain crimes, as reflected in the demand for stricter sentences, institutions still have several important steps to take in order to turn some of the demands of the feminist movement regarding gender-based violence into public policies. With the number of femicides being on the rise (see table 6) according to the Greek Police data cited in the report of the General Secretariat for Equality and Human Rights (2023) and the increasing public concern about this issue, it is clear that the road to more initiatives addressing gender-based violence issues and greater responsiveness to the demands of the feminist movement is open.

But what are the demands of the local feminist movement on gender violence and femicide? Do they all result in public policies? What has the General Secretariat for Equality and Human Rights already done in this direction? These are all key questions that deserve to be answered, in subsequent analyses. However, if there is one takeaway from the above text, it can be summed up in the following sentence: Thanks to the Greek feminist movement, everyone now acknowledges that there is indeed an issue of gender-based violence in the country and that the time has come to take more measures and to push for bolder and more coherent policies to tackle this phenomenon.

Ackelsberg, M. A. (1992). Feminist Analyses of Public Policy. Comparative Politics, 24(4), 477-493.

Diotima. (2024, January 24). Femicide: The leading cause of death. Retrieved from https://diotima.org.gr/gynaikoktonia-i-proti-aitia-thanatoy/#:~:text=%CE%A0%CE%B1%CE%B3%CE%BA%CE%BF%CF%83%CE%BC%CE%AF%CF%89%CF%82%2C%20%CE%BF%CE%B9%20%CF%80%CE%AD%CE%BD%CF%84%CE%B5%20%CF%87%CF%8E%CF%81%CE%B5%CF%82%20%CE%BC%CE%B5,%CE%A1%CF%89%CF%83%CE%AF%CE%B1%20%CE%BA%CE%B1%CE%B9%20%CF%84%CE%B7%20%CE%9D%CF%8C%CF%84%CE%B9%CE%B1%20%CE%91%CF%86%CF%81%CE%B9%CE%BA%CE%AE.

Gelb, J., & Palley, M. L. (1982). Women and public policies. Princeton University Press.

General Secretariat for Gender Equality and Human Rights. (2023). 4th Annual Report on Violence Against Women. Ministry of Social Cohesion and Family. Retrieved from https://www.isotita.gr

Gkoni-Karabotsou, A. (2021, September 3). The legal recognition of the crime of femicide: Comparative overview of relevant legislative initiatives in Central and Latin America. Syntagma Watch. Retrieved from https://www.syntagmawatch.gr/trending-issues/h-nomikh-anagnwrish-tou-adikhmatos-ths-gynaikoktonias-sygkritiki-episkopisi-twn-sxetikwn-nomothetikwn-prwtovouliwn-sthn-kentriki-kai-latiniki-amerikh/

Mazur, A. G. (2002). Theorizing Feminist Policy. Oxford University Press.

Radford, J., & Russell, D. E. (1992). Femicide. the politics of woman killing.

Soroka, S. N., & Wlezien, C. (2010). Degrees of democracy: Politics, Public Opinion, and Policy. Cambridge University Press.