Βetween neoliberalism and state | Τhe wavering Greek identity

Contents Index

0. Introduction Note

2. “Words” and ideological currents: The centre of gravity in the Centre/ Centre Left/ Left

3. Social-democratic and leftist financial ideals: topics with a wide reach within society

4. Yes to a competitive state. Also yes to small and medium-sized enterprises

5. Yet economic liberalism is here. Topics with a wide reach within society

6. The Greeks’ opinions regarding the inner logic of financial ideals

Conclusions: Towards a new balance

Introduction Note

Research goals

Eteron/aboutpeople’s major research is conducted during the long-term health and economic crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. An important element of said long-term critical circumstances was the massive intervention of the state, which assumed the responsibility of setting and directing sanitary measures for the population’s protection, as well as the financial aid of businesses and households.

The principal aim of this research was the documentation of the citizens’ opinions on matters concerning economic preferences and values, with the main focus of the investigation being the possibility of reinforcing state-oriented economic ideas, as a result of the pandemic, at the expense of directions and values originating from the paradigm of economic liberalism. At the same time, there was an attempt to paint a picture of the population’s sentiments on inequality and injustice within Greek society.

The fact that the research was conducted almost two years after the pandemic hit the globe, adds value to its conclusions. Nevertheless, the planning of this research (the focus and range of the questionnaire, an array of questions that facilitated a multi-dimensional approach of the subject matters) had a broader goal: to render possible – with unprecedented detail – the mapping of the basic structure of the public opinion’s preferences and values on economic and social justice-oriented issues. Thus, the re-establishment of the central and relatively stable axes that constitute the Greek economic-political culture in the long run adds a certain value to the survey, which transcends the unprecedented circumstance of the pandemic crisis.

The present analysis

The following brief presentation -it is indeed brief given the data volume that the research contains- focuses on the power dynamics and the difficult and unsteady balance between economic liberalism and social-democratic/ leftist ideals (or economic anti-liberalism ideals).

Firstly, we will explore the citizen’s opinions on the basic ideological currents that exist within Greek society. Then, we will inclusively present the subject fields where there seems to be a dominance of social-democratic and leftist economic ideals and then proceed to do the same with the subject fields that are dominated by the economic liberalism ideals. On that end, we’ll look into the distinct aspects of the Greek citizens’ preferences, such as the role that they assign to the State as a promotional agent for the competitiveness of the Greek economy or, respectively, of small and medium-sized businesses. Additionally, we’ll intend to clarify their points of view on topics relevant to fundamental admissions and values that belong to the core of either economic liberalism or the leftist economic ideals. Finally, we will compare the current findings to the ones from the period prior to the pandemic, in order to better understand the ever-present dynamic in the points of view of the Greek population.

The approach will focus exclusively on the relation between (neo) liberal and state-oriented ideals (for a more thorough presentation of the entirety of the research findings, see Petros Ioannidis’ article for Eteron). We will emphasise on the bigger picture and the “main trends”. There are many important “side-findings” that the reader may find in the research’s main body, but, for length purposes, they won’t be the focus of this report.

1. The Framework

One can say of the Greek political system that from 1981 till the elections of July 2019, the Left, Centre-Left and the Centre have been the overall predominant political forces. During said period, in every single election, the collective percentage of the non-right political parties was always over 51% (the lowest rates have been 51.13% in 1990, 51.94% in June 2012 and 52.05% in 2019) while in the most favourable elections was near or over 60% (indicative examples: 1981: 61.71%, 2009: 59.54%, September 2015: 59.06%) 1. For the most part, in the years after the regime change in Greece, the majority of the people voted for and embraced the ideology of the Centre-Left or the Left. 2.

Still, in strictly ideological or value terms, mainly since the 90’s, there has been a medium-scale weakening of the leftist or state-centred ideas and a significant reinforcement of views and priorities that are closer to economic liberalism. A preference and values base was therefore formed that gave a lead to economic liberalism, but it was within a framework of a balanced financial culture with strong social-democratic and leftist elements.

This general tendency, in which state-oriented and market-oriented ideals coexisted, didn’t change during the financial crisis of 2008-2009, a crisis that many saw as a crisis of economic liberalism and its exaggerations. Nor did it change during the period of the left shift in the Greek political party system (2012-2015). According to the findings of “What do the Greeks think” (DiaNEOsis, 2016), the “SYRIZA era” and the majority disdain of the memorandum politics, didn’t bring any significant shift in terms of people’s financial or social preferences. SYRIZA won the elections, but didn’t win in the field of financial ideals and values. 3

This divergence is indicative of the significant autonomy of the political sphere compared to the one of financial ideals, and even more indicative of the remarkable stability of the Greek population’s financial preferences. To quote Nikos Marantzidis and Giorgos Siakas “The foundations of the core beliefs of the public opinion are not shaped in a day. They’re built through complex and long term financial, political and cultural processes” 4

Nothing lasts forever, though. The external shoques, such as the pandemic and the financial crisis that followed, often work as major crossroads that overturn cognitive and value standards, thus contributing to steer ideal and value systems towards other directions.

The Eteron research extensive questionnaire focused on financial and social justice issues, thus intending to trace the dynamic lines of Greek society’s value profile, as it’s been shaped after two years of the pandemic crisis and financial unrest. The findings “speak” of the prevailing of a mixed and greatly contradictory culture, that is at the same time economically liberal but also state-centred. A culture whose characteristic trait is the disunion and the fragmentary nature of the elements that compose her. The direction though, compared to the pre-pandemic period, verges more towards the Left. The centre of gravity of the citizens’ financial preferences and values has shifted – though not decisively – towards ideas that are more in line with priorities of social -democratic, left and state-centred type.

2. “Words” and ideological currents: The centre of gravity in the Centre/ Centre Left/ Left

In diagram 1, one can see the lead that words and terms usually associated with the centre/ social-democratic and leftist political vocabulary have, according to the public’s evaluation. Ecology (with positive opinions from all participants), socialism, social democracy and liberalism refer to structured ideological and political currents and are accepted by a great majority of the public. The same goes for the “centre”, that is a more ambiguous term, as it describes less of a political ideology and more of a “middle ground” political stance in the Left-Right axis, which in Greece is partially linked to the centre political party tradition. In contrast, neoliberalism bears a strongly negative charge (positive views: 30.7%, negative views: 50.1%).

It is interesting to observe the level of acceptance of terms that are more affected by the fluctuations of political rivalry. The term “Left” has an overall negative ranking (good: 39.4%, bad: 47.7%) but still, it’s viewed a lot more positively than the term “Right” (good: 25.7%, bad: 59.8%). The term “radical left”, though, has a particularly negative evaluation from the vast majority of the population (good: 20.3%, bad: 63.9%).

Communism, nationalism, populism and the far-right are also in the negatively evaluated part of diagram 1. A couple of remarkable points would be the resilience of the influence of communism (good: 19.2%) and the extent of the participants with positive views on nationalism (17.2%), even though the negative ones are significantly more. Populism received a very negative rate (good: 8.5%, bad: 80.6%) with citizens who place themselves in the centre-left and the centre-right expressing the most negative opinions (respectively 84.6% and 86.6%).

Diagram 1

The term “socialism” is viewed more positively by older generations (55-64 years old: 65.6% and 65+: 68%) and less so by younger people (17-24 years old: 47.5%, 25-34 years old: 52.3%). Additionally, socialism has a greater reach in the centre-left (85%), left (76.9%) and central (53.8%) sides of the Left-Right axis, and also amongst the middle class, in terms of salary range.

Especially if we look at the class self-placement of the participants, the lower middle class (63.9%), the middle class (58.5%) and the working class (56.9%) view the term more positively. In total, the widely positive response to the term (good: 59.1%, bad: 27.2%) shows that the strong left and centre-left political tradition that exists in Greece since the regime changed in 1974, is still active and has a strong influence in our country.

The term “social-democracy” has surprised us. Even though it doesn’t have significant roots in the Greek political party map, based on the groups that give it a positive rating, we could say that it has a clearly more mainstream content, compared to socialism. Just like the latter, it represents something “good” mostly for the older age groups (55-64 years old: 60.3%, 65 +: 64.8%) and its differentiation from the term “socialism” gives it higher ratings among the upper class and the upper middle class (59.3%) and lower ratings among the working class (44.1%). Based on income, it has better ratings among the wealthier groups (over 2000 Euro: 68.1%, 1501-2000 Euro: 65.7%). In general terms, we could say that the tendency for positive feedback is inversely proportional to the social and economic status of the citizens, something that adds a more “bourgeois” element to this finding. It also enjoys an extended horizontal ideological and political support: Centre-left (69.2%), Centre (50.7%), Centre-right (50.1%), Left (47.5%, Right (29.3%). This term that is viewed positively by so many different groups, has a sociological centre of gravity in the upper and the upper middle classes and its political-ideological centre of gravity lies between the Centre-left, the Centre and the Centre-right.

The term liberalism (a term that represents something “good” for 46.2% of the population and something “bad” for 38.4% of them) is more popular amongst the younger age groups (17-24 years old: 54,6%, 25-34 years old: 47.7%), the citizens who place themselves in the Centre-right (64.3%), the Right (59.1%) and the Centre (45.4%) of the political and ideological spectrum and the upper and the upper middle classes. This particular term, despite its “fluid” and less strict usage – compared to other terms such as neoliberalism, communism etc.- and despite its historical link to the liberal Centre tradition prior to the dictatorship, it now belongs, though not exclusively, to the political vocabulary of the extended Right and Centre-right. Its posite ratings mostly come from the right and centre-right sides of the axis.

The same goes for neoliberalism (positive ratings: 30.7%). It enjoys increased acceptance amongst the higher earning classes (over 2000 Euro: 46.6%, 1501-2000 Euro: 37.4%) and among those who place themselves in the Centre-right (48.7%) and the Right (43.3%), while it has a significantly smaller horizontal acceptance (Left: 9.2%, Centre-left: 15.8%, Centre: 29.8%) than the terms “liberalism” or “socialism”. Regardless of whether there is a (theoretic, historic, conceptual) close notion link between the two terms, the practical political meaning that was assigned to them, as we can deduce indirectly by the (political, ideological and demographic) groups that rate them positively (and negatively), has a centre-right and a right charge. Practically, “liberalism”, a term with a wide notions content and broad acceptance, and “neoliberalism”, a term with many negative connotations, are seen by citizens who place themselves to the right side of the political continuum as their main reference ideological currents. They’re part of their ideological territory.

To sum things up, the findings of Diagram 1 describe a political culture that’s mostly oriented towards the ideals and tradition of the Centre-left (mostly) and the Left (secondarily). They also describe the strong impact -though clearly they’re a minority- of centre-right (mostly) and right (secondarily) ideological currents. The dynamics of the Greek political culture are leaning towards the Centre-left and the Left. As it has been the case since the regime changed in 1974.

Diagram 2

The data shown in Diagram 2 and Index 1, confirm and at the same time elaborate on this tendency towards the Centre-left and the Left. Once the question becomes more specific and concerns a significant – amongst many alternatives – political choice (not just if a term represents something “good” or not), the answers’ range confirms and at the same time alters the first general image. In “which ideological approach guarantees a combination of faster and more just growth”, social democracy leads with 20%, followed by socialism with 17.1%. On the other hand, the profile of those who opted for social democracy, though demographically it’s still an interclass case, significantly focused in middle and upper-middle classes, one can see that it’s mostly centred towards the Centre-left, on this particular question.

More importantly, though, the profile of those who picked “socialism” significantly changes focus and acquires a more left oriented centre of gravity.

INDEX 1

So, in the “‘socialism’ team”, there’s an over-representation of citizens that place themselves on the Left (38.3% – a percentage that’s more than double the average) and the Centre-left (33.2% – a percentage that’s almost double the average) while there’s an under-representation (a bit more than on Index 1) of the Centre (14%). The combined evaluation of the sum of the findings above, strongly asserts the argument that the Centre-left and the Left have a lead within the Greek political system. This lead is also depicted in the data shown in Diagram 3.

This centre-left and left lead, though, that has been a more or less permanent trait of the Greek political system since 1981, only describes the general impact that’s mostly political or to a degree also ideological. It does not describe the people’s ideas and value choices. The influence of the state-oriented or leftist preferences and values as well as that of liberal economic preferences aren’t shown in the previous findings. That’s why in the following lines, we’ll trace the power dynamics between economic liberalism and “anti-liberalism”.

Diagram 3

3. Social-democratic and leftist economic ideals: Topics with a wide reach within society

In core topics such as the evaluation of capitalism, the unequal distribution of wealth, the need to tax the highest earning classes, the flexible employment forms, the duration and the amount received in social welfare benefits, privatisations, the budget allocated for the National Health Service, the link between strong trade unions and salaries as well as desired level of state intervention in order to reduce market impunity, the (total or relative, depending on the topic) majority of the population expresses preferences that are closer to the priorities set within the ideological domain of the Left and Centre-left.

Also the stance according to which in the future, core fields of social and economic activities (such as education, healthcare and pensions) should mainly fall under the responsibility of the public sector, along with all utility companies, is powerful and does not leave any space for ambiguous diagnostic assertions. More specifically, when it comes to education, healthcare, pensions and the water supply, the state-oriented alternative gains referendum-like characteristics (over 84%), as the central-left and the left, the central-right and the right, seem to lean towards it. The above-mentioned sectors are regarded as the natural epicentres of state responsibility. This belief enjoys extensive and horizontal ideological-political support. Also, energy, land transportation but also the privatised banking sector is thought to be better off in the hands of the public sector in the future (in the banks’ case, it’s a close call with 51.6% against 39.8% who want to keep it privatised).

The preference shown in all levels of public education against the private equivalents is prominent and worthy of a special mention (Diagram 4). The preference in favour of the Public sector is grand and it’s even more prominent that the respective preference expressed in past surveys.

DIAGRAM 4.

In total, the assignment of the main responsibility to the State for seven out of the nine sectors examined in this research (should be the responsibility of the public sector: education, health care, pensions, water supply, energy, land transport and the banking system – though that last one was a close call. For the responsibility of the private sector: mobile phone networks, air transportation – also see Index 4) is an indicator of the impact of ideas that stem from the state-centred model of values and political priorities and also it shows the lack of trust in solutions that emphasise on private entrepreneurship and the market. Whatever the reasons may be for this mass preference towards the public sector, the people’s choices trace a solid and extended “area” of sectoral policies that the (neo)liberal model won’t be able to access easily.

The Left-Right axis is systematically linked to the expression of different opinions in the thematic fields of Index 2. In particular, the evaluation of capitalism, the perception of an unequal distribution of wealth in favour of the big businesses, the desire to tax the rich in order to achieve a redistribution of income, the link between powerful trade unions and salaries and privatisations are topics that provoke different answers depending on where citizens place themselves politically and ideologically.

Still, the dipole Left-Right does not produce a generalised across the board polarised division of preferences, as in several areas, a significant part (or even a majority) of citizens who place themselves to the Right/Centre-right adopt ideas that originate from the state-oriented preference model. Therefore, the political parties of the Left and those of the Right are internally heterogeneous with contradictory and -partly- self-conflicting preferences and values.

4. Yes to a competitive state. Also yes to small and medium-sized enterprises

INDEX 3

It’s very interesting to analyse the public opinion on the strategic role of the State in promoting competitiveness. 68.9% believe that “Without an appropriate state strategy, Greece will never become a powerful export economy”, while 22.8% think that “Only private businesses can turn the Greek economy into an exporting force”. Therefore, according to the public opinion, the State is mainly the strategic player that could promote competitiveness in the global market.

Yet, at the same time, more than two thirds of the participants want the State to support small and medium-sized enterprises because “they’re the backbone of the economy and they sustain the Greek family”, while only a small percentage (4%) wants for the State to support large corporations in order for them “to grow bigger and be competitive on a global scale” (Index 3). Those findings are in line with the reality -and the relevant culture- of small-scale ownership and small-sized enterprises that are the dominant model in Greece and also, it is consistent with the distrust towards big corporations that has been documented on multiple occasions. Still, despite the fact that for the majority of the participants competitiveness represents something “good” (71.9%) and the fact that they agree that the State should have a central role in promoting competitiveness, the collective desire for supporting small-sized enterprises probably shows that the public opinion hasn’t reached a mature decision regarding the internationalisation of Greek companies. Maybe this stance (yes, the State is the key “player”, but it’s all about small and medium-sized enterprises) on one hand reflects the fact that the Greek exporting businesses are clusters that are detached from the rest of the economy and society and on the other hand, it becomes evident that the topic of global competitiveness isn’t central within the Greek public sphere. Given the absence of an “achievement-based capitalism” similar to what exists in other small countries with strong exporting performance (Greek shipping is an exception – though it’s an industry that isn’t based in Greece), this contradictory stance seems to “make sense”. In any case, Index 3 depicts the importance of the State for the participants, as well as their distrust towards capitalism, mainly expressed in their stance against large corporations.

5. Yet economic liberalism is here: Topics with a wide reach within society

On the opposite side of ideas based on the state-centred model of political and values’ priorities, the trust invested in solutions focusing on private entrepreneurship and the markets is very high or the relative majority in the topics shown on Index 4. In key topics of the liberal economic mentality, or topics inspired by it – such as competitiveness, market economy, the reduction of taxation even if that would mean less state welfare, the abolition of the civil servants’ tenure, the perception that civil servants are a privileged group, trickle down economics- the impact of ideas that lean towards neoliberalism is particularly strong. Especially concepts and opinions strongly linked to capitalism and neoliberalism, such as “competitiveness” (71.9%), “market economy” (64.9%) and the preference of an economic model that’s mostly based in the free market (52.7%) they receive better rates of approval than the source concept of “capitalism” (24.1%) or “neoliberalism” (30.7%). Those majority opinions are also popular among a significant percentage of the Centre-left and the Left. Especially in the cases of “competitiveness” (Left and Centre-left: 60.7%), the reduction of taxation in order to allow for the growth of businesses (Left and Centre-left: 62.7%) and the opinion that civil servants are a privileged group (Left and Centre-left: 54%). The political permeability of those ideas that are leaning towards capitalism and/or neoliberalism is impressive. Just like with the findings of Index 2, we can see the strength of the Left-Right division and at the same time the limits of its divisive energy.

6. The Greeks’ opinions regarding the inner logic of financial ideals

In addition to including them in the main synopsis graphs (Indexes 2 and 4), it is worth analysing in more detail a distinct group of questions. They’re questions that intend to understand the citizens’ opinions on topics that belong, to a larger or a more limited extent, to the core of economic liberalism as well as that of left ideologies. Opinions on personal freedom, personal effort, social collaborations and collectivity, the nature of inequality, the creation of wealth and the effectiveness of the public sector are part of (or at least near) the core that forms these two great historical currents, liberalism and socialism.

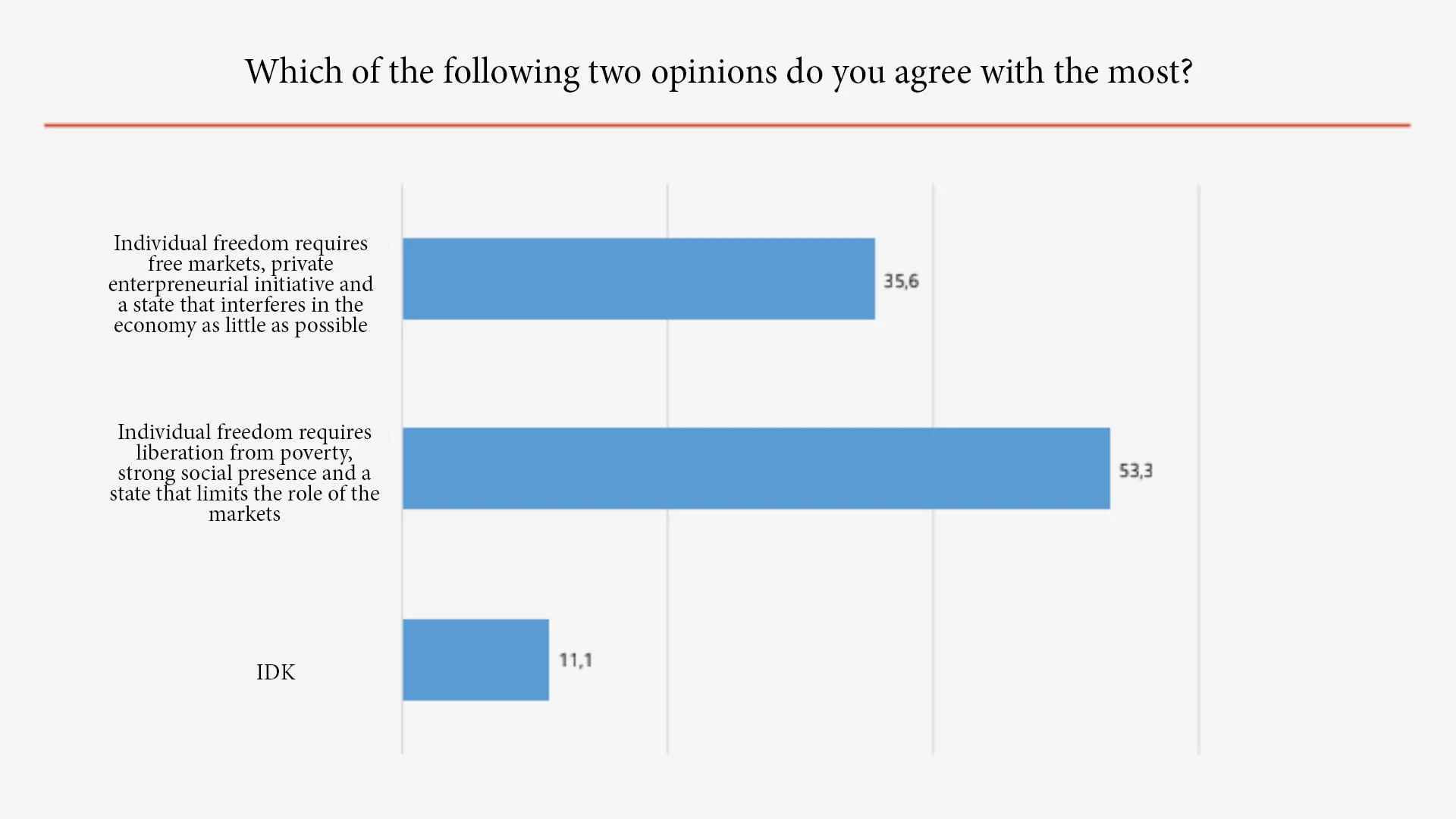

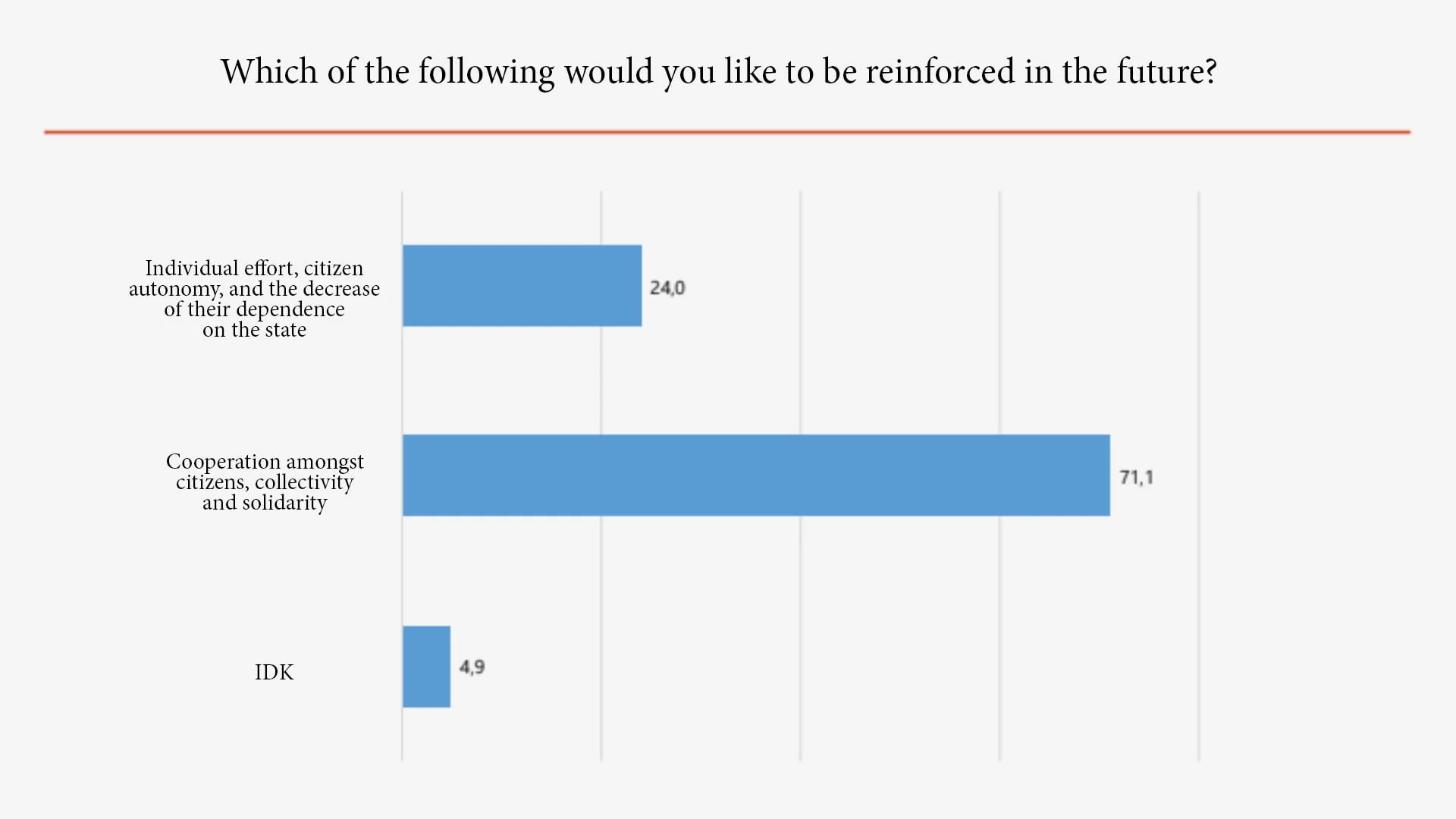

For 53.3% of the population, the concept of personal freedom is linked to the liberation from poverty, to a strong social support system and to a State that limits the markets. On the other hand, for a significant yet minority 35.6% of the population, freedom means free markets, private initiatives and State interventions to be limited to the bare minimum. Of the people that participated, 71.1% would prefer for citizens’ collaboration and solidarity to be strengthened in the future, while just 24% hope for more individual effort, citizens’ autonomy and decrease of their dependency from the State.

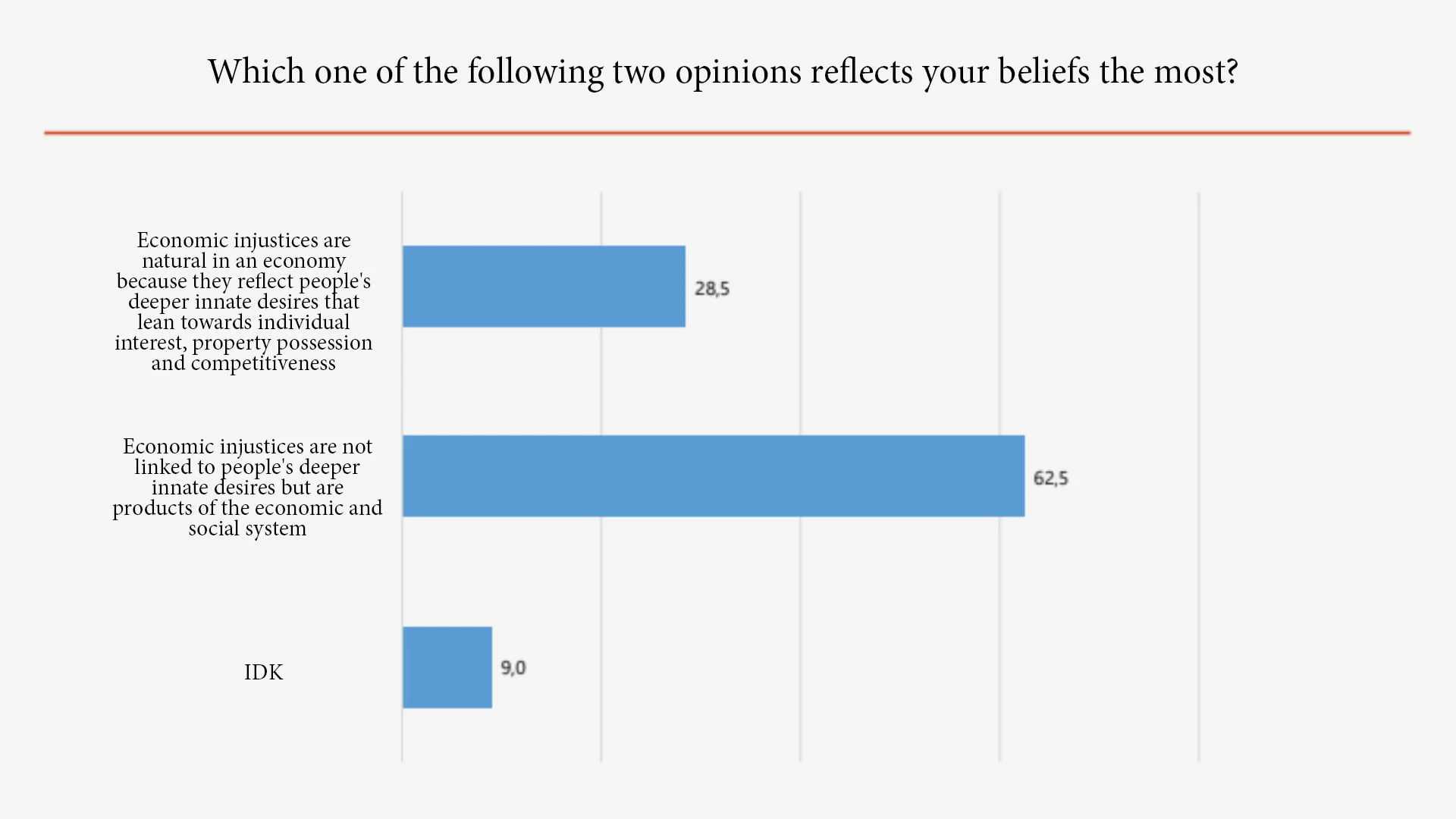

Respectively and cohesively, for 62.5% of the citizens, economic inequalities exist because of the economic and political system and are not inherent in human nature “that has a tendency towards personal interest, accumulation of property and competitiveness”. The latter viewpoint belongs to 28.5% of the participants. Without entering into the difficult discussion regarding the “individual” and the “collective” or the foundations of personal freedom, we can state that at least at a first glance, the Greeks’ opinions and values lean more towards a mentality that isn’t compatible with economic liberalism.

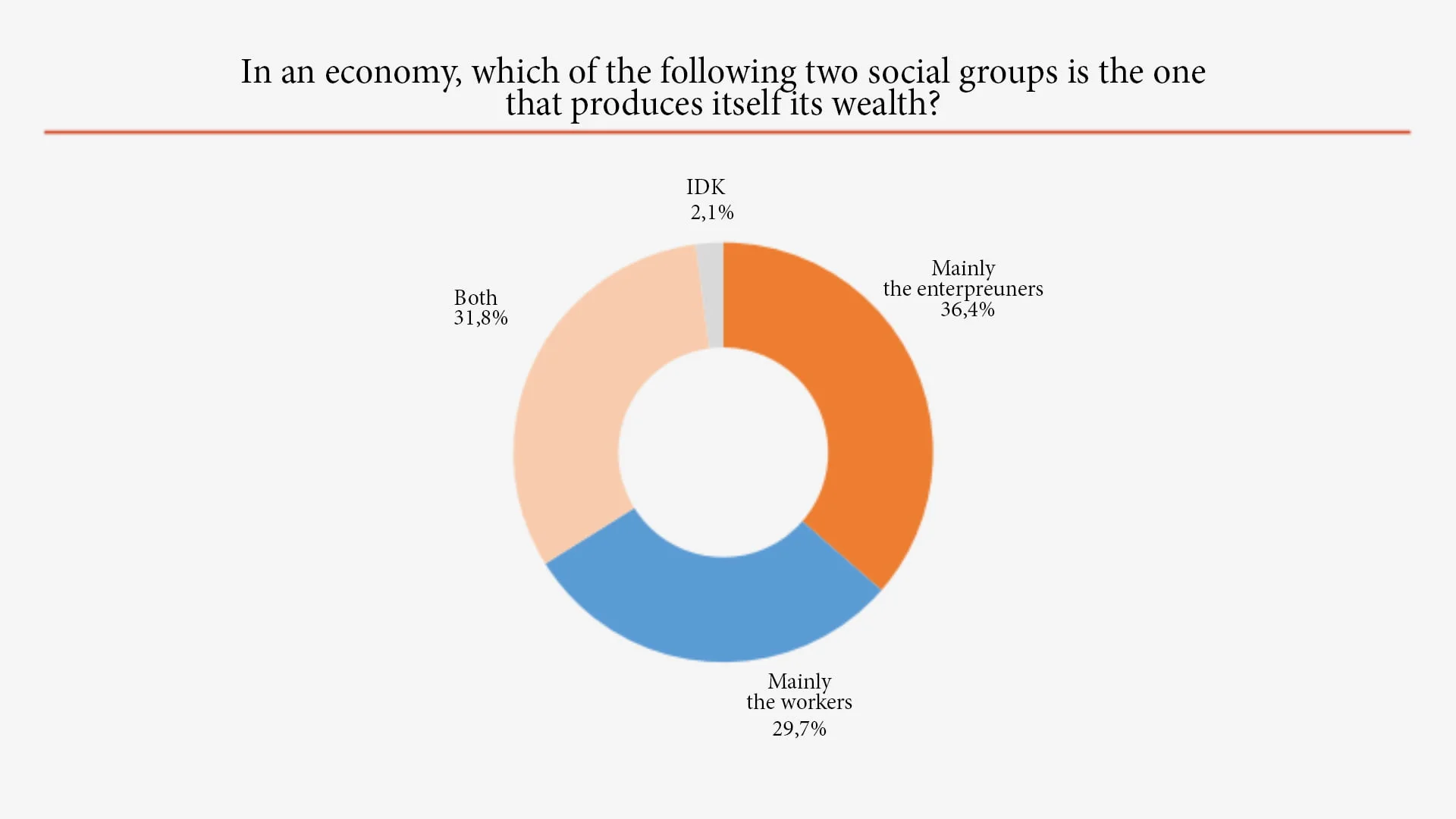

Yet things are more complex. When asked “who produces the wealth”, 38.4% of the participants believe that it’s “mostly business people”, while 31.8% believe that it’s business owners and workers to an equal extent and finally, a significant yet minority 29.7% -given that this is a society that rates socialism very highly- believes that it’s the workers that mainly produce wealth.

DIAGRAM 5

Therefore a basic statement of the most leftist theories, not just marxism, doesn’t have enough support in the general population. It is interesting that the 17-24 age group believes that wealth is produced by business owners (46%). This belief is largely shared by business owners and freelancers (42.8%), the unemployed (39.3%) and employees of the private sector (38.7%), though this last group is the one with the highest percentage of people who believe that it’s the workers that produce wealth (35.4%). Clearly, the participants that work in the private sector, just like the people who are looking for work, are the most favourably inclined towards entrepreneurship – something that deserves a special mention. Politically, those who place themselves at the Left, believe that it’s “mostly the workers who produce the wealth” over two times more than the general population (64%), while the centre-left supports this statement at a rate of 44.9%. On the other hand, this viewpoint is shared only by 23.9% of those who place themselves at the Centre and it’s even less amongst the Centre-right (18.6%) and the Right (14.1%). So, in what concerns the four questions that to a greater or a lesser degree involve “core” opinions and viewpoints, the final image is mixed, though there’s a clear lead of social-democratic and leftist ideals.

Therefore a basic statement of the most leftist theories, not just marxism, doesn’t have enough support in the general population. It is interesting that the 17-24 age group believes that wealth is produced by business owners (46%). This belief is largely shared by business owners and freelancers (42.8%), the unemployed (39.3%) and employees of the private sector (38.7%), though this last group is the one with the highest percentage of people who believe that it’s the workers that produce wealth (35.4%). Clearly, the participants that work in the private sector, just like the people who are looking for work, are the most favourably inclined towards entrepreneurship – something that deserves a special mention. Politically, those who place themselves at the Left, believe that it’s “mostly the workers who produce the wealth” over two times more than the general population (64%), while the centre-left supports this statement at a rate of 44.9%. On the other hand, this viewpoint is shared only by 23.9% of those who place themselves at the Centre and it’s even less amongst the Centre-right (18.6%) and the Right (14.1%). So, in what concerns the four questions that to a greater or a lesser degree involve “core” opinions and viewpoints, the final image is mixed, though there’s a clear lead of social-democratic and leftist ideals.

The answers in a relevant questions’ group are also equally interesting. 48.8% of the population agree with the statement “More large profit-producing businesses lead to more benefits for the general community” , while 44.4% disagree. In this case, one of the essential stances of economic liberalism, the trickle down effect, is supported by a significant and relatively majoritarial part of the population. The strongest support comes from the younger age groups (17-24: 53.2%, 25-34: 49.9%), the upper/ upper-middle class (58.4%), the middle class (52%) and the higher earling groups (1501-2000 Euro: 56.7%, over 2000 Euro: 59.3%). This opinion is shared – based on political self placement – the Right by 64.6%, the Centre-right by 63.8% and the Centre by 52.2%, while it’s a lot less popular on the left side of the political continuum (Left: 28.4%, Centre-left: 28.6%).

Also the standard neoliberal (and conservative) opinion that “When the state provides substantial benefits, it teaches its citizens not to make an effort” is accepted by the majority within Greek society (50.6%). The strongest support for this statement comes from the over 65 years of age (63.7%), the upper/ upper-middle class (67.4%), business owners and freelancers (63.7%), those who earn over 2000 Euro per month (80.7%) as well as those who place themselves at the Centre-right (67.7%) and the Right (70.2%).

The similarly liberal viewpoint that “the unemployed could find work if they really wanted to” is accepted by 45.1% of the participants, while 50.7% disagree with that statement.

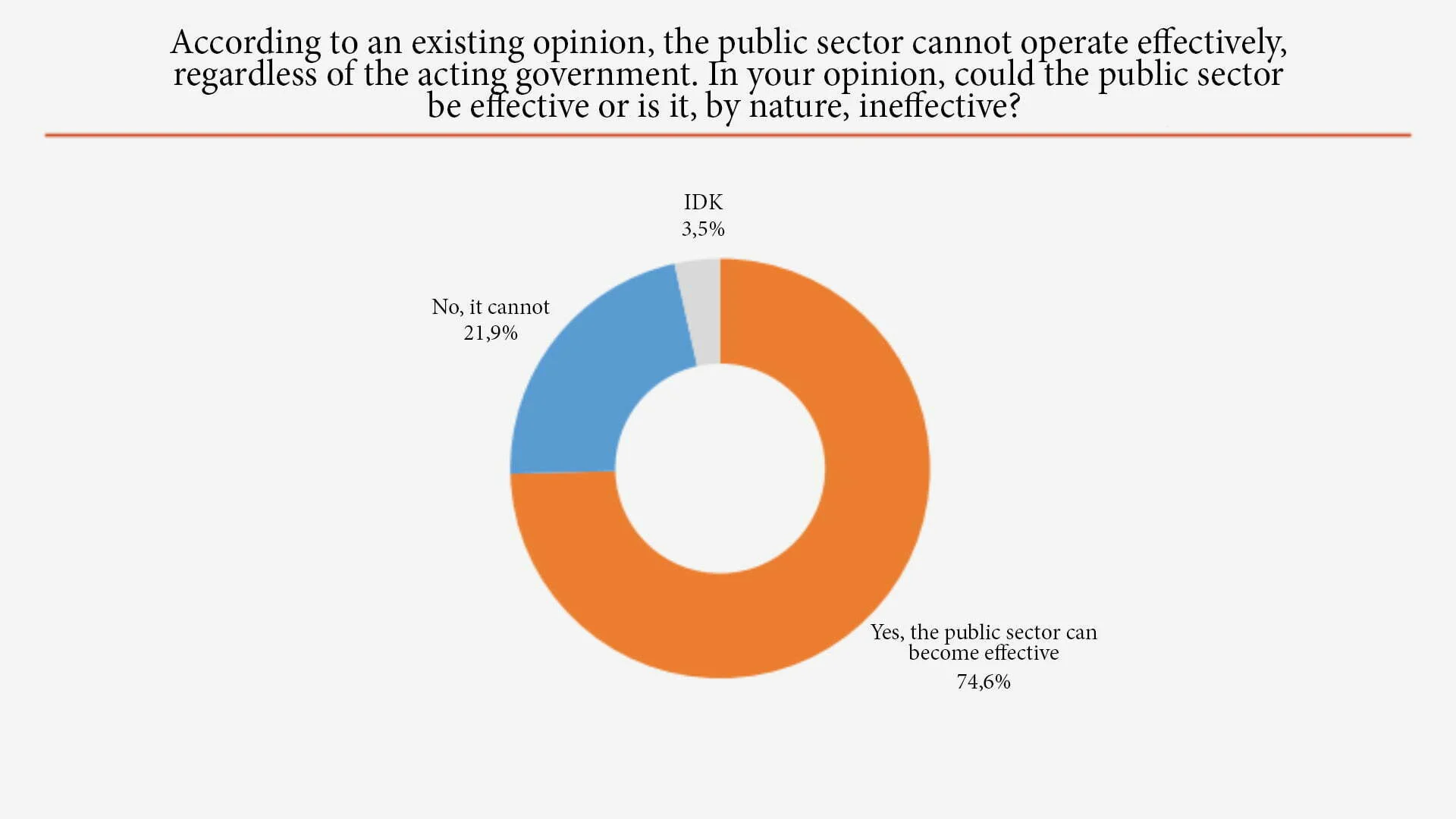

On the other hand, only 21.9% agree with the liberal statement that the public sector “could never be effective” (74.8% disagree). Still, we believe that this viewpoint, given the demographics of its supporters (it’s most popular amongst the over 65 years of age, the working class, the lowest earning groups but also those who place themselves at the Right) is only partially a part of the division between economic liberalism and economic anti-liberalism. Maybe the close-up experience with the Greek public services or even the feeling of exclusion from them better explains the participants’ opinion regarding the potential effectiveness of the public sector.

Overall, in four out of the seven questions of this section (we didn’t take into consideration the question regarding the effectiveness of the State), the findings depict an advantage of ideals of leftist descent. It’s not a question of numbers (how many questions there were on each side) but of the level of infiltration of each idea in the community. In the matter of freedom, the individual or the collective and the source of inequality, the wider Left ideals are more widely spread. The foundation of the notions that constitute the social fabric is closer to the Left’s world of ideals despite its mixed and heterogeneous character.

7. Comparing with the past

If the Greek population’s economic culture is shaped by two currents with competing viewpoints and ideologies, what is the power dynamic between the two after the two covid-19 years? In order to form Index 6, we picked comparable factors and made sure that the structure and the questions’ wording were identical 5. In ten out of the eleven topics that were compared (with the exception being that of trade unions), there’s an increase in the percentage that leans towards the Left, with the largest one being noted in the questions regarding the State’s interventions and State welfare. Therefore, the direction of this shift, rather than its numeric margin (that only has an indicative value, due to the different methods used by the two different survey companies) shows that there has been a change in the citizens’ preferences, compared to the time before the outbreak of the pandemic.

Of course, the political conjuncture of the two researches affects the results. The 2019 research was conducted 5 months after N.D. ‘s win at the elections, therefore it makes sense that it produced more favourable numbers for right-winged ideals. Eteron’s research, on the other hand, took place in less favourable circumstances for the ideals of economic liberalism. Therefore the different conjunctures may explain part of the participants’ differentiated preferences (especially regarding notions such as the Right and the Left, that are sensible in the political climate shifts). Still, every research is conducted within a certain conjuncture. Therefore, even though we should be cautious while drawing conclusions, the differences depicted in Index 6 are so clear that to undermine them would constitute a major interpretative error. To sum things up, the comparison between 2019 and 2021, shows a clear increase of the impact of social-democratic and state-centre viewpoints. This increase is fully connected to the external shock of the pandemic and probably also with the new role of the State – more active and caring compared to before.

Looking through findings of relative researches, and mainly the DiaNEOsis one(due to the identical wording), we can confirm grosso modo the tendency described above. I will mention some indicative examples of questions with identical wording: In April 2015 (during the peak of the SYRIZA phenomenon), 67.2% of the citizens supported the abolishment of the civil servants’ tenure (DiaNEOsis), while in 2018 the rate was 65.1% (DiaNEOsis) and in the current research it’s 63.4%. The percentage that was in favour of a better and bigger State was just 5.6% in April 2015 (DiaNEOsis), while in December 2021 it rose to 19.6%. The significant stance that “Taxation should be low even if that means there will be less state welfare” is adopted by 43.7% of the population (current research), compared to 39.2% in April 2015, but since then and till the outbreak of the pandemic, there had been a rapid and extensive increase in its popularity, possibly due to the sensation of overtaxation that was formed during the governing years of SYRIZA (April 2016: 39.2%, November 2016: 45.7%, 2017: 54.5%, 2018: 64.2%, 2019: 62%, Eteron: 43.7%).

In all the topics mentioned above, the increase in popularity of state-centred ideals is apparent and, usually, significant 6. There are several examples and what they depict is a leniency of the public opinion towards more left-winged values and preferences. If in 2015, the intervening variable was, within the financial crisis framework of that time, the SYRIZA wave and the rise to power of the radical Left, in the present time, the intervening variable is the “lengthy conjuncture” of the pandemic. In both cases there was a boost, though limited in scale, in economic ideals that are on the opposite side of liberalism.

Conclusions: Towards a new balance

In the field of economics, Eteron’s research confirms the existence of a mixed economic and political culture that combines opinions and value-based priorities of a (neo)liberal origin with more “social-democratic” and “state-centred”-leaning priorities. This dual template, which is simultaneously neoliberal and “state-centred”, produces a powerful dualism of values and beliefs.

This dualism constitutes, actually, a steady norm that has defined Greek culture since at least the 1990s. In reality, it has been the product of the debilitation of state-centred ideals and the empowerment of beliefs and priorities closer to economic liberalism after 1990.

Eteron’s extensive questionnaire that focused on economics depicted the extent of that dualism and also allowed for a firmer validation of core elements of economic liberalism as well as its economic and ideological competitors (examples: prioritising taxation decrease or the dispersion of benefits [trickle-down effect] for liberalism, the powerful conviction that the public sector should take the reins in matters of education, healthcare, pensions, water supply, etc for anti-liberalism).

The research’s second contribution would be the emergence of a new trend:

Social-democratic and leftist economical views and convictions have gained significant ground. Given that for the past 30 years at least, economic neoliberalism keeps a small yet steady lead (a lead – not dominance or reign), the boost of state-oriented economic policies – if not proved to be circumstantial due to the pandemic- balances out the interrelation of ideas and values within Greek society. One of the research’s important findings is the partial realignment with non-liberal or anti-liberal economical preferences.

This partial realignment does not constitute a subversion, however. The findings do not hint of any kind of major, in comparison to the near past, internal weakening of neoliberalism within public opinion. Nor are they indicative of a major shift. The “balancing out”, though, renders this game of ideas more wavering and with it, the identity of the Greeks.

The evaluation of the balancing dynamic requires mindfulness when one studies it. It is very much likely that the boosted popularity of state-centred and leftist ideas is due to the pandemic. Therefore, this popularity that surged along with the pandemic, could very well dissipate after the crisis ends. The only way to achieve a shift and a “level-up” would be for this popularity to keep increasing in the near future. Something that’s far from being certain.

The division between the Left and the Right structures, amongst others, the population’s economic preferences and values to an important degree and on a systematic level. However, in subject areas dominated by either one of the two ideological systems, one significant percentage (or even the majority) of the Left and an equally significant percentage (or the majority) of the Right adopt central beliefs of the opposing ideological system. The Left-Right division is powerful. It doesn’t define, however, two political wings (politically and ideologically-defined, not party-defined) that are internally homogeneous and with strongly discernible economic identities.

If Greek culture is multifaceted, mixed and contradictory, the mixing of ideas and contradictory motives of values constitute an integral aspect of both the Left and the Right. The Left and the Right differ a lot and converge considerably. This complex and mixed nature of the ideological parties underlines the relative autonomy of the world of ideas from the strongly [political] party-oriented sphere.

If the Greeks’ culture is multifaceted, mixed and internally contradictory and if that texture is a core component of its identity, then the Greek economic culture, as a distinct system of values and ideals, is neither neoliberal nor social-democratic. It’s both and -most importantly – neither.

- Unpublished data by Panagiotis Koustenis. Data post 2015: edited by Gerasimos Moschonas.[↩]

- Gerassimos Moschonas και George Papanagnou. Posséder une longueur d’avance sur la droite: Expliquer la durée gouvernementale du PSOE (1982-96) et du PASOK (1981-2004). Pole Sud, 2007, no 27. The unfavourable spread of the electoral force for the political parties of the Right from 1981 onwards, didn’t stop – for reasons that are beyond the scope of this article – the political party of Nea Dimokratia (ND), one of the most powerful political parties of the European conservative parties’ family in terms of electoral influence, to form government majority, either with or without coalitions.[↩]

- G. Moschonas, What Greeks believe: A values mapping of Greek society: Main findings, conclusions and synopsis. Athens: DiaNEOsis, 2016.[↩]

- N. Marantzidis, G. Siakas, In the name of dignity. The subversions of public opinion during the Memorandum years. Athens: Papadopoulos, 2019: p. 288.[↩]

- The signatory was a scientific consultant for the first wide-scale research conducted for DiaNEOsis (2015) and has coordinated the shaping of the questionnaire, just like in the present research.[↩]

- Regarding the term “Left” in particular, it reached a positive rating record in April 2015 (52.5%), it then crashed pretty significantly and also rapidly (November 2015: 39%, 2017: 37.4%, 2018: 33.5%, 2019:33.4%) but it’s now showing a clear improvement, according to the current research (39.4%)

[↩]