Love, Parties and Politics: Pride Stories in Contemporary Greece

In loving memory of Dimitris/ Dimitra from Skala Sykamias.

On 26th June 1969, the Police raided the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar at Greenwich Village in Manhattan, New York. The bar patrons responded to the police violence and so a chain of events started, which is nowadays known as the “Stonewall Riots” or the “Stonewall Uprising”. This particular day is seen as a historical turning point for the LGBT+ movement worldwide, even though this narrative has been disputed, since the 26th June 1969 wasn’t by any means the first instance of people rallying against discriminations due to their gender and sexual orientation, nor was this the first time that LGBT+ individuals responded to police violence 1. Still, Stonewall is registered in people’s collective memories as an iconic moment of the fight for LGBT+ rights and it signalled the beginning of Pride events in different parts of the world from the ‘70s to this day 2.

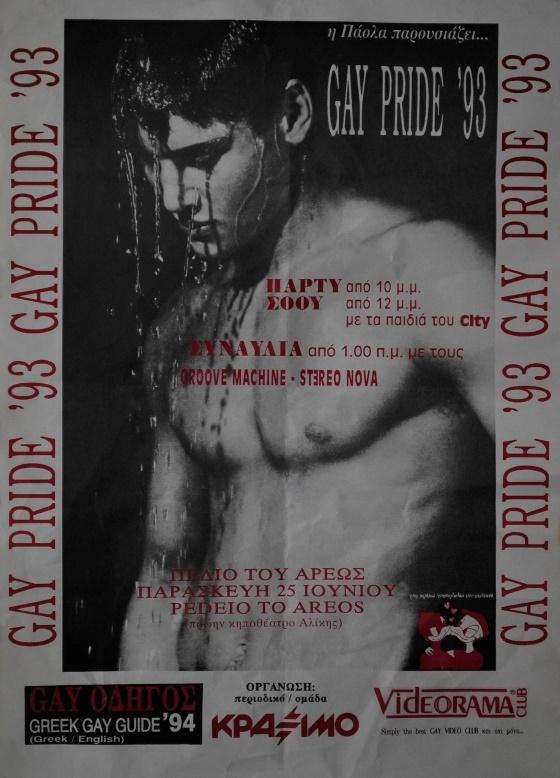

Source: Poster from the ’93 Gay Pride after Paolas’ calling. Published with Paola Revenioti’s permission.

In Greece, the air of democratisation and socio-political optimism that followed the fall of the Colonels’ dictatorial Regime in 1974, favoured the development of social movements, including the Homosexual Liberation Movement, as it was called during its early days. Looking back, the history of Pride events in Greece starts with gatherings organised by the Greek Homosexual Liberation Movement (AKOE in Greek) on the occasion of the “International Gay Pride Day” in 1980 and 1982, and by Paola Revenioti in the ‘90s, at Strefi Hill and at Pedion tou Areos. The first attempt to organise Pride gatherings in Thessaloniki was made by the Thessaloniki Homosexuals Initiative Group on 26th June 1991 3.

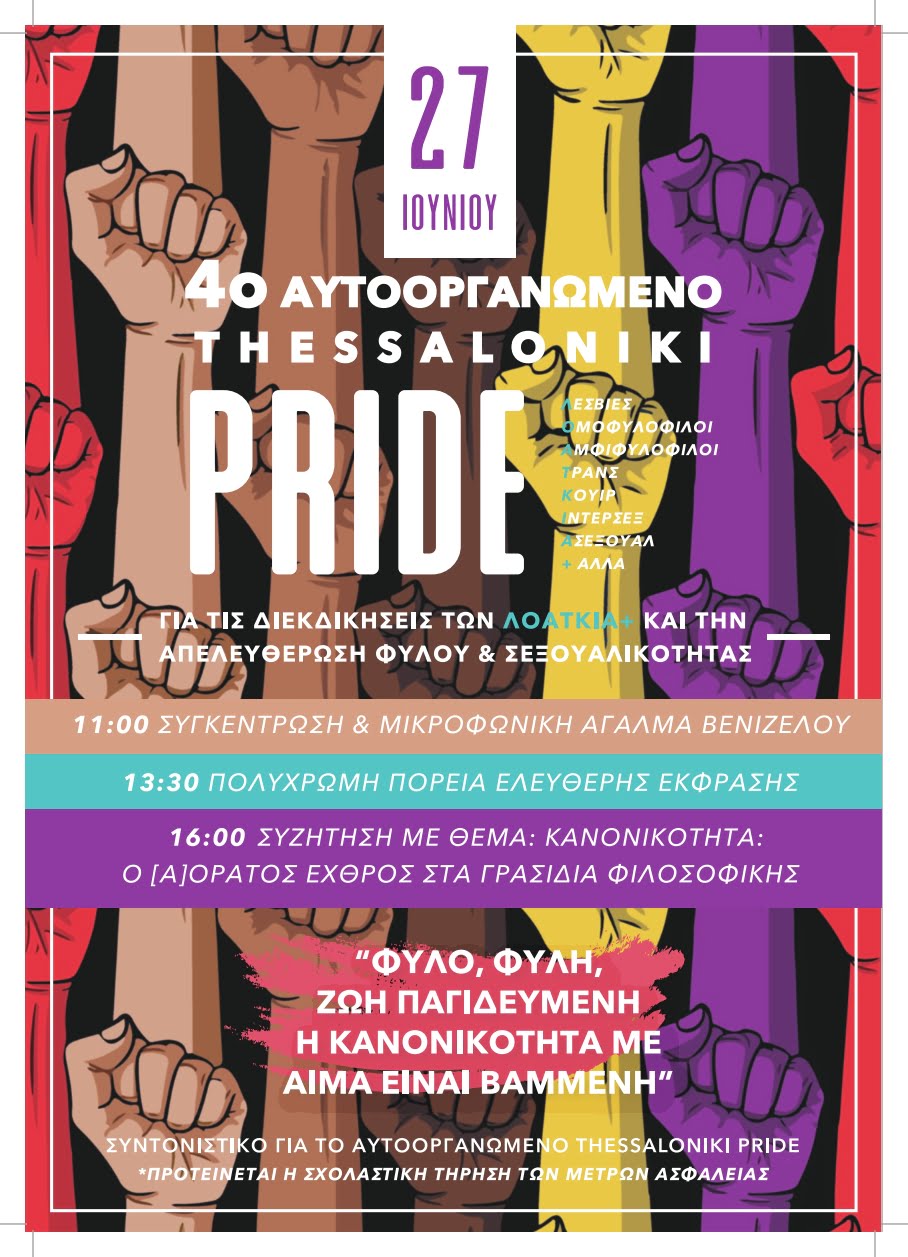

In 2005, the first Pride parade was organised in Athens. Since then, it’s been taking place every year with increased participation and gradually it’s gained more and more acceptance by a part of the political (party) spectrum that used to shun LGBT+ communities. In the spring of 2012, an organising committee was formed for Pride in Thessaloniki and this summer it’s their ten year anniversary.4 Also, the first self-organised Pride in Thessaloniki took place in 2017 and it’s still happening to this day. The fact that the majority of the LGBTQI+ events take place almost exclusively in Athens and Thessaloniki should be seen as problematic, but at the same time, it is related to the concentration of the majority of the population in the country’s bigger cities and to the development of less risky lifestyles in the cities for people who don’t conform to the narrow margins of cis heteronormativity.

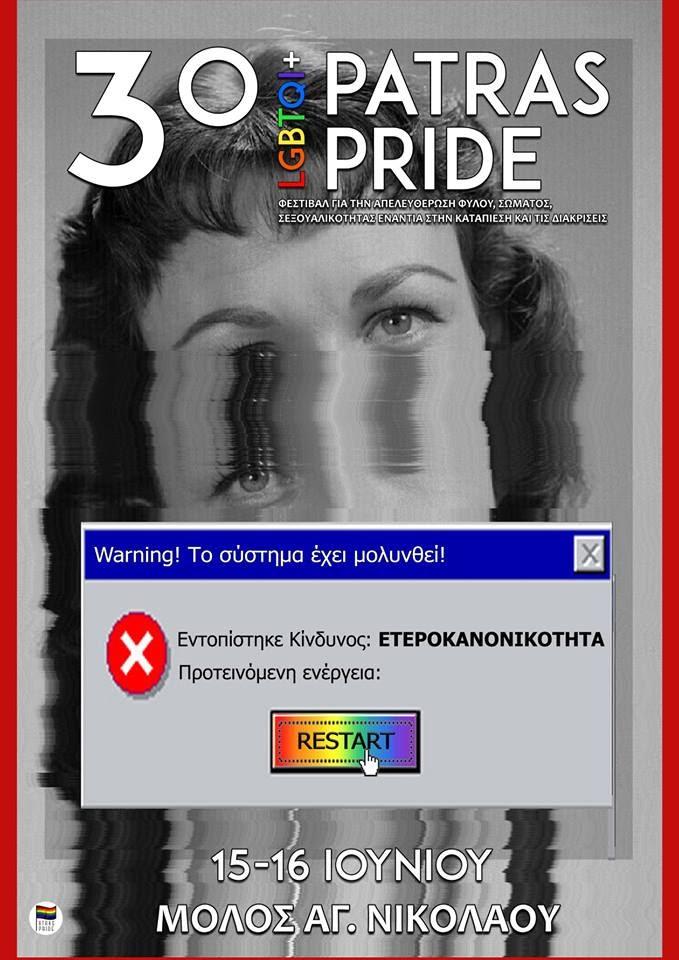

On 26th June 2015, in the town of Heraklion in Crete, the first “Visibility and Reclaiming Festival for the Liberation of Gender, Body, Sexuality: LGBTQI+ Pride Crete” was organised, and this particular event took place for three years in total. In the second press release they issued in 2015, the organisers stated that “The Festival will happen and that’s a fact. Anything else would mean that we’re denying our own existence. Our foundations are solidarity and self-organisation. We’re fulfilling our vision without sponsorships or corporate funding, thanks to the support of solidary groups and individuals, through diverse fundraising events.”5 In 2018, things shifted in Crete and the Her(aklion) Pride hosted the Self-organised Gender, Body and Sexuality Festival – an event that takes place every year to this day. In the Peloponnese, Patras Pride started in 2016 and initiated various discussions regarding sexwork, gender-based violence in the working space, same-sex parenthood, the marginalisation of LGBTQI+ people over 50 yo etc. and their events always include dj sets and drag shows.

The institutional turn that various LGBT+ organisations took after the ‘90s and the gradual transformation of some of them into NGOs, led to the depoliticisation of certain LGBT+ demands as well as to the commercialisation of LGBT+ identities and lifestyle. Two of the most important criticisms regarding mass Pride events concern corporate sponsorships that reproduce pinkwashing practices and the participation of the police during the parade/ demonstrations. In 2017, the “Initiative for a Self-organised Pride of Needs and Desires” did an intervention against the participation of a bloc called “Police Action Against Racism” in Athens Pride.6 The issue of the presence of uniformed policemen and women in Pride events has caused turmoil amongst organisations and committees in various countries (Holmes 2021, Nevius 2018), since the very existence of Pride Parades started as a response to police violence and oppression against trans, gay, lesbian and other LGBTQI+ individuals. Especially after the recent verdict in the Zackie Oh!/ Zak Kostopoulos’ case, where the policemen involved were acquitted thus “sending chilling signs of impunity” (according to Amnesty International’s statement on the case, 2022), the matter will most likely divide LGBTQI+ individuals and Pride committees in Greece even more in the coming years.

Source: 3rd Self-Organized Patras Pride 2018

A connection between the cross-thematic feminist demands and those of the LGBTQI+ individuals are not – nor have they ever been – something that we should take for granted. Very often in the past, Pride events were focused on the white male gay identity of toned and handsome Western men. Activist Evangelia Vlami, a spokesperson for Lesb. Equal (Lesbians for Equality) was one to constantly remind us that “The term is double, there’s homophobia and lesbophobia. There’s a gender dimension present in those phobias. Many women who happen to be lesbians, bisexuals or transexuals have to face discrimination because they’re women and also because they’re lesbians etc” (Kounadi & Georgiakodi 2012). Similar concerns regarding the Pride Parades’ cross-thematic approach were raised on the occasion of KEELPNO’s (Directorate of Epidemiological Surveillance and Intervention for Infectious Diseases) participation in Athens Pride in 2015,7 after the Minister for Health and Social Solidarity at the time, Andreas Loverdos, publicly shamed seropositive women.

By participating in Pride, we become a part of its history; shame is transformed into pride and our fights and struggles are like a big celebration, thus cancelling the false dipole that says that this should either be a colourful party or a political demonstration. The pandemic may have added obstacles in the organisation of Pride events (EuroPride 2020 which was scheduled to take place in Thessaloniki had to be cancelled) but still, it seems like we’re back at a stage where we can start planning future Pride events across the world. We still need visibility and empowerment, even if we have to look towards other directions for more diverse representations for trans, non-binary people and sexworkers, find bridges to connect to the black and the disabled comminities, fight side by side in the class struggle and show solidarity to refugees.

Everything that’s happening now is the result of copious struggle but we still have plenty of reasons to claim space for our lives, bodies and desires. Self-organised Pride events encourage the showcasing of more “difficult” and unpopular conversations, thus covering the gaps created by the mass events and strengthening the tendency to decentralise political actions away from the bigger cities, shedding light to solidarity networks that exist in different parts of Greece. Athens Pride in 2019 was dedicated to Zak and the self-organised Thessaloniki Pride in 2021, to Dimitra of Lesvos. Let us keep their memory alive and may our thoughts of those members of our community who were cruelly treated or assassinated become the engine that will drive us to more struggle, empowerment, pride and a better life.

*I would like to thank Irini Petropoulou for the valuable thoughts and information that she shared with me, and Paola Revenioti for giving me permission to include her poster from the Pride gathering she organised at Pedion tou Areos.

Bibliography

- Amnesty International. “ Greece: Letting police officers involved in brutal death of LGBTI activist off the hook sends chilling sign of impunity”, (2022)

- Armstrong, E.A., & Crage, S.M. “Movements and Memory: The Making of the Stonewall Myth” in American Sociological Review (2006), 71, 724 – 751.

- D’Emilio, John. Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1983), 1940–1970.

- Holmes A. “Marching with Pride? Debates on Uniformed Police Participating in Vancouver’s LGBTQ Pride Parade” in Journal of homosexuality (2021), 68(8), 1320–1352.

- Kounadi, Iro & Georgiakodi, Nicolas. “Homophobia: Stories from the crypt”, (2012)

- Mais, Christos (2015), “The Greek Homosexual Liberation Movement (AKOE): Gender resistance in Post-war Greece”, Entropia magazine, issue 5.

- Batsioulas, Aris (2019). “20th Century Boy” in Invisible History: LGBTQI+ course, experiences and policies in Greece, edited by D. Aggelidis, N. Papathanasiou, E. O. Christidi. Athens: Efimerida ton Syntakton.

- Nevius, Delaney, THE FIRST PRIDE WAS A RIOT: How Queer Activism Has Partnered with Police to Hurt the Community’s Most Vulnerable, (29 Hastings Women’s L.J.,2018), 125

- Stryker, Susan & Jim Van Buskirk. Gay by the Bay: A History of Queer Culture in the San Francisco Bay Area (San Francisco, CA: Chronicle, 1996)

- Stryker, Suzan. “Anatomy of a Riot: The Role of the 1966 Compton’s Cafeteria Disturbance in the Politicization of San Francisco’s Transgender 748—–AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW Community.” Presented at the American Historical Society Association Annual Meeting, January 5, San Francisco, CA. (2002)

Footnotes

- D’Emilio 1983, Stryker & Buskirk 1996, Stryker 2002[↩]

- Armstrong & Crage 2006[↩]

- Basioulas 2019:5[↩]

- https://thessalonikipride.com/to-thessaloniki-pride[↩]

- http://cretepride.blogspot.com/2015[↩]

- https://selforganizedprideinathens.wordpress.com/2017/06/13/anakoinosi-sxetika-me-tin-paremvasi-sto-athens-pride/[↩]

- transgendersupportassociation.wordpress.com/2015/06/02[↩]