Tourism in Greece: A society that ponders on the pros and cons

1. Introduction

The phenomenon of overtourism is being increasingly discussed in public discourse as well as in academic publications, as its complex effects on local communities render it a very sensitive area of public policy. Eteron’s project “Staycation Nation” aims to look into the various aspects of overtourism in Greece, through the perspective of the locals’ perceptions. The assessment of dimensions such as quality of life, environmental protection and satisfaction with the existing economic model of tourism is crucial for the development of sustainable tourism strategies.

1.1 The impact of tourism on the economy

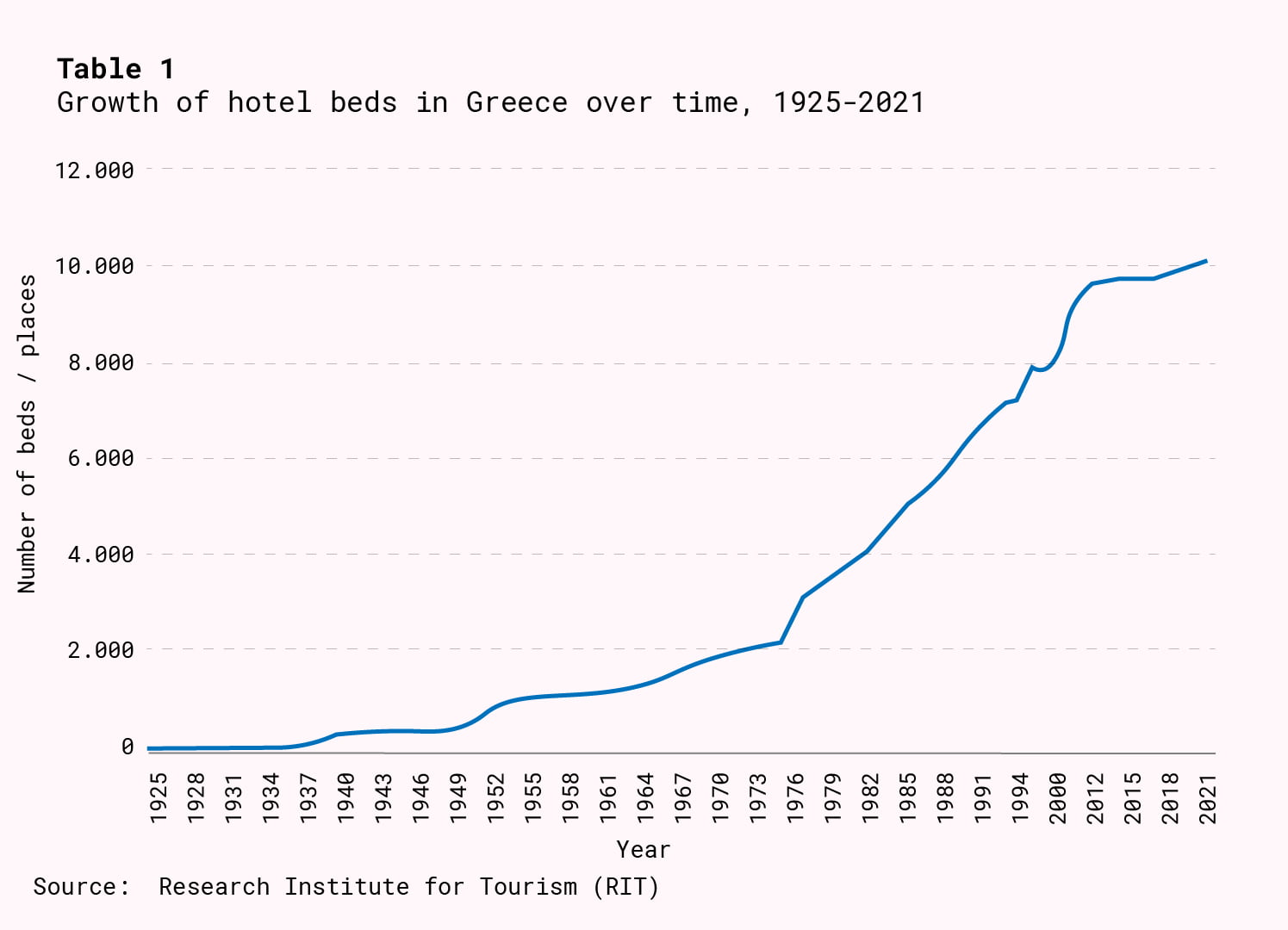

In 2023, tourism’s direct contribution to Greece’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) reached 13%, totalling 28.5 billion euros, the highest share historically for the sector to date, according to data from INSETE – the Institute of the Greek Tourism Confederation (Ikkos & Koutsos, 2024). In fact, the authors of the INSETE report point out that if we also consider tourism’s “indirect contribution through multipliers”, the relevant share increases to approximately 30% (between 28.5% and 34.3%). The continued growth of the tourism sector not only reflects its recovery after the COVID-19 pandemic, but also the country’s long-standing strategic investment in it (see Table 1). This is reflected in the fact that “travel earnings covered 63.8% of the goods balance deficit”. Finally, it is worth mentioning that arrivals reached 32.7 million in 2023 (+4.4% compared to 2019 and +17.6% compared to 2022), not including cruises, which push the number to 36.1 million arrivals in 2023.

But are the above figures enough to suggest that there is overtourism? The monoculture of tourism at the level of the economy does not necessarily imply an overtourism issue. However, before embarking on this debate, it is important to understand the meaning of this relatively recent term. Once the phenomenon is defined, it can be studied with more accuracy and precision.

1.2 overtourism: The need for a definition

Overtourism is a circumstance in which the number of visitors arriving in an area exceeds its carrying capacity, thereby reaching the maximum sustainable levels of burden, resulting in negative impact on both the environment and the local community. More specifically, overtourism can be responsible for the depletion of natural resources, increasing the cost of living and altering the local residents’ quality of life (Seraphin et. al., 2018). According to Koens et al. (2018), overtourism can be defined as “the excessive negative impact of tourism on the host communities and/or natural environment”. Negative impact includes environmental pollution, increased cost of living and housing, congestion of transport infrastructure, alteration of local identity and cultural heritage.

2. Views on the financial dimension

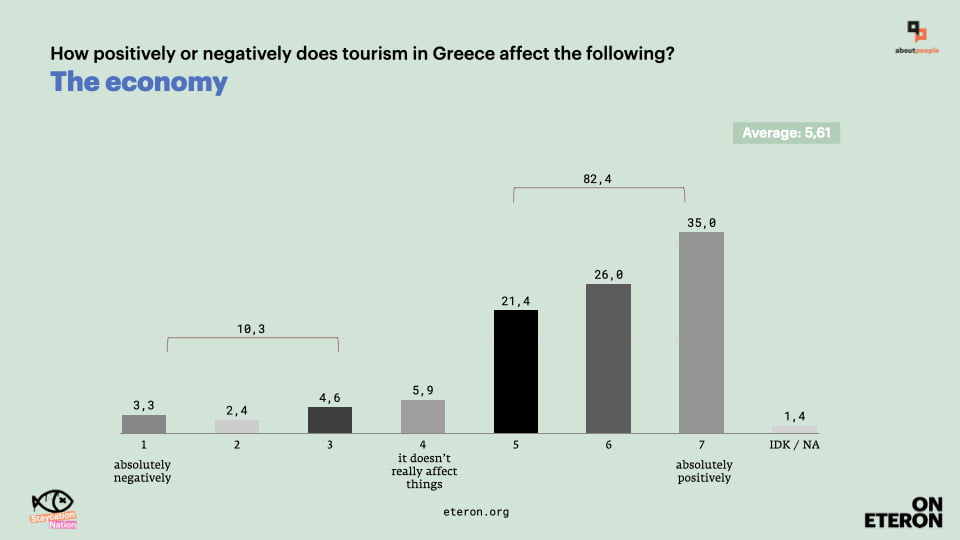

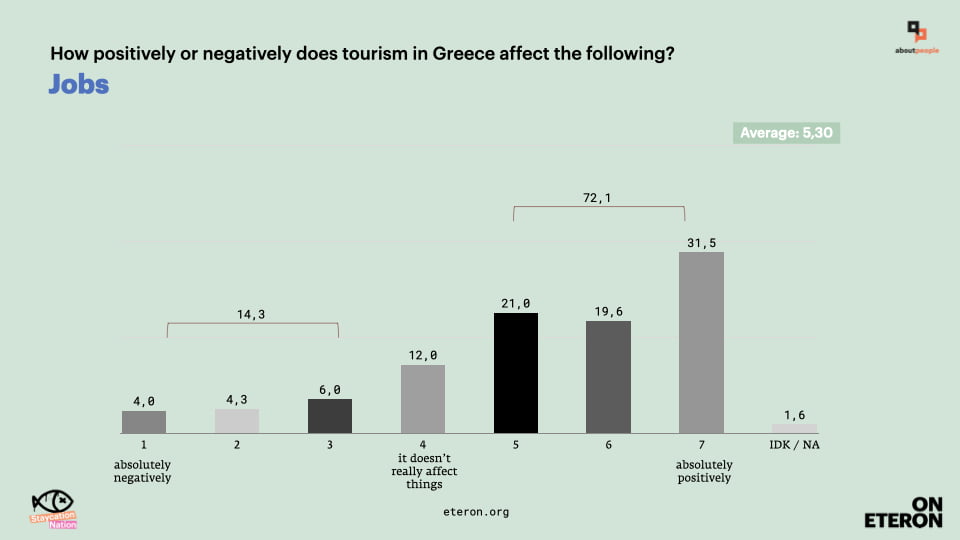

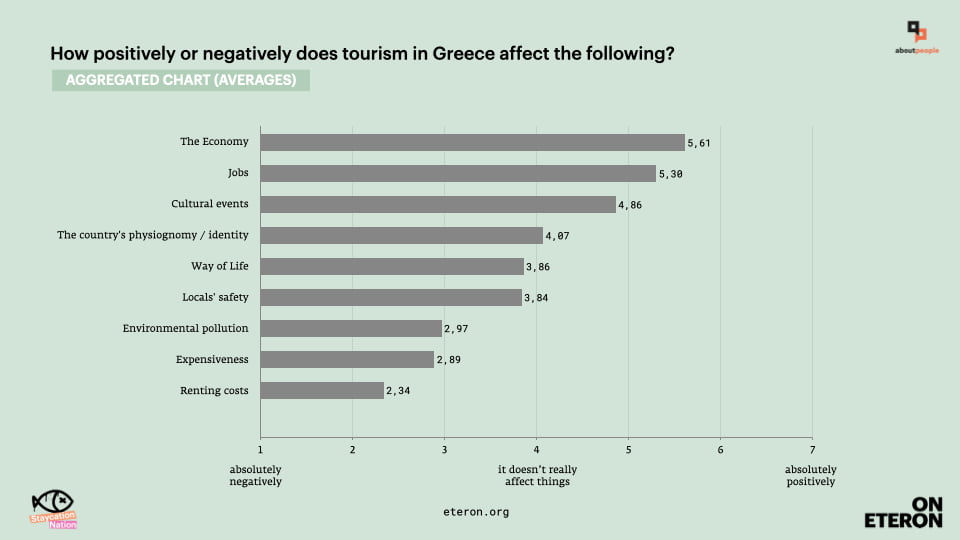

While tourism can boost local economies by creating jobs, and increasing state revenues, it can also lead to higher living costs, excessive economic dependency and ultimately – among other things – market failure, as Dwyer et al. (2020, p. 411) aptly point out. At the same time, local businesses may experience significant economic prosperity during peak tourist seasons, but this can also lead to inflation in housing and goods prices, making it difficult for local residents to afford even the basics. This is why the survey includes questions about people’s perceptions of the positive or negative impact of tourism on both the local and national economy. To examine this dimension, the participants were asked to rate the extent of positive or negative impact of tourism on areas such as the economy, jobs, expensiveness and rental costs through scale questions, scoring from 1 (“absolutely negatively”) to 7 (“absolutely positively”).

2.1 The positive impact on the economy and jobs

The survey shows that citizens are mainly positive about the impact of tourism on the economy (average: 5.61) and on jobs (average: 5.30). More specifically, in terms of the economy in general, 82.4% believe that tourism has a positive impact on the economy, while 72.1% believe that it contributes positively to the labour market as well. Of course, the above responses may also reflect a confirmation of people’s lived reality, with citizens acknowledging the critical importance of this sector for the national economy, but without evaluating whether growth based on this sector is preferable to any other. In other words, this finding shouldn’t be interpreted as a de-facto approval of the country’s economic policy. It is a field requiring further investigation.

Table 2: Assessment of the positive and negative impact of tourism on the economy

Table 3: Assessment of the positive and negative impact of tourism on Jobs/ the Labour market

2.2 Expensiveness and sky-high rents

At the same time, people feel that this economic activity is linked to an increase in the prices of goods and rents. In fact, these two categories have the lowest rating in the evaluation with the average of both variables being below 3% (see Table 3). In particular, 65.2% of the survey participants assess the impact of tourism as negative when it comes to expensiveness, while the corresponding percentage for rental costs increases to 78.7% . Of course, tourism is only one of the variables that is most likely connected to the increase in the prices of goods and rental properties, even in touristic areas. Nevertheless, these high rates do sound an alarm. The available data do not suggest that we have what Dwyer et al. (2020) describe as a market failure, but society is now concerned about the negative aspects of this particular industry.

Table 4: Assessment of the positive and negative impact of tourism in Greece

3. The environmental aspect

Secondly, the survey also focuses on the environmental impacts of overtourism, since increased tourism activity often results in pollution, depletion of natural resources and degradation of local ecosystems (Seraphin et al., 2018). Eteron’s research examines residents’ perceptions regarding the environmental impact, looking at issues such as water and electricity shortages, as well as pollution. Such questions are essential as they reveal how residents perceive the sustainability of the environment in which they live (Milano et al., 2019). Along with the natural environment, we added to the equation the issue of concern for the preservation of the cultural heritage in touristic areas and the protection of public spaces from intense touristic development (García-Hernández et al., 2017).

3.1 The damage inflicted on the natural environment

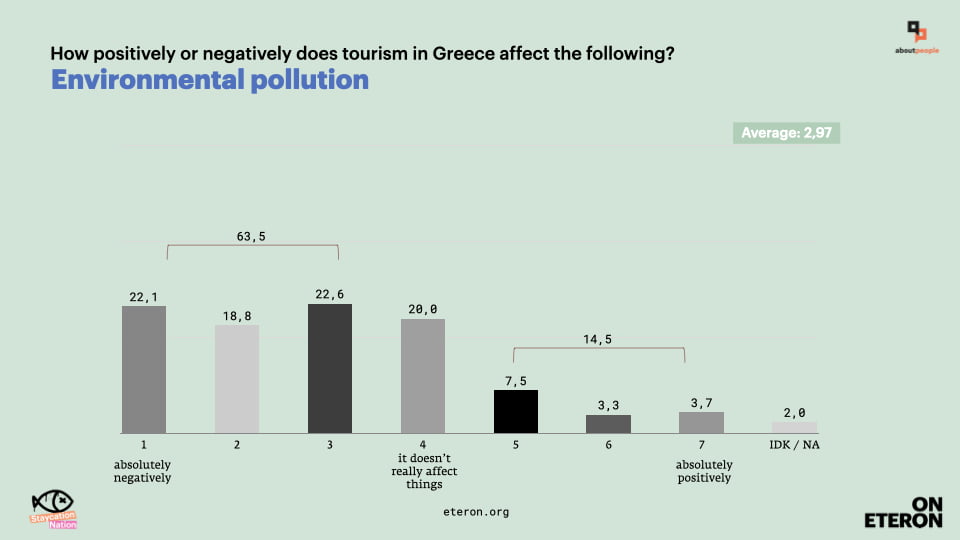

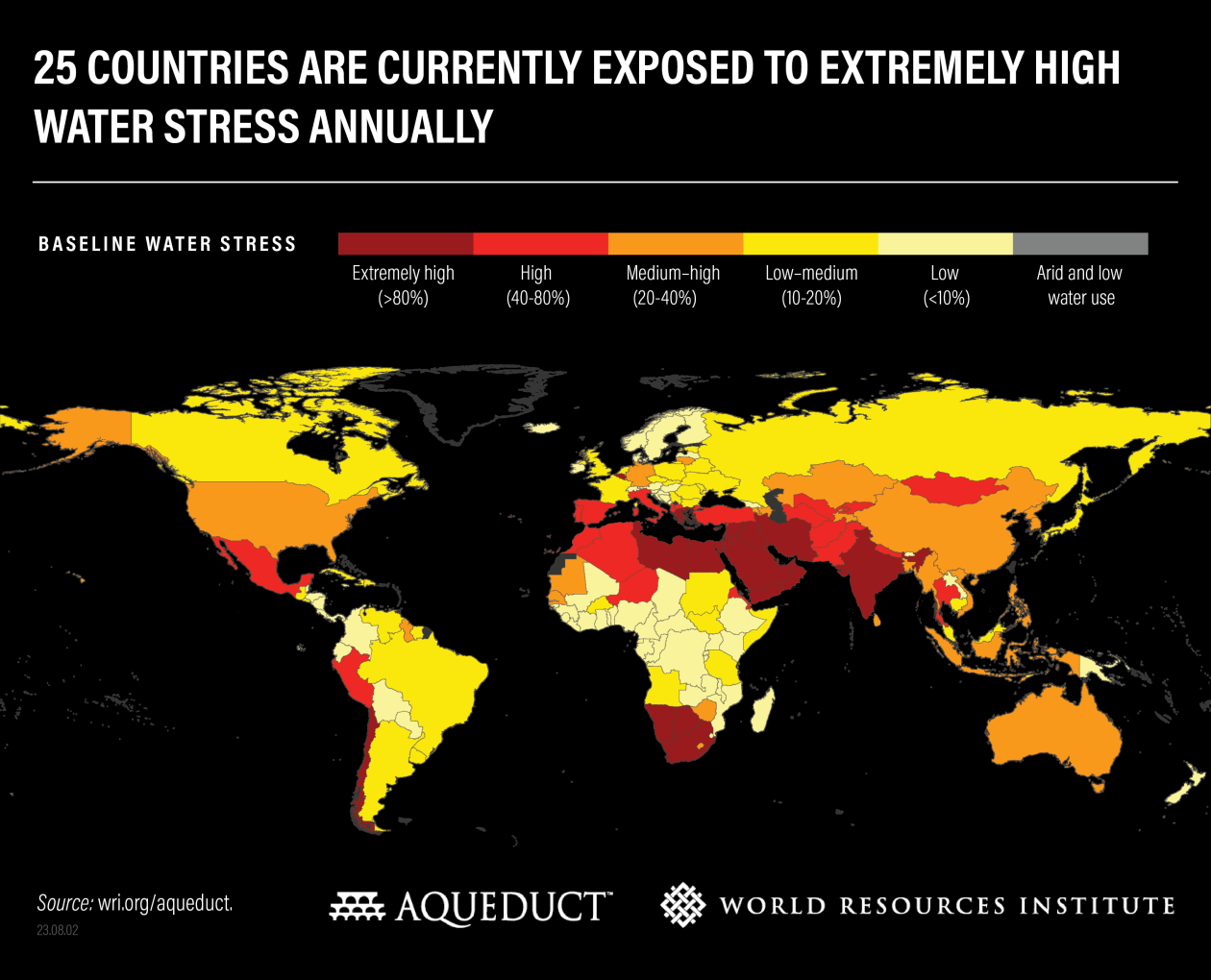

With 63.5% of the citizens acknowledging the environmental damage caused to the country, it becomes clear that in recent years Greeks have become increasingly aware of the impact that intense economic activity in this sector has on nature. Moreover, according to both the World Resources Institute (WRI) and a relevant research by Kuzma, Saccoccia and Chertock (2023), Cyprus, San Marino, Belgium and Greece are experiencing extremely high water stress (see Table 5), which is reflected in our country by water scarcity issues that several regions face during the summer (Liaggou, 2024).

Table 5: Assessment of the positive and negative impact of tourism on the environment

Table 6: World map of annual baseline water stress levels per country

3.2 The positive aspects of cosmopolitanism and its impact on public spaces

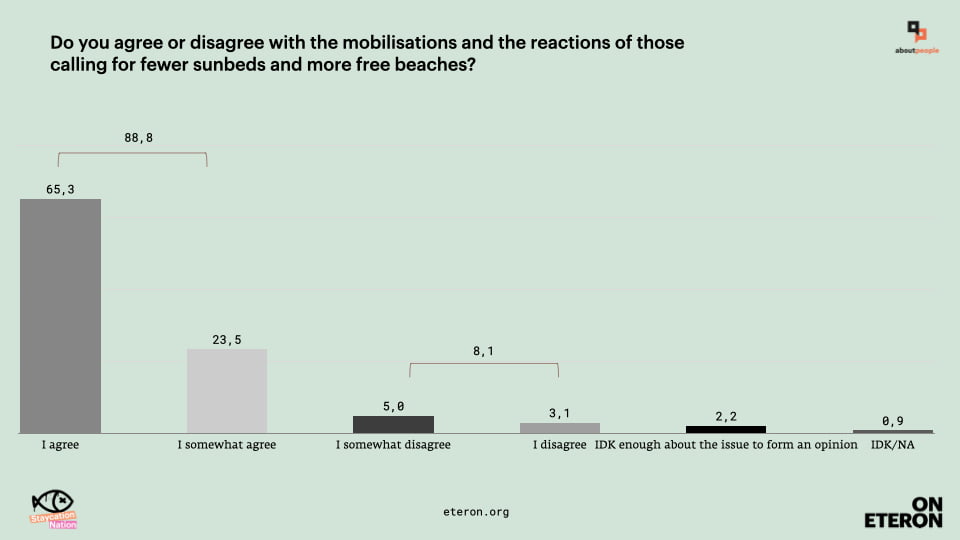

However, besides the impact that tourism has on the natural environment, the participants find both negative and positive effects on Greece’s image and physiognomy (34.5% stated tourism has a negative impact and 34.5% believe the opposite). However, there is a clear irritation regarding the impact this particular sector has on the quality of public spaces, with 88.8% supporting mobilisations for free beaches and fewer sunbeds. This is just one aspect of the perception of public spaces, which also requires further research.

Table 7: Views on the Mobilisations and Reactions demanding Fewer Sunbeds and More Free Beaches

4. Quality of life and overtourism

Another key focus of Eteron’s survey is the impact that tourism has on the locals’ quality of life in areas with high tourist traffic. overtourism can disproportionately burden local infrastructure, leading to non-functional public spaces and services, which negatively affects the daily lives of residents (Koens et al., 2018). This is why we chose to examine indicators such as overall satisfaction with life as well as individual elements that act as additional data, in order to understand the levels of people’s tolerance or annoyance.

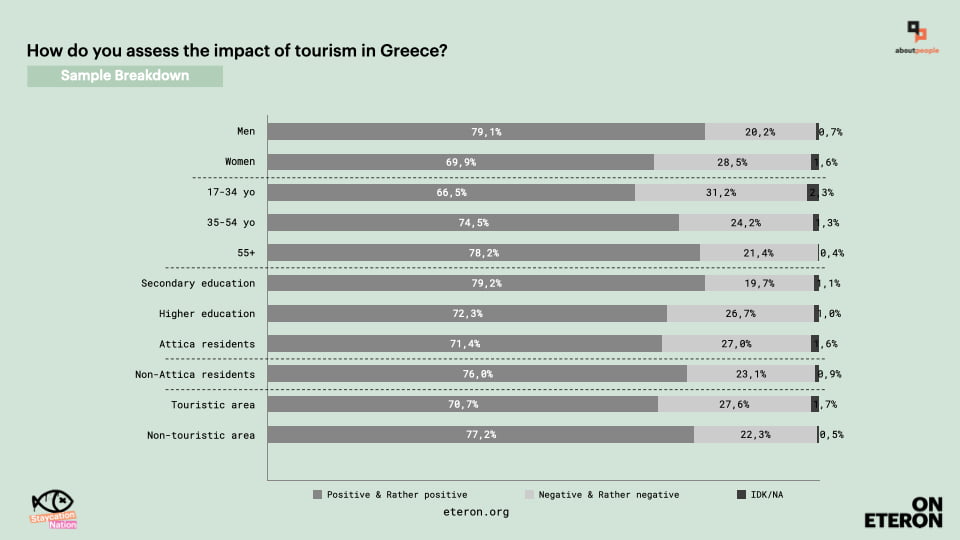

The pressure that tourist areas are under is reflected in the fact that when asked to evaluate the impact of tourism in Greece, satisfaction decreases by 6.5% amongst residents of touristic areas. It is worth mentioning that, in general, the survey does not reveal any significant differences between the responses of those living in touristic areas compared to the rest of the population.

Table 8: Assessment of the impact of tourism in Greece

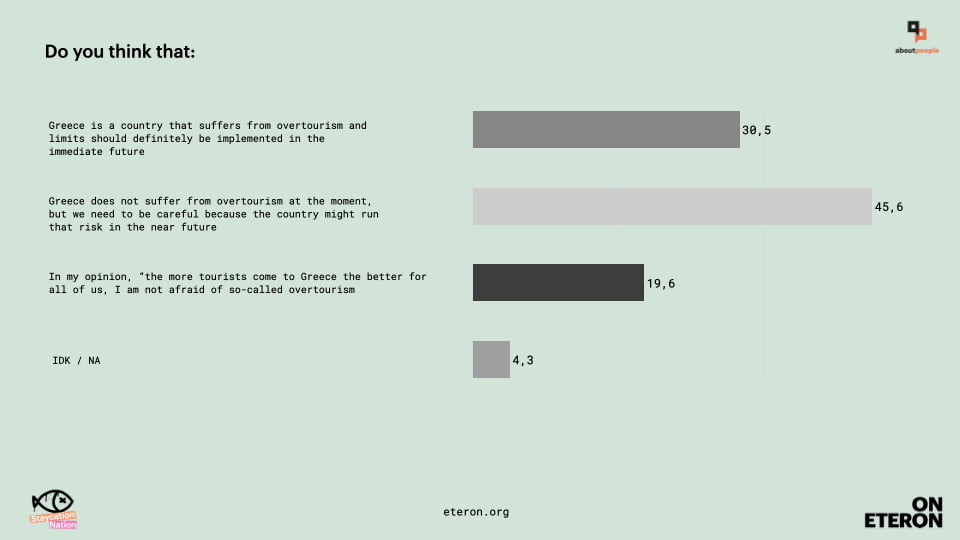

Regarding overtourism, 30.5% of Greeks believe that it is an already existing problem, while 45.6% believe that it is “not yet a problem”, although we need to stay vigilant because it could be a threat in the near future. Finally, only 19.6% state that, in their opinion, there is no such risk and believe that the more arrivals we have in Greece, the better.

Table 9: Assessment of the impact of tourism in Greece

From the above, it can be reasonably concluded that society feels a certain discontent with tourism to an extent that cannot be ignored. Of course, this discontent does not mean that there is actually a problem, and the breakdown of responses does not suggest that the intensity of this feeling is currently leading to a general contestation of the domestic economic model. However, as shown in Table 6, there are individual issues about which there is considerable dissatisfaction. So much so, in fact, that the majority of respondents are openly in favour of mobilisations.

But is there an overtourism problem or is there a risk of tourism becoming a problem? As illustrated in the table below, there is a significant imbalance in economic activity across the country. In the South Aegean, the Ionian Islands and Crete, tourism expenditure as a percentage of GDP reflects the high level of touristic activity. Therefore, if there is a problem, it is certainly more pronounced in some regions, which means that our survey sample is not big enough to be able to compare the responses we got with the data in Table 10. This imposes certain limitations on our conclusions, but at the same time, it also enriches the concerns emerging from the responses to the questionnaire, while indicating the areas into which social research is worth looking, in order to further our understanding of our object of study.

It is therefore difficult to speak of a generalised overtourism issue. Nevertheless, if we take into account the definition of the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO, 2018) according to which the phenomenon can be described as “the impact of tourism on a destination, or parts thereof, that excessively influences the perceived quality of life of citizens and / or the quality of visitors experiences negatively”, it becomes clearer that citizens are concerned about the consequences of mass tourism.

5. Conclusions

The present survey highlights the following contradiction: the negative impacts are increasingly perceived by residents, with 63.5% concerned about the environmental impact, while at the same time 82.4% recognise tourism’s economic contribution to the economy. Of course, some of its negative aspects are also becoming apparent, with the survey participants particularly highlighting the inflation in goods prices and rental costs. More specifically, 65.2% agree that tourism increases expensiveness and 78.7% believe it contributes to rent increases.

There is therefore a fatigue or wariness of the locals and of course a serious concern for Greece’s present and, even more so, its future. This phenomenon can only be countered by measures that will focus on a more equitable distribution of the economic benefits of tourism to the residents of the areas that are most under pressure, by increased investments in the infrastructure of those areas, and pronounced efforts to improve public spaces and protect local residents from “market failures”, as we’ve seen it happening sometimes with the long-term rental costs, as well as from many other possible negative externalities.

Failure to address the negative impact of mass tourism not only threatens the people’s quality of life, but also the touristic product itself. The residents’ negative views regarding overtourism can worsen their perception of one’s destination as a good place to live (GPL), which is something that in turn can affect the overall atmosphere and hospitality experienced by tourists and thereby indirectly reducing their level of satisfaction (García-Buades et al., 2022).

Bibliography/ References

Dwyer, L., Forsyth, P., & Dwyer, W. (2020). Tourism Economics and Policy.

García-Buades, M. E., García-Sastre, M. A., & Alemany-Hormaeche, M. (2022). Effects of overtourism, local government, and tourist behaviour on residents’ perceptions in Alcúdia (Majorca, Spain). Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 39, 100499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2021.100499

García-Hernández, M., de la Calle-Vaquero, M., & Yubero, C. (2017). Cultural heritage and urban tourism: Historic city centres under pressure. Sustainability, 9(8), 1346.

Ikkos, A., & Koutsos, S. (2024). The contribution of tourism to the Greek economy in 2023 (1st estimate – preliminary data). INSETE.

Seraphin, H., Sheeran, P., & Pilato, M. (2018). overtourism and the fall of Venice as a destination. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 9, 374-376.

Koens, K., Postma, A., & Papp, B. (2018). Is overtourism overused? Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context. Sustainability, 10(12), 4384.

Kuzma, S., Saccoccia, L., Chertock, M. (2023). 25 countries, housing one-quarter of the population, face extremely high water stress. World Resources Institute Retrieved from:. https://www.wri.org/insights/highest-water-stressed-countries

Liaggou, Ch. (2024, July 25). SOS plan for water scarcity on the islands. Kathimerini. https://www.kathimerini.gr/economy/563142823/schedio-sos-gia-ti-leipsydria-sta-nisia/

Milano, C., Novelli, M., & Cheer, J. M. (2019). Overtourism and degrowth: A social movement’s perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(12), 1857-1875.

Research Institute for Tourism (ITEP). (2022). Tourism Carrying Capacity in the Athens Region. ITEP.

UNTWO. (2018). Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals – Journey To 2030.